“And the $64 question is ….”

May 5, 2019

JAMES HOLZHAUER/ABC photo

I have never watched Jeopardy, and consequently I have no vested interest in how James Holzhauer has run up his record-setting winning streak. I can’t help knowing, however, that there is a kerfuffle over it in which some critics say Holzhauer is ruining the game for others. If I understand the complaint correctly, the issue is that Holzhauer’s success has as much to do with his mastery of the buzzer as it has to do with the breadth of his knowledge. Considering other moral and ethical issues confronting the Republic at the moment, I’m not sure now much urgency to assign to this one.

Dr. JOYCE BROTHERS/Denver Post

The dust-up did remind me, though, of Dr. Joyce Brothers, the psychologist, who was known for the bulk of her career as a television personality and author but who first burst into the public’s consciousness as a contestant on The $64,000 Question. Several of the contestants on that show become instant celebrities. In Joyce Brothers’ case, the immediate interest was in the fact that this young woman was presenting herself as an expert on boxing. I have read that the producers recommended that topic to her, but I don’t know if that is true.

Dr. Brothers decided to seek a spot on the show in 1955 in order to shore up her family’s finances while she was caring for her daughter and her husband, Milton, was in a low-paying medical residency. She had quit teaching positions at Columbia University and Hunter College in order to stay home with her child.

HAL MARCH/Host of “The 64,000 Question”/TV Guide

Whether she or the producers chose the topic, Dr. Brothers was not historically a boxing aficionado. Apparently a person with a strong will and outstanding capacities for concentration and retention, she memorized dozens of reference books on boxing. As a result, she won the top prize. Two years later, she won the top prize on The $64,000 Challenge in which she was pitted against seven experts on the prize ring.

The $64,000 Question was later mired in scandal as it was revealed that some of the contestants had been fed answers in advance, but Dr. Brothers was not implicated in any such scheme. In fact, it has been reported that the producers tried to derail her progress by throwing obscure questions at her, but she answered them correctly.

Whether Dr. Brothers’ approach was any less in the spirit of the show than Holzhauer’s, I’ll leave to minds more acute than my own.

PHIL BAKER

Meanwhile, the name of The $64,000 Question obviously derives from the idiomatic expression “The $64 question,” meaning the most important or perplexing question in a given situation. The idiom itself originated on a radio show of the 1940s, Take It or Leave It, on which the top prize was $64—about $925 today—which a person won by answering “the $64 question.” The big prize was paid in 64 silver dollars.

Time magazine reported at the time as follows:

“Take It or Leave It gives each of five people from the studio audience a chance to answer seven questions correctly (or quit with a cash prize after any number of correct answers less than seven). Seven correct answers in a row nets the maximum $64.”

Members of the studio audience would encourage or heckle the contestants with each decision to take the money and run or move on to the next level.

The host of the show was a comic actor named Phil Baker. Time, reporting in 1944, gave this account of an incident that reflects the character of the show:

“The program pays out about $250 a week, mostly to servicemen on leave and other citizens who can use the money. Men are much more apt to shoot the $64 works than women. Men are also more apt to get Phil Baker in the kind of trouble he encountered recently when a sailor, asked to give the navy definition of ‘noise,’ gave not ‘celery,” which was right, but ‘Boston beans.” Baker gave the sailor $64 and told him to get back to his ship.”

Apparently, the producers of Take It or Leave It didn’t have to worry about ringers.

Sic transit and so forth

March 31, 2019

When I saw this display at the supermarket today, it sent my mind reeling back to an eposide of Downton Abbey in which the Australian soprano Nellie Melba was engaged to gave a recital at the Granthams’ mansion. More precisely, this display reminded me that among the historical inaccuracies presented in that series, the visit by Nellie Melba was one of the most glaring—to anachronisms such as I am, at least.

One feature of the episode was that Charles Carson, the Granthams’ head butler, was scandalized that a mere entertainer would be invited into the house. According to the Downton Abbey storyline, Carson had been a song-and-dance man before he took on the pompous persona of a butler, but apparently he didn’t see the irony in that.

