Books:”The Assassin’s Doctor”

March 5, 2016

In the 1936 film Prisoner of Shark Island Samuel Mudd is portrayed (by Warner Baxter) as a well-meaning country doctor who unwittingly abetted the escape of John Wilkes Booth and wound up in a federal prison on an island in the Caribbean. He is pardoned after stemming a yellow fever epidemic that swept the prison.

In the 1936 film Prisoner of Shark Island Samuel Mudd is portrayed (by Warner Baxter) as a well-meaning country doctor who unwittingly abetted the escape of John Wilkes Booth and wound up in a federal prison on an island in the Caribbean. He is pardoned after stemming a yellow fever epidemic that swept the prison.

It’s a good story, but it isn’t entirely true. The truth, some might think, is even more interesting, and it is laid out in detail in The Assassin’s Doctor by Robert K. Summers.

Summers, a great-grandson of Dr. Mudd, has written several books on this and related subjects, but he is not an apologist for his forebear. He seems more interested—particularly in this book—in spreading the record before the reading public.

Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas Islands, where Dr. Mudd was imprisoned for four years.

Booth murdered Abraham Lincoln just as the Civil War was ending, and the reaction of the federal government—particularly of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton—was affected by the intense feelings rippling through the country, feelