Play “Misty” for me

March 27, 2025

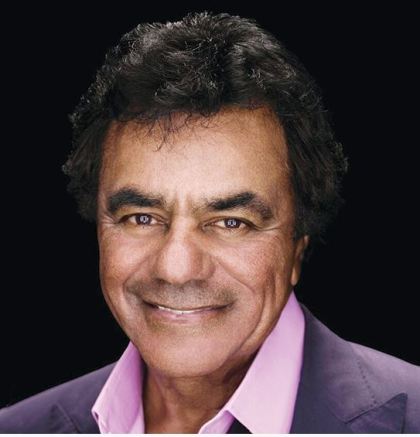

Bruce Klauber, a journalist, producer, and musician, last year quoted Barbra Streisand as saying, ““There are a number of good singers, a smaller handful of truly great singers, and then there’s Johnny Mathis.” Johnny Carson put it another way after a performance on the “Tonight Show” in which Mathis held the final note of “Pieces of Dreams” for about 30 seconds. “I guess,” Carson said, “that takes care of that song,” meaning, of course, that no one else needs to sing it. One could say that of so many songs that are identified with Mathis, and vice-versa, although his repertoire is so much larger in style and genre than the titles that first come to mind.

My wife, Pat, and I were wondering aloud just the other day how much longer Mathis would continue to tour, and today he answered us, and everyone else, by announcing his retirement. I’m not much younger than Mathis and still working full time, but I’m also at the age when death is no longer an abstract idea. An event such as Johnny Mathis retiring is one more tick of the clock that will not tick forever.

Mathis came into prominence in the mid 1950s, just in time for Pat and me to become fans, an affection we wouldn’t share until we started dating about eight years later. We danced to “The Twelfth of Never” at our wedding; that’s “our song” 61 years later. We have gone to several Mathis concerts including one at which he sang five songs during his encore–a suitable reward, I thought, for the folks who beat it for the exits when he finished his regular set.

I spent many years in the newspaper business covering or supervising coverage of local affairs including municipal and county government. I took advantage of the access that job gave me by developing a sideline interviewing people in entertainment and sports. On one occasion, which happened to be Pat’s birthday, I arranged to attend a “press availability” Mathis was subjecting himself to in advance of a concert here in New Jersey. Without telling her where we were going, I took Pat with me. We were ushered into a room where there were only two other reporters who, it turned out, didn’t seem to know anything about Mathis nor care to find out. They were mute.

Johnny Mathis came into the room, wearing a sweat shirt and a pair of torn jeans, and sat on the edge of a wooden table, and Pat engaged him in conversation. He agreed when she told him that at the beginning of his career he seemed uncomfortable on stage but that he had gradually developed a graceful presence. She asked him if he had ever considered dramatic acting, and he said that he had expressed that ambition but that no one would take him seriously. They went on like that for almost an hour as though they had forgotten that anyone else was in the room until, at one point, Mathis looked at me and said with a laugh, “My God! He’s writing this down!”

We once found on YouTube a long interview with Mathis in which the interviewer asked, in effect, “After making so many recordings over so many years, which ones do you like to listen to most?” “I don’t listen to my records,” Mathis said. “After sixty years, I’m tired of the sound of my own voice!” Well, we haven’t heard his voice as much as he has, but the passage of nearly seventy years now has done nothing to make it any less thrilling and soothing and mesmerizing. Johnny Mathis is retiring, but we have stacks of CDs and vinyls to keep him with us till the ticking stops.

You’re lookin’ swell, Dolly!

December 30, 2024

September 17, 1932

I use this photo as wallpaper on my computers, because it is one of the best baseball action shots I have ever seen. The play took place on September 17, 1932 at the Baker Bowl in Philadelphia. The airborne player is Dick Bartell of the Phillies. The catcher, waiting to make the tag, is Gabby Hartnett of the Cubs. His teammates, visible in the first-base dugout, seem rather nonchalant about the play, but not so the fans—consisting largely of men in suits—who are on their feet. This was the first game of a double header. In the fourth inning, with the Phillies ahead 6 to 1, Bartell was trying for an inside-the-park home run. He was out on the play, but the Phillies would win the game, 7 to 1, and drop the second game, 5 to 1.

Although this episode is all about Bartell and Hartnett, I have always been drawn to the umpire, the trim figure crouching behind the plate, his mask off, his eyes glued to the anticipated point of impact. This is Albert “Dolly” Stark, an innovative, complicated, and ultimately tragic member of baseball’s dramatis personae. One of Stark’s distinctions was that he was the first Jewish umpire in baseball’s modern era and perhaps only the second Jewish umpire since baseball’s beginnings. I don’t know how we can be certain of this, but Jacob Pike, who umpired in the National Association in 1875 , is said to have been the only Jewish arbiter before Stark.

Stark was born in 1897 on the lower East Side of Manhattan. When Stark was a youngster, his dad died, and his mother lost her eyesight. After a police officer found the boy sleeping on a city street, Stark was consigned for a while to a facility for homeless children. Later, in an attempt to earn money for himself and for his family, he played second base for semi-pro and minor league teams. He tried out with the Yankees and Senators, but at 115 pounds, he could not compete at that level. It was during his playing days that he picked up the nickname “Dolly,” a reference to Monroe “Dolly” Stark, a shortstop with the Cleveland Naps and Brooklyn Superbas. Despite the surname, the Dollys were not related.