NELLIE MELBA/Lilydale Historical Society

Carson treated Melba—portrayed by past-her-prime soprano Dame Kiri Te Kanawa—as though she were a hired hand, leaving her in her room with nothing but a cup of tea. Others in the house made caustic remarks about having to sit through her performance.

Actually, by 1922, when this was supposed to have occurred, Nellie Melba was a dame commander of the Order of the British Empire for her charity work during World War I. More to it, she was one of the most celebrated singers in the world, eagerly received by royalty.

As Robert Christiansen, the opera critic for The Telegraph pointed out when the episode was first broadcast, Nellie Melba “would only have sung at a private party as a personal favour to her host. Melba was nobody’s hireling: she called all the shots, and the Granthams and their staff would have quaked at her approach.”

A story by Tom Huizenga of National Public Radio included this passage:

“Even today, Melba’s recorded voice rings clearly as a favorite of Tim Page, Pulitzer winner for criticism and professor of music and journalism at USC.

“‘There’s something sort of unreal about it,’ Page says. ‘It’s a voice of ethereal purity with perhaps the only perfect trill I’ve ever heard.’ Another celebrated Melba attribute is accuracy: ‘She hit things absolutely on pitch,’ he continues. ‘You never hear Melba sliding into a note. Her tone was as reliable as a keyed instrument. She’s just dead on.'”

Incidentally, while Melba—whose birth name was Helen Porter Mitchell—has been forgotten by all but opera buffs, her professional name lives on in the product you see above, which was named after her, as was peach melba and several other delicacies.

You can hear Nellie Melba with Enrico Caruso in the duet “O Soave Fanciulla” from Giacomo Puccini’s La Boheme by clicking HERE.

Moonlight on the Wabash

June 2, 2018

David Lindquist, writing in the Indianapolis Star, recently took note of the end of the television series The Middle by recalling 20 fictional characters that, as Lindquist wrote, “put Indiana on the map.”

I’m pretty sure that Indiana, which I understand has been populated since around 8,000 years before the birth of Jesus, has been “on the map” at least since 1800 when Congress defined the Indiana Territory, which included what is now the sovereign state, so to speak.

Johnny Gruelle

Anyway, the characters that Lindquist cites for reminding us of Indiana in more recent times included James Whitcomb Riley’s “Little Orphant Annie” who was from Greenfield; M*A*S*H surgeon Frank Burns, who was from Fort Wayne; and Woody Boyd of Cheers, who was from Hanover.

And Linquist’s Hall of Indiana Fame included Raggedy Ann and Andy, who were created by former Indianapolis Star cartoonist Johnny Gruelle who featured them in a series of children’s books that he wrote and illustrated. Gruelle made the first Raggedy Ann doll in 1915 and published the first book, Raggedy Ann Stories, in 1918, and the second, Raggedy Andy Stories, in 1920. Ann and Andy were siblings. I suppose they still are. For a time, the dolls and the books were sold together.

My personal Ann and Andy, circa 1968

Although there are alternative versions of the origin of Raggedy Ann, it appears that was planted in Gruelle’s mind when he found a homemade rag doll in the attack of his parents’ home in Indianapolis and mused that the doll could be the subject of a story. After his daughter, Marcella, was born, and Gruelle observed her playing with dolls, he was inspired to write what became the Raggedy Ann stories.

It is not true, as is often reported, that his daughter found the doll in the attic; nor is it true that Gruelle created Raggedy Ann as a tribute to Marcella after she died, at the age of 13, as a result of a contaminated injection. Anti-vaccination interests have adopted Raggedy Ann as a symbol, based on the latter myth, but Marcella’s death was attributable to the contamination, not to the vaccination itself.

Mug purchased by my parents circa 1941

As for the name of the doll, it is notable that Gruelle’s father, Richard, an artist, was a friend of James Whitcomb Riley, whose poems included “The Raggedy Man” and “Little Orphant Annie”—though why “orphant” rather than “orphan” I am not aware.