Albert Stark first umpired at the University of Vermont in 1921. By 1927, he was umpiring in the Eastern League where he did well enough to earn a promotion to the National League. At the time, Stark was also coaching basketball at Dartmouth College and continued until 1936. It might seem to us only common sense that an umpire does not remain stationary on the field but moves around in order to get the best view of a play. However, this was not a common practice until Stark introduced it, shifting positions behind the plate and running alongside fielders and runners to get the best view of plays.

The enmity between players and umpires, if is a staple of baseball lore, and at times it weighed heavily on Stark. And yet, when the Sporting News conducted a poll among players in 1934, they voted Stark the most competent umpire in the National League. If there were an award for the best-dressed umpire, Stark might have won that one too. He was very conscious of his appearance and always impeccably attired on the field in those days when umpires were decked out in suits, dress shirts, and ties, In 1935, Stark became the only umpire before or since to be honored at a day of his own. The event was held at the Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan where National League president Ford Frick presented Stark with a new car that had been purchased with small donations from Stark’s many fans.

In spite of this adulation, Stark’s relationship with baseball was sometimes tumultuous. In 1928, for instance, he wanted to quit in the middle of the season, because he didn’t think he was doing his job well. Bill Klem, one of the great umpires of that period, talked him out of it. Then, after the 1929 season, Stark again thought of quitting, this time because of the tense and lonely nature of umpiring, but he did continue in the 1930 season.

In 1936, Stark quit umpiring because, he said, he wasn’t being paid enough. His salary at the time was $9,000 per season which, according to some sources, was the equivalent of more than $200,000 today. Stark told Ford Frick—by then, the commissioner of baseball—that he would like to stay in the game in a different role, such as business manager or scout, but he never found such an assignment. He resumed umpiring in 1937 but had to retire in 1940 because of a knee injury.

Stark found other outlets for his talents. Among other things, he started a line of women’s apparel—the “Dolly Stark Dress; in 1936, he and Bill Dyer were the first radio team broadcasting Phillies games on WCAU; and he was co-host of an early television sports program, Your Sports Special, on the CBS network in 1948 and 1949.

Stark had a troubled private life. He financially supported his mother and sister, and his sister, who was chronically unwell, took her own life. He married in 1952 but was divorced after four years. Stark died in New York City in 1968.

Beyond “the perfect fool”

July 20, 2019

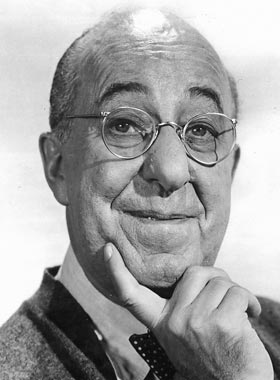

Ed Wynn, Jack Palance, and Keenan Wynn in Requiem for a Heavyweight

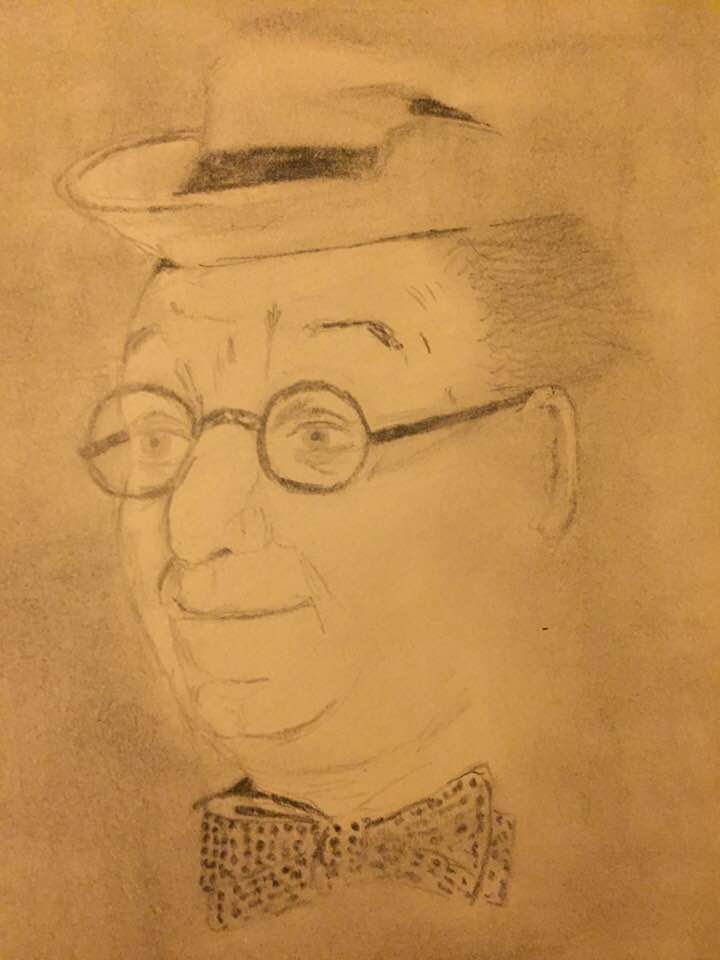

I recently came across a pencil drawing of Ed Wynn that I did about 50 years ago. Seeing that drawing was a prompt through which I discovered a pair of events in television broadcasting that combine for a unique and moving experience.