Gruelle’s inspiration after finding the forgotten doll has lived on in many forms besides the books, including animated films, a television series, a comic book, a stage play, and a Broadway musical.

Johnny Gruelle was an exceptional talent whose work appeared in the Star as well as the Toledo News-Bee, the Pittsburgh Press, the Tacoma times, and the Spokane Press. In 1911, he and about 1500 other aspirants entered a cartooning contest sponsored by the New York Herald, and Gruelle won with a creation he called Mr. Twee Deedle. The strip ran in the Herald for several years. Not too raggedy at that.

Star as well as the Toledo News-Bee, the Pittsburgh Press, the Tacoma times, and the Spokane Press. In 1911, he and about 1500 other aspirants entered a cartooning contest sponsored by the New York Herald, and Gruelle won with a creation he called Mr. Twee Deedle. The strip ran in the Herald for several years. Not too raggedy at that.

You can read a lot about the history of Raggedy Ann and Andy by clicking HERE.

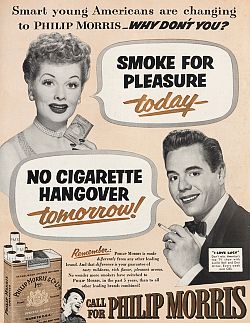

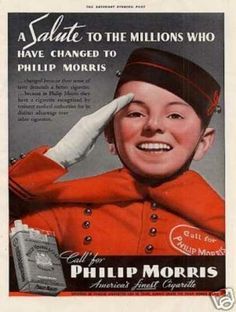

Smoke if ya got ’em

July 23, 2016

Madonna, Beyonce, Cher, Adele, Prince, Sting, Bono, Liberace.

Madonna, Beyonce, Cher, Adele, Prince, Sting, Bono, Liberace.

Johnny Roventini?

Using only one name has been an effective marketing device for a lot of entertainers, and for none more effectively than for Johnny. When I was a young boy, my mother told me that my father had been at some public event the previous night, and that had met Johnny. She didn’t have to say his last name—none of us knew his last name; I knew immediately that she meant the diminutive bellboy who pitched Phillip Morris cigarettes.

On radio, on television, in print ads, and in public appearances, Johnny was one of the most familiar figures of his time, with his snappy uniform, his tray with the written message on it, and his high pitched announcement: “Call … for … Phillip Mahr-rayss.” That’s how he pronounced it, as you can hear at the beginning of this Lucy and Desi ad.

Johnny, who was born in Brooklyn in 1910, was forty-seven inches tall as an adult and weighed about 59 pounds. He was employed in the 1930s as a bellboy at the New Yorker Hotel in Manhattan in an era when hotel lobbies were elaborate gathering places. Uniformed bellboys were fixtures in these spaces, often calling out the names of persons for whom there were inquiries or telephone or written messages. The New Yorker used Johnny’s size as a promotional gimmick.

Johnny came to the attention of Milton Blow, whose advertising agency had the Phillip Morris account. Blow brought a Phillip Morris executive to the lobby to watch Johnny in action and, according to Roventini, asked Johnny to page “Phillip Morris.” If that story is true, no one answered the page, but the impromptu audition launched the young man into what turned out to be a lucrative, forty-year career as the public image of the Phillip Morris brand. He also became one of the most recognizable celebrities of his time and was welcome in the company of everyone from Marlene Dietrich to Dwight Eisenhower.

Johnny Roventini’s fame was advanced significantly when Phillip Morris agreed in 1951 to sponsor the television series I Love Lucy, a show that was shunned by advertisers who in those times were afraid of the public reaction to a marriage between a Cuban man and an American woman. Roventini became personally attached to Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, and he and the sponsor stood by Ball after news reports that the House Un-American Activities Committee was investigating charges that Ball had Communist connections.

I have never smoked a cigarette, but I grew up in an era in which smoking and cigarette advertising were pervasive. People of my age will remember the campaigns—”LSMFT” (“Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco”), “Pall Mall (pronounced ‘pell mell’). Outstanding—and they are mild!” And the campaign that drove English teachers to distraction, “Winston tastes good, like a cigarette should.” But no tobacco campaign had Johnny’s personality.

After public awareness of the lethal effects of smoking led to a federal ban on broadcast cigarette advertising in 1970, Johnny continued to make public appearances on behalf of the brand until 1974. He died in 1988.

“Oh, bother!”

April 3, 2015

When a young new colleague arrived at my workplace, his name caught my attention. His first name is Sterling. He is the second person of that name that I’ve worked with, but the first instance goes back at least 35 years. Sterling is not a name I associate with men in their twenties. However, I checked on a web site that tracks the frequency of male names, and I found that Sterling has been making a comeback. Its popularity peaked in the 1890s when it ranked 388th out of 1,000 boys’ names. It went into a steady decline after that until the 1960s, when it ranked 497th. Then it had a resurgence and was 512th in the 1980s. Then there was a precipitous drop to 872nd place by 2008, and then a very sharp revival that carried it to 684th place in 2012 — the last year for which figures are available. To put these rankings in real terms, when the name Sterling was at its peak of popularity just before the turn of the 20th century, it was pinned on about 122 of every million babies born.

There were two well-known actors named Sterling. One was Sterling Hayden whose career stretched from 1941 to 1982. My new co-worker’s full name is very similar to that of the second actor, Sterling Holloway. He was named after his father, Sterling Price Holloway, who ran a grocery store in Cedartown, in northwestern Georgia, and served as mayor there in 1912. He in turn was named after Sterling Price, a lawyer and slave-holding tobacco planter in Missouri. He served as governor of the state from 1853 to 1857 and as a member of Congress. Price was a brigadier general in the U.S. Army during the Mexican War and a Confederate Army major general during the Civil War. I gather he was much more successful in the first war than in the latter. After the Civil War, he led his troops into Mexico and was rebuffed when he tried to enlist in the service of the colonial Emperor Maximillian. That episode inspired the 1969 movie “The Undefeated” which starred John Wayne and Rock Hudson. But I digress.

I first became aware of Sterling Holloway when he had a recurring role as Waldo Binney, the next-door neighbor to Chester A. Riley and his family in the television series “The Life of Riley.” Holloway had an odd voice and an unconventional appearance, and Waldo Binney was a quirky character, so he quickly became a favorite of mine. I didn’t know when he appeared in “The Life of Riley” in 1953-1956 that he had been a professional actor since 1926, when he appeared in a silent film called “The Battling Kangaroo.” He eventually performed either on screen or as a voice actor in at least 177 film and television properties as well as commercials, stage productions, radio shows, and recordings. In 1975 he shared a Grammy Award for the best recording for children, “Winnie-the-Pooh and Tigger Too.” Working for Walt Disney Studios, he lent his high-pitched voice to Mr. Stork in “Dumbo,” Adult Flower in “Bambi,” the Cheshire Cat in “Alice in Wonderland,” Kaa in “The Jungle Book,” Roquefort in “The Aristocats,” and Winnie-the-Pooh in several films, TV shows, and recordings.

GEORGE REEVES and STERLING HOLLOWAY in an episode of the TV series “The Amazing Adventures of Superman.”

Holloway’s off-beat voice lent itself very well to certain kinds of songs, and he introduced two standards — “I’ll Take Manhattan” and “Mountain Greenery” — while he was appearing on Broadway in “Garrick Gaieties,” a revue by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, in 1925 and 1926. You can see Holloway’s touching performance of the song “The End of a Perfect Day” in the 1940 film “Remember the Night” by clicking HERE. The song was written in 1909 by Carrie Jacobs-Bond. I understand NBC owns the rights to this film.

You can hear Holloway’s voice-over in a Peter Pan Peanut Butter commercial from the 1950s by clicking HERE.

Joe Franklin, sui generis!