I’m old enough to be familiar with Ed Wynn, because he was frequently on television in the early days of the medium, days that coincided with my childhood. He usually appeared in the persona of “the perfect fool,” wearing a goofy outfit and doing a comedy schtick that made him a big star on the stage, in radio and television, and in film. I was also aware that he had appeared in a dramatic role in Requiem for a Heavyweight, which Rod Serling wrote for television.

ED WYNN

This is the story of a heavyweight boxer, “Mountain” McClintock, played here by Jack Palance, trying to cope with the end of his career in the ring. Ed Wynn’s son Keenan, a successful actor, also appeared in the production in a role closely associated with Ed Wynn’s character—Keenan playing Mache, the boxer’s manager, and Ed playing Army, the boxer’s trainer and cut man. The tension between these two men grows from Army’s conviction that Mache has no sense of Mountain’s humanity and basic decency. That was the first full-length drama broadcast live on television; it appeared on October 11, 1956, when I was 14 years old.

KEENAN WYNN

I don’t remember if I saw that broadcast, but because it was live, I hadn’t seen the performance since—that is, until now. After I came across that drawing of Ed Wynn, I read about his career. I learned that the rehearsals for Requiem for a Heavyweight were a painful experience for Keenan Wynn, because Ed Wynn couldn’t remember his lines or stage directions, and because he would frequently break into his silly laugh while rehearsing serious lines. The program had been promoted in part as the first joint appearance of the famous father and son, so replacing Ed Wynn in the role was problematic.

My drawing of Ed Wynn as “The Perfect Fool”

Ed Wynn seemed lost in the production, even in the dress rehearsal, but when the drama was broadcast on live television, his performance was not only flawless, it was so powerful that it led to several other important dramatic roles for him. In fact, he was nominated for an Oscar for his 1959 performance in The Diary of Anne Frank.

The broadcast of Requiem for a Heavyweight has been preserved; you can watch it by clicking HERE. You’ll notice problems with lighting, sound, and camera angles, but if you pay close attention to Ed Wynn, you’ll see the result of six decades of performing—comedy or not.

But wait. I also learned for the first time of a 1960 Desilu production called The Man in the Funny Suit, which was directed by Ralph Nelson, who also directed the television version of Requiem for a Heavyweight and the motion picture adaptation in 1962, in which Jackie Gleason and Mickey Rooney played the roles originated by Keenan and Ed Wynn.

Keenan Wynn, Ralph Nelson, and Ed Wynn in The Man in the Funny Suit

The Man in the Funny Suit is a dramatization of the actual events involved in Ed Wynn’s performance in Requiem for a Heavyweight. The story portrays Keenan Wynn’s attempt to convince his father that the era of “the perfect fool” had passed, and the son’s embarrassment and frustration over the elder man’s seeming inability to master his first dramatic role. What’s remarkable about this production is that Ed and Keenan Wynn play themselves, a brave and honest decision that would have been out of the reach of lesser men. Also playing themselves are Rod Serling, former world boxing champion Max Rosenbloom, Ralph Nelson, and—in a straight role—Red Skelton. You can watch this program by clicking HERE.

Viewing these two productions—in their chronological order—is a rare opportunity to see inside the relationship between a famous father and son. I, for one, an grateful for the self-confidence and generosity of heart, on the part of both men, that made this possible.

Books: “Missing Her”

May 20, 2019

Michio Kaku and the late Stephen Hawking, a couple of spoilsports in my estimation, both have maintained that time travel to the past is impossible. Their conclusions throw cold water on an idea that has stirred the imaginations of writers, film-makers, and ordinary people from, you should pardon the expression, time immemorial.

Michio Kaku and the late Stephen Hawking, a couple of spoilsports in my estimation, both have maintained that time travel to the past is impossible. Their conclusions throw cold water on an idea that has stirred the imaginations of writers, film-makers, and ordinary people from, you should pardon the expression, time immemorial.

But J.L. Willow (it’s a nom de plume) isn’t deterred by theoretical physics, and so she has employed time travel to the past—her own original take on it—as the critical factor in her new novel, Missing Her.

This is the writer’s second novel, and she has just graduated from high school and is en route to the study of mechanical engineering. Her first novel was The Scavenger, a tale rooted in the New York City drug culture; I wrote about that book here last April, focusing on Willow’s talent as a story teller and her inventiveness in structuring the story she tells.

J.L. Willow

I’m impressed with the same things in Missing Her in which a teenaged girl, Eliza, vanishes after leaving a party alone, and her closest friend, Vanessa, is determined to find out what became of her. I don’t want to drop a spoiler here, so I’m going to rely on the description of the plot that appears in the promotional material:

“Months pass without a break in the case, until one day Vanessa wakes up . . . in Eliza’s mind. Even more disturbing, she discovers she’s woken up two days before Eliza goes missing. Vanessa has no choice but to relive her best friend’s memories leading up to the disappearance and discover the truth about what happened. . . . But is the past set in stone?”

That last question is a point on which Kaku and Hawking and others have based their conclusion that we can’t go back. If we visited the past, we might change the present, and, as Hawking pointed out in a PBS series, if you visited the past you would already be there!

The paradoxes involved in going back in time play a part in the story Willow weaves, a story in which the time traveler is not walking around in plain sight in her own persona, but rather is observing events from within the mind of another person, at times influencing the behavior of that person—acutely aware of the risks involved in altering events that have already occurred. If and when she does get to the point at which Eliza vanished, how will she be able to prevent it?

Willow creates a perplexing mystery, so much so that I was late for work one day, because I had to read one more chapter—and I still had to drive to my office wondering where this story was going.

Somewhere around here, I have two citations I received for stories I wrote in the first grade. I have no recollection of those stories, and, while I never mastered fiction writing, I have been a writer all my life.

In that respect, J.L Willow and I are two of a kind, and that’s why reading her first published works, and being captivated by them, is such an exciting experience for me.

You can view the book trailer by clicking HERE.

Doris Day: “The Thrill of It All”

May 13, 2019

DORIS DAY

If you ‘re looking for a way to do homage to Doris Day, who died today, I recommend The Thrill of It All, which she made in 1963. I’m not a fan of this genre, but this movie has been a favorite of ours since it appeared in theaters the year before we were married. The story is about Beverly Boyer, a perky wife and mother-of-two, who stumbles into a career as the spokesperson for a soap manufacturer.

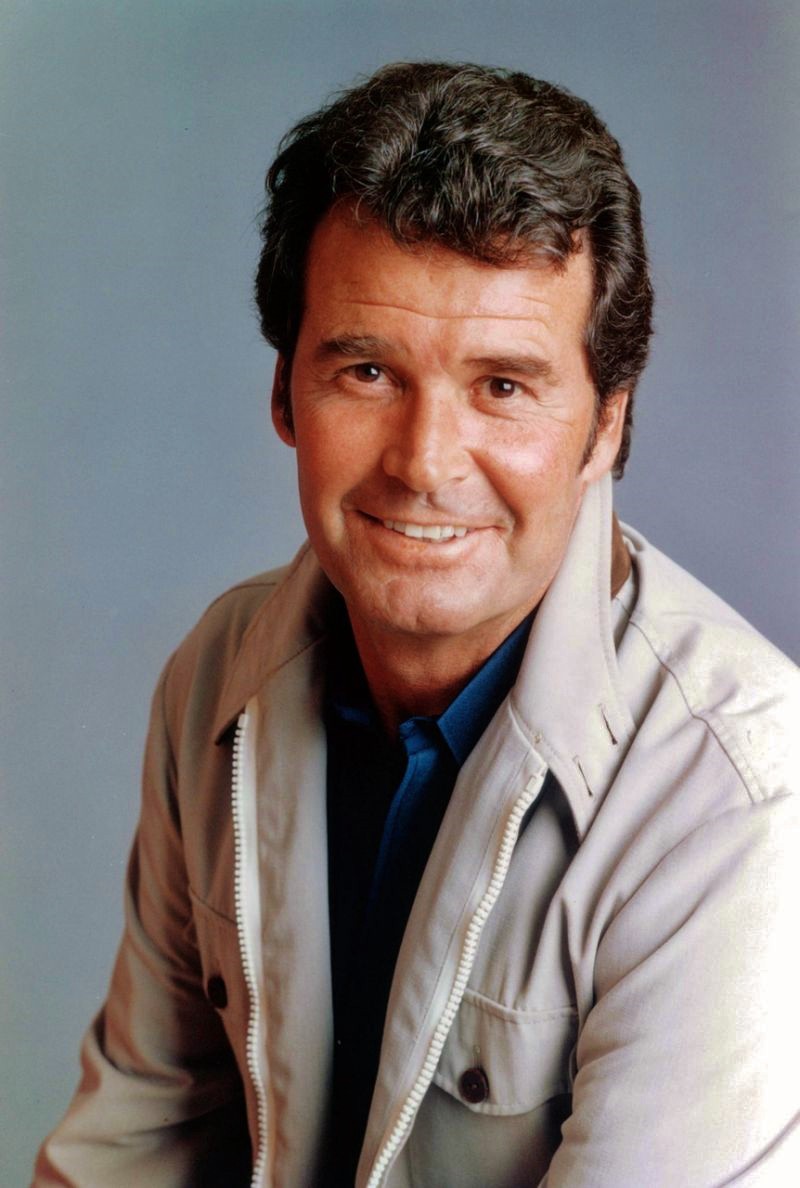

JAMES GARNER/NBC Universal

The fact that the principal product in this tale was called Happy Soap, will give you an idea of the tone of the movie. Beverly—played by Day, of course—makes a big salary from television commercials and becomes a celebrity, but the demands on her time play havoc with her marriage to Dr. Gerald Boyer, an obstetrician played by James Garner. And although I’m not crazy about slapstick, the scene in which Garner drives a Chevy convertible into a swimming pool tickles me every time I see it.

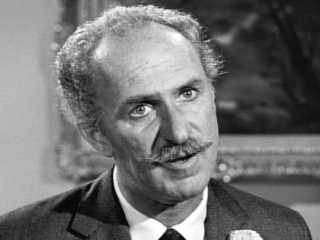

CARL REINER

I have read that Carl Reiner, the comedy genius who wrote this screenplay with another genius, Larry Gelbart, had wanted Judy Holliday in the female lead, but Holliday became ill with what proved to be terminal cancer. I have also read that Ross Hunter, one of the producers, wanted to invite Nelson Eddy and Jeanette McDonald to return to the screen in supporting roles, but they do not appear in the film.