January 25, 2015

Joe Franklin, who died yesterday, once did a live show at Menlo Park Mall in Edison, here in New Jersey, and a colleague of mine went to cover it. He came back with several anecdotes that confirmed the impression we already had of this unique personality who had been a fixture on New York radio and television for decades. For example, my colleague related that after the show a young man introduced himself to Franklin and explained that he was trying to get started in a career as a comedian. Without taking a second to think, Franklin said, “Meet me on the northwest corner of Times Square and Forty-second street at ten o’clock Monday morning. I’ll make you very happy.” And he made the young man happy by taking him to the WOR-TV studio and putting him on that day’s talk show.

When my colleague’s story had been published, he decided to go to Manhattan in person to deliver copies to Franklin. I accepted the invitation to go along. When we arrived at the studio, Franklin was in the last quarter-hour of his show. Once the broadcast was over, we approached Franklin, and my colleague introduced me and turned over the tear sheets. Franklin grinned and, without missing a beat, said, “Why don’t you guys come on the show?” Mind you, he had never seen me or, for that matter, heard of me before. “What would we talk about?” I asked him. “You can co-host the show, interview the guests.” And so we did.

Sometime after that, my colleague and I were discussing Joe Franklin with others in the newsroom, and I said, “I’ll bet that if we called him up and asked if we could come on the show again, he’d say yes.” My colleague decided to test that theory. He said he wasn’t sure Joe remembered him, but the sentence was hardly spoken before Joe blurted out a date, and we went on again.

We had no illusions about any of this. Joe wasn’t Dave Letterman. It was probably a constant challenge for him to fill his dance card. Still, he had a lot of friends and he often scored a guest with somewhat more status than we had. In fact, on one of the shows we were on, one of the guests was Charles Hamilton, who was one of the best-known handwriting experts and autograph dealers of his time. He had debunked the so-called Hitler Diaries in 1983. But even when his guests were from the middle of the pack, Joe had a genius for appearing enthusiastic. He probably made a lot of folks feel good about their careers despite evidence to the contrary.

He was a combination of pitchman, raconteur, purveyor of nostalgia, and carnival barker, and he was quintessential New York. He ought to be out there on the square in bronze, hanging out with Father Duffy and Georgie Cohan.

I have spent time with a lot of celebrities in the past five decades. Few were more memorable than Joe Franklin.

“That Trixie’s a sweet kid” — Ralph Kramden

November 6, 2014

When Joyce Randolph marked her 90th birthday recently, I took a glance at the Wikipedia article about her to see how recently it had been updated. Among the things I read there was that she was recruited to play Trixie Norton in Jackie Gleason’s series The Honeymooners after Gleason saw her doing a commercial for Clorets, which was a chlorophyl gum on the order of Chicklets. That isn’t what she told me when I visited her at her Central Park West apartment in 1976. On that occasion, she said that she had first been hired by Gleason to appear in a serious sketch he insisted on performing on his comedy-variety show, The Cavalcade of Stars, which was then being broadcast on the Dumont Network, originating at WABD, Channel 5, in New York.

“Gleason liked to write for the show or suggest things to the writers,” Joyce told me. “This time he wanted to do a serious sketch about a down-in-the-heels vaudevillian who meets a woman he loved many years before. We did very little rehearsing, and when we went on with it people were a little flabbergasted. They didn’t know whether to laugh or cry or what. A couple of weeks later, the part of Trixie came up, and Gleason said, ‘Get me that serious actress.’ ” Perhaps the Clorets commercial got her cast in the dramatic turn, but however Joyce got cast as Trixie Norton, she became an immortal among television actors. The Honeymooners first appeared in October 1951 as a six-minute sketch on The Cavalcade of Stars. The sketch became one of the regular features on the show; Trixie Norton was introduced as a former burlesque dancer and was played, in only one episode, by Elaine Stritch before Joyce Randolph got the part. In later and less successful iterations of The Honeymooners Trixie was played by Jane Kean, but the part is universally associated with Joyce Randolph.