EDWARD ANDREWS

As it turns out, the cast that did appear in this film was golden. The players included Arlene Francis, who was 56 at the time, as a patient of Garner’s character—a woman who is delighted to find herself pregnant well past the standard age for such an enterprise. Her equally delighted but frantic husband is played by Edward Andrews. I presume these were the roles Hunter had envisioned for Eddy and McDonald, but, with all due respect to those classic actors, no one could have played the parts for more laughs than did Francis and Andrews. In a scene in which the expectant couple gets stuck in city traffic when the birth is imminent, gives Andrews a chance to give the comic performance of his life.

The company also includes Reginald Owen, ZaSu Pitts, and Elliot Reid, and Reiner himself in some cameos.

I don’t know if most of the news reports of Doris Day’s death will adequately express the magnitude of her fame as a singer and movie actress. She was publicly recognized for that in many ways, including the Presidential Medial of Freedom. She was also a philanthropist with a particular interest in animal welfare.

I don’t know if most of the news reports of Doris Day’s death will adequately express the magnitude of her fame as a singer and movie actress. She was publicly recognized for that in many ways, including the Presidential Medial of Freedom. She was also a philanthropist with a particular interest in animal welfare.

A more jaded generation might dismiss The Thrill of It All for what it was, fluff, but it was designed as nothing more than entertainment, and it has entertained us again and again, and we have already planned to watch it again so that we can renew our appreciation for Doris Day. I know the feeling will quickly be dispelled, but we’ll give in to the fantasy once again and, when the Boyers have resolved their crisis, we’ll actually believe just briefly, that, no matter what we heard on that last newscast, everything will be all right.

“And the $64 question is ….”

May 5, 2019

JAMES HOLZHAUER/ABC photo

I have never watched Jeopardy, and consequently I have no vested interest in how James Holzhauer has run up his record-setting winning streak. I can’t help knowing, however, that there is a kerfuffle over it in which some critics say Holzhauer is ruining the game for others. If I understand the complaint correctly, the issue is that Holzhauer’s success has as much to do with his mastery of the buzzer as it has to do with the breadth of his knowledge. Considering other moral and ethical issues confronting the Republic at the moment, I’m not sure now much urgency to assign to this one.

Dr. JOYCE BROTHERS/Denver Post

The dust-up did remind me, though, of Dr. Joyce Brothers, the psychologist, who was known for the bulk of her career as a television personality and author but who first burst into the public’s consciousness as a contestant on The $64,000 Question. Several of the contestants on that show become instant celebrities. In Joyce Brothers’ case, the immediate interest was in the fact that this young woman was presenting herself as an expert on boxing. I have read that the producers recommended that topic to her, but I don’t know if that is true.

Dr. Brothers decided to seek a spot on the show in 1955 in order to shore up her family’s finances while she was caring for her daughter and her husband, Milton, was in a low-paying medical residency. She had quit teaching positions at Columbia University and Hunter College in order to stay home with her child.

HAL MARCH/Host of “The 64,000 Question”/TV Guide

Whether she or the producers chose the topic, Dr. Brothers was not historically a boxing aficionado. Apparently a person with a strong will and outstanding capacities for concentration and retention, she memorized dozens of reference books on boxing. As a result, she won the top prize. Two years later, she won the top prize on The $64,000 Challenge in which she was pitted against seven experts on the prize ring.

The $64,000 Question was later mired in scandal as it was revealed that some of the contestants had been fed answers in advance, but Dr. Brothers was not implicated in any such scheme. In fact, it has been reported that the producers tried to derail her progress by throwing obscure questions at her, but she answered them correctly.

Whether Dr. Brothers’ approach was any less in the spirit of the show than Holzhauer’s, I’ll leave to minds more acute than my own.

PHIL BAKER

Meanwhile, the name of The $64,000 Question obviously derives from the idiomatic expression “The $64 question,” meaning the most important or perplexing question in a given situation. The idiom itself originated on a radio show of the 1940s, Take It or Leave It, on which the top prize was $64—about $925 today—which a person won by answering “the $64 question.” The big prize was paid in 64 silver dollars.

Time magazine reported at the time as follows:

“Take It or Leave It gives each of five people from the studio audience a chance to answer seven questions correctly (or quit with a cash prize after any number of correct answers less than seven). Seven correct answers in a row nets the maximum $64.”

Members of the studio audience would encourage or heckle the contestants with each decision to take the money and run or move on to the next level.

The host of the show was a comic actor named Phil Baker. Time, reporting in 1944, gave this account of an incident that reflects the character of the show:

“The program pays out about $250 a week, mostly to servicemen on leave and other citizens who can use the money. Men are much more apt to shoot the $64 works than women. Men are also more apt to get Phil Baker in the kind of trouble he encountered recently when a sailor, asked to give the navy definition of ‘noise,’ gave not ‘celery,” which was right, but ‘Boston beans.” Baker gave the sailor $64 and told him to get back to his ship.”

Apparently, the producers of Take It or Leave It didn’t have to worry about ringers.

“Why is your head higher than mine?”

May 2, 2019

RAMA X/Anadolu Agency

I read a long story from Reuters today about Maha Vajiralongkorn Bodindradebayavarangkun—not a household word in the United States but the king in Thailand. He became the monarch in 2016 upon the death of his father, and he is going to be formally crowned on Saturday. He is also, and more conveniently, known as Rama X.

According to Reuters, the king runs a tight ship. He has taken direct control of the family fortune, which is almost too great to be calculated. A career soldier himself, he has the support of the military in his authoritarian posture—usually not a good sign.

Rama X, Reuters reported, has established an enormous volunteer corps in Thailand, more than five million civilians who don uniforms and scurry around cleaning up public places, helping police direct traffic, and generally making themselves useful. They start each project by lining up to salute a portrait of the king.

RAMA IV

Reading about this king called Rama reminded me of a Rama of a different sort who ruled that country when it was known as Siam—Rama IV, also known as Mongkut, who was in power from 1851 to 1868.

The western world, me included, probably would be oblivious to Rama IV if it weren’t for accounts in literature, film, and theater, of the experiences of the English tutor Anna Leonowens. As it is, however, these romanticized versions of the teacher’s interaction with the king have made him a well-known figure.

But the image of Rama IV embedded in western consciousness, notably by Yul Brynner’s portrayals on film and on the stage, only vaguely resembles the real man. It is true that Rama wanted to protect Siam from colonization by a European power and that he wanted to introduce modern ideas to the Siamese people. And it is true that to some extent he achieved these goals, although the reality was not as simple or successful as Oscar Hammerstein would have it.

In keeping with Siamese expectations for young men, Rama became a Buddhist monk when he was twenty years old, and he led a reform movement in monasticism. He studied Latin, English, and astronomy, and he became a close friend of Bishop Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix, the popular and influential apostolic vicar in Bangkok—the envoy of the pope.

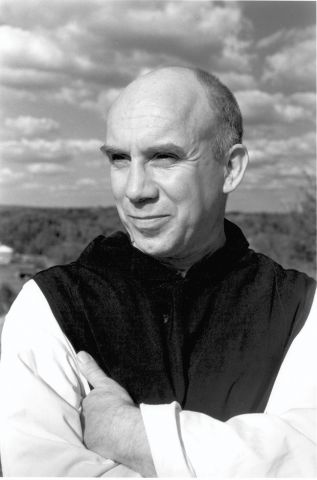

THOMAS MERTON

Rama’s philosophical inquiry attracted the attention of the Trappist monk Thomas Merton—a student of Buddhism—who recorded in his journal the king’s observation that “There is nothing in this world which can be clung to blamelessly, or which a man clinging thereto could be without blame”—an idea that Pope Francis might endorse.

In his effort to establish Siam’s place among the community of nations, King Rama corresponded with world figures including Abraham Lincoln. Although it has often been written that Rama offered to send Lincoln elephants to use against the Confederacy during the Civil War, it appears that the king actually wrote to James Buchanan, Lincoln’s predecessor, offering the animals as beasts of burden. By the time the letter reached the United States, Lincoln was president, and he responded, explaining that the climate might not be suitable for elephants and that Americans were relying on steam engines to do heavy hauling.

POPE PIUS IX

In 1861, Rama wrote an expansive letter to Pope Pius IX, addressing him as the “Holy Father of the Catholic Christian World.” The letter was dictated by the king, taken down in Siamese by a scribe, translated by the king into a rather stilted English, and carried to Rome by Pallegoix. This letter is now in the Vatican Museum.

The king wrote that although Siamese monarchs for centuries had practiced Buddhism, they had also allowed people to practice other faiths unmolested and had welcomed refugees from places such as China and what is now southern Vietnam where Christians in particular were persecuted. Rama mentioned that Pius IX, in a letter hand delivered by Pallegoix, in 1852, had specifically asked that Catholic missionaries and other Christians in Siam be protected.

What is most compelling about this letter is the king’s frequent references to religious tolerance. After all, he wrote, the path to internal happiness and eternal life “is in fact difficult to be exactly known.’’ In this letter, the king asks “the Superagency of the Universe”—in other words, the one God—to confer “temporal and spiritual happiness” and eternal life on the pope. Some commentators have pointed out that the notion of one God is not a part of Buddhist thought, and that the king probably used this expression out of deference to the pope’s beliefs.

Rama’s interaction with the pope and his comments in this letter suggest that he would embrace an idea expressed by Pope Francis in his apostolic letter “Amoris Laetitia”:

“Keep an open mind. Don’t get bogged down in your own limited ideas and opinions, but be prepared to change or expand them. The combination of two different ways of thinking can lead to a synthesis that enriches both. … We need to free ourselves from feeling that we all have to be alike.”

The emperor-to-be and me

April 30, 2019

Crown Prince Akihito tries on a Yankee cap for Casey Stengel and the future Empress Michiko/Associated Press

Considering the amount of time we spent at Yankee Stadium during my youth and adolescence, it was inevitable that we would see some familiar faces. These included Jimmy Powers, John Wayne, Sidney Poitier, and Faye Emerson. We also saw a face that was unfamiliar to us but not to a lot of other people who were in the ballpark that day—Crown Prince Akihito of Japan, who was sitting just to the left of the Yankee dugout with his wife, the former Michiko Shōda.

Crown Prince Akihito throws out the first ball on October 2, 1960. My dad and I are clearly visible in the background./Getty Images

It was October 2, 1960, the last day of that season, and the prince got the proceedings under way by throwing out the first ball. He must have felt right at home; baseball was introduced in Japan in 1872, and it’s still one of the most popular sports for both spectators and participants. Akihito himself played some baseball, although I think he spent more time playing tennis.

Hirihito was still emperor of Japan in 1960, and his oldest son had been invited to the United States by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who once had had a different kind of relationship with the royal family. We were sitting a couple of dozen rows behind Akihito and throughout the game we watched a steady stream of Japanese people slip down to pay their respects to him.