That is true, in part, because Joyce played the part when The Honeymooners was broadcast as a free-standing half-hour sitcom in 1955 and 1956. Those thirty-nine episodes are among the most revered examples of American television comedy. While many shows from that era — Our Miss Brooks and The Life of Riley, for instance — seem stilted in retrospect, The Honeymooners still entertains viewers who have seen the episodes over and over again. Joyce didn’t claim to know definitely why that should be so, but she speculated that one factor was the spontaneity of the performances. “We filmed a show once, and we did it with an audience,” she told me. “We’d start at 8 o’clock and we’d be finished by 8:30, just as though we did it live.” She said the cast would rehearse on Monday and Tuesday and film a show on Wednesday, then rehearse on Wednesday and Thursday and film a show on Friday.” Gleason himself frequently skipped rehearsals and missed cues and confused the lines during the filming, but there were no breaks or re-takes, so those mistakes were preserved as part of the shows. Joyce Randolph told me that in those early days of television, some audience members became so absorbed in the show that they lost their sense of what was real and what was not. “In fact,” she said, “people used to send in draperies and tablecloths for the set; they thought the Kramdens really lived like that.”

Joyce Randolph was kind of the Zeppo Marx in the Honeymooners act, because her own personality was not that distinctive (perhaps making her a perfect choice to play the wife of a New York City sewer worker) and she was playing fourth fiddle to three strong character actors — Gleason, Art Carney, and Audrey Meadows. Still, her own genuine earnest and wholesome quality came through in Trixie’s persona, which is why no one really could replace her in that part.

Don’t mess with Mr. Whipple

October 21, 2013

In a crossword puzzle I did recently, one of the answers was: “Don’t squeeze the Charmin.” This was a reference to what must have been one of the most successful series of television commercials ever produced. The centerpiece of these spots was the fictional supermarket manager Mr. Whipple, played by Dick Wilson, who was portrayed as catching customers squeezing the Charmin bathroom tissue because, of course, it was so soft. When he had a chance, Mr. Whipple, too, squeezed the rolls of paper. Who can resist that softness?

Dick Wilson played Mr. Whipple more than 500 times, beginning in 1964, and research showed that the commercials made the actor one of the most recognized people in the United States. And the expression itself, “Please don’t squeeze the Charmin,” could be heard echoing throughout the land. As marketing home runs go, this was a grand slam.

Although he was vigilant about the manhandling of Charmin, Mr. Whipple was presented as a mild-mannered fellow, but that’s a credit to Dick Wilson’s acting. He was no shrinking violet. He performed in more than 80 properties, including television series in which he appeared multiple times, including Get Smart, Sgt. Preston of the Yukon, M Squad, and The Lawless Years.

Wilson was born in Lancashire, England, to an Italian father and a British mother; his given name was Ricardo DiGuglielmo. Both of his parents were performers. The family moved to Canada where Wilson graduated from the Ontario College of Art & Design and began working in radio and vaudeville. During World War II, he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force. That seemingly bashful grocery man was among the fighter pilots who went head-to-head with the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain in 1940.

After the war, Wilson became an American citizen and, after working as a dancer in New York, moved to California and launched what turned out to be a long career. According to a story published in the Hamilton Spectator in Ontario, Wilson earned $300,000 annually for about twelve days of work on the Charmin commercials. Considering the impact he made, the bunch at Charmin no doubt considered it money well spent. But Wilson said the job was no snap. According to the same article, Wilson said doing commercials was “the hardest thing to do in the entire acting realm. You’ve got 24 seconds to introduce yourself, introduce the product, say something nice about it and get off gracefully.”

Dick Wilson died in 2007 at the age of 91. Click HERE to see him in a Charmin commercial in which he catches Teri Garr in flagrante.

“Oh, no, it isn’t the trees . . . .”

September 23, 2013

I was about to watch an episode of the Jack Benny Program recently when I became absorbed in the opening theme. The theme is associated not just with the television series but with Jack Benny himself. The song, “Love in Bloom,” was not written by amateurs. The music was by Ralph Rainger and the lyrics by Leo Robin. Ralph Rainger, a member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame, wrote a lot of music for movies between 1930 and 1942. One of his compositions, “Thanks for the Memory,” written for The Big Broadcast of 1938, won an Academy Award. (I’ll have more to say about that song in a later post.) Leo Robin, who wrote the lyrics to “Love in Bloom,” is also a member of the Hall of Fame. His work included “Thanks for the Memory,” “Beyond the Blue Horizon,” “Prisoner of Love,” and “Blue Hawaii.”