DALE LONG

To these spectators, the news of the day was of secondary importance: The Yankees won their 15th game in a row when Yankee first baseman Dale Long hit a home run in the bottom of the ninth inning, and the Yankees beat the Red Sox, 8-7.

How much Akihito knew about Dale Long I am not aware, but there was a lot worth knowing. Long was in the eighth of his ten major-league seasons when he hit that home run, and the Yankees rewarded him by shipping him to the Washington Senators. He came back to the Yankees for 55 more games in his last two seasons, 1962 and 1963.

JIGGS DONAHUE

In 1956, Long set a major-league record by hitting home runs in eight consecutive games. That record has been matched twice, but never surpassed. In 1959, he tied another record by hitting back-to-back pinch-hit home runs. Although he was a career first baseman, in two games with the Chicago Cubs in 1958, he became the first catcher to throw left-handed since Jiggs Donahue who was a catcher and first baseman for several teams between 1900 and 1909.

I was 18 years old in 1960, and I’m sure I didn’t give much thought to Akihito, who became emperor and now has abdicated in favor of his son, beyond the fact that the folks who were trying to get up close to him kept standing in front of our box and blocking our view.

QUEEN MARGRETHE II

Since then, I have wondered about modern states that still have monarchies. I raised the question once while I was having lunch with a chemist in Denmark. Why does one of the more advanced societies in the world still have a monarch? Apparently no one had asked him that before. He kind of sputtered around for a while until, referring to Margrethe II, he said, “Well, she is Denmark, isn’t she?” And then, since I had got him to thinking about the issue, he said that we Americans only delude ourselves that we don’t have royalty. We simply invest the same respect and adulation in the president and first lady and in other public figures. Fair enough.

Many years ago, I watched a game from the press box at Yankee Stadium, and the reporters were informally playing baseball trivia, trying to stump each other with questions about guys like Jiggs Donahue. There was a man standing behind the press box seats, and he was kibitzing in this contest. At one point, the reporter sitting next to me asked me, “Do you know who this is? It’s Dale Long!” It wasn’t Ted Williams or Stan Musial, but it didn’t matter. It was Dale Long, and he had played major-league baseball—major-league baseball!—something a relative handful of American men could say over the previous century and a half.

Royalty comes in many forms, and Dale Long was more than good enough for me.

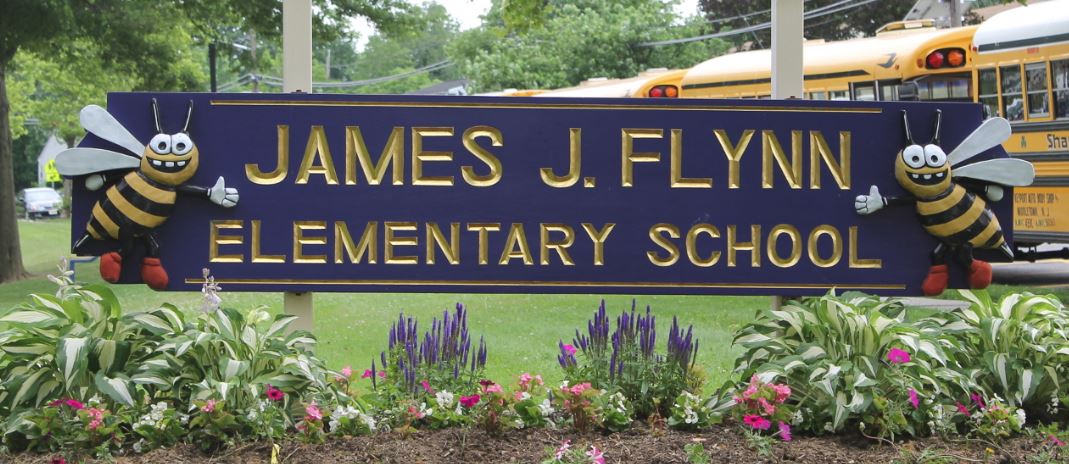

When I was a newspaper reporter, I was assigned to cover the dedication of a school in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, that was named after a former mayor, James J. Flynn Jr. During the ritual, Jay Flynn, as everyone knew him, stood next to me, and at one point he leaned toward me and whispered in his gravelly voice, “They should never name a building after someone who is still alive. It’s too risky.”

When I was a newspaper reporter, I was assigned to cover the dedication of a school in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, that was named after a former mayor, James J. Flynn Jr. During the ritual, Jay Flynn, as everyone knew him, stood next to me, and at one point he leaned toward me and whispered in his gravelly voice, “They should never name a building after someone who is still alive. It’s too risky.”

Jay Flynn never made the Perth Amboy school district regret its decision and, nearly a half century later, the James J. Flynn Elementary School goes on serving the needs of the city’s youngsters. Still, I got his point. Around that same time, the name of a United States senator from New Jersey was removed from a major railroad station, because he had been convicted of accepting bribes and was sentenced to federal prison.

MICHAEL JACKSON visits the Gardner Street Elementary School/elusiveshadow/com

And lo, I now read in the Los Angeles Times that some folks are having second, or third, thoughts about honoring the late entertainer Michael Jackson by naming an auditorium after him in the Gardner Street Elementary School, where he was once a pupil. Jackson visited the school in 1989 to express his gratitude. In 2003, after Jackson was arrested and accused of abusing minors—he was acquitted two years later—his name over the auditorium doors was covered up. But after the singer died at least some of the public and school authorities had another change of heart, and “Michael Jackson Auditorium” was restored. And now, because of the recent documentary Leaving Neverland, which, I understand, renews accusations of abuse of minors, the propriety of honoring Jackson at an elementary school, of all places, has again been called into question.

Of course, the risk attached to heaping praise on someone doesn’t end with the person’s death. I am not equating the two episodes, but this Jackson business comes up in the same week as the absurd decisions by the New York Yankees and Philadelphia Flyers to stop playing Kate Smith’s rendition of “God Bless America” at their games and, in the Flyers’ case, to remove a statue of the singer from outside the team’s arena—all because of two racially troublesome songs that she recorded nearly ninety years ago.

HARMON KILLEBREW/Jim McIsaac/Getty Images

In the midst of all this, word came this month in the Idaho Statesman that, pursuant to a House Resolution passed in December, the post office in the town of Payette (2017 pop. 7,434) has been named after Harmon Killebrew, a native of the place and one of the great baseball sluggers of the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. A 13-time All Star, Killebrew played almost all of his career with the franchise known first as the Washington Senators and then as the Minnesota Twins. While he was playing major league ball, Killebrew joined the Church of Latter Day Saints, the Mormons, and he neither smoked nor drank. He was a gentleman on the field, even to the extreme of complimenting umpires on tough calls.

When Killebrew died in 2011, Twins President David St. Peter recalled Killebrew’s prodigious hitting, his role in establishing the Minnesota baseball franchise, but also the “class, dignity and humility he demonstrated each and every day.” When a writer for Sports Illustrated asked Killebrew if he had a hobby, Killebrew said, “Just washing the dishes, I guess.”

What do you say, Jay? Shall we take a chance?

The Songbird of the South

April 19, 2019

KATE SMITH

Should we chip Abraham Lincoln’s image off of Mount Rushmore, because he said that black and white people could not live together in peace; because he believed the white race was superior; or because his favored disposition of freed slaves was not to establish them as American citizens with full rights but rather to ship them to a colony in Liberia?

Or should we evaluate Abraham Lincoln in the context of his whole life and conclude that, whatever disagreements we may have with him, the country is better off overall because he lived?

And what of Kate Smith, the “songbird of the South”?

In the 1930s, she recorded one song, “That’s Why Darkies Were Born,” that is racially problematic and another, “Pickaninny Heaven,” that is just plain offensive. I say the first song was problematic, because it appears that the lyricist, Lew Brown, intended it as a parody of racist attitudes. That interpretation might be validated by the fact that Paul Robeson also recorded the song. There is no such room for interpretation of “Pickaninny Heaven,” a morbid and condescending lyric that Smith first addressed, on radio, to “a lot a little colored children listening in an orphanage in New York City.” And Smith also was featured in a cartoon advertisement for Calumet Baking Powder that included a stereotypical image of the turbaned black cook and a “mammy doll” supposedly sent to Smith by a fan of Smith’s recipe book.

In the 1930s, she recorded one song, “That’s Why Darkies Were Born,” that is racially problematic and another, “Pickaninny Heaven,” that is just plain offensive. I say the first song was problematic, because it appears that the lyricist, Lew Brown, intended it as a parody of racist attitudes. That interpretation might be validated by the fact that Paul Robeson also recorded the song. There is no such room for interpretation of “Pickaninny Heaven,” a morbid and condescending lyric that Smith first addressed, on radio, to “a lot a little colored children listening in an orphanage in New York City.” And Smith also was featured in a cartoon advertisement for Calumet Baking Powder that included a stereotypical image of the turbaned black cook and a “mammy doll” supposedly sent to Smith by a fan of Smith’s recipe book.

IRVING BERLIN/Masterworks Broadway

Because of those two songs, recorded nearly ninety years ago, the New York Yankees, the team that didn’t integrate until 1955, and the Philadelphia Flyers announced that they would stop playing Smith’s recording of “God Bless America” at their games, and the Flyers said they would cover the statue of Smith outside their arena.

Full disclosure: I have been a fan of Kate Smith the singer since I was a kid listening to her radio show with my mother. But I have also long known that Kate Smith and I would have had serious philosophical differences. Though she had been a favorite of Franklin Roosevelt, she became very conservative and nationalistic, and, I gather, kind of a knee-jerk patriot who was not inclined to question authority. Her recording of “God Bless America,” which Irving Berlin wrote specifically for her, famously inspired Woody Guthrie to write “This Land is Your Land” in response.

JOSEPHINE BAKER

On the other hand, Kate Smith sold $600-million worth of war bonds during World War II, more than any other individual, and the number of her appearances before troops during that war was exceeded only by Bob Hope. And it’s worth mentioning here that in 1951—four years before the Yankees integrated—the highly controversial Josephine Baker, made her first American television appearance on The Kate Smith Evening Hour, a show that was produced by Smith’s manager, Ted Collins. Baker, who had returned to the United States that year after a long absence, had campaigned, during her U.S. tour, against segregation of audiences. After a spat with Walter Winchell in which he suggested that she had Communist leanings, Baker’s work visa was revoked, and she returned to France. Baker, by the way, had once appeared in blackface, a sin for which I believe she has long since been forgiven.

Perhaps it’s because racial bias has persisted for so long in this country that we tend to err on the side of righteousness, but in doing so, we should not lose our sense of balance.