“Love in Bloom” was introduced in 1934 in the film She Loves Me Not. It was sung in a duet by Bing Crosby and Kitty Carlisle.

Crosby, that same year, was the first to record the song, which was nominated for an Academy Award.

Kitty Carlisle — an elegant woman whom, incidentally, I once visited at her Manhattan apartment — liked the song enough that she considered adopting it as her own theme. She scuttled that idea, however, when Benny made the song his signature, frequently playing it, and deliberately butchering it, on his violin.

The song has qualities that don’t come across in most of Benny’s renditions. You can see for yourself as Crosby and Kitty Carlisle sing it in the film. Click HERE.

You can also see a hiliarious routine in which Benny and Liberace play the song on the keyboard and violin on a 1969 episode of Liberace’s TV show. Here Benny lets himself show, for a while at least, that he was more competent on the violin than he cared to admit. Click HERE.

Netflix Update No. 80: “The Jack Benny Show”

August 22, 2013

My lack of interest in current television is at the point where I have a very limited diet. I’m not going to make an argument for the “golden age,” because I don’t think it’s valid. There have been many excellent shows since the 1950s. Still — and I’m willing to call this a matter of taste — I am attracted to early programming, and especially to situation comedies such as Make Room for Daddy, Burns and Allen, and the proto-sitcom, The Goldbergs.

Thank heaven, then, for services like Netflix, which makes many of these shows available, including The Jack Benny Show. Benny is a favorite of mine, not only because he was such a unique character and was so skillful in portraying his fictional persona — the miser who wouldn’t admit to being older than 39 — but because of his place in American show business history.

A poster advertises a broadcast of Jack Benny’s radio show on a station in Seattle. LSMFT, for the benefit of the younger crowd, stood for “Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco.”

The production values of television shows in the 1950s do not compare favorably with what we have become used to sixty years later, but the era got its “golden age” reputation because of the cadre of writers and performers who had migrated to television on a path that led from vaudeville, burlesque, and the legitimate theater by way of radio. Jack Benny and many of his contemporaries had worked very hard to develop their sense of what audiences at the time thought was funny or dramatic, and to develop the timing and delivery that would work in the new medium. They learned their lessons well; Jack Benny’s slow burn is still funny, even when you can see it coming from a mile away.

An interesting aspect of Benny’s show was his relationship with Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, a gravel-voiced black actor who was part of the Benny stock company which included, among others, announcer Don Wilson and Irish crooner Dennis Day.

Anderson who, like Benny, got his start in vaudeville, started working with Benny in radio in 1937, first in a few bit parts and then playing Benny’s valet. He played that role on radio and television until 1965. He was the first black performer to have a regular role on radio, but that meant that he was faced with what became a classic conundrum for black artists — the question of whether to play a subservient character or not work in movies, radio, or TV. It was a difficult question for the actors as well as for the black Americans who were being treated as second-class citizens if as citizens at all.

Given the racial climate at the time, The Jack Benny Show took an unusual approach by presenting Rochester as a quick-witted and sarcastic character who was always a little smarter than his boss. The approach was unusual also because this plot element juxtaposed two deadpan figures and the combination was hilarious and was sustained for nearly thirty years. At first, in radio, there was often a racial aspect to the humor surrounding Rochester, but after World War II, Benny — who took an unambiguous public stand in favor of racial harmony — insisted that all racial content be eliminated from his scripts.

Eddie Anderson was one of the most popular and highest-paid actors of his time. He appeared in many movies, including Green Pastures and Gone With the Wind. He handled his money wisely and was both wealthy and generous. Among other enterprises, he owned a company that manufactured parachutes for the American military during World War II.

You can see Jack Benny and Eddie Anderson in a typically funny scene by clicking here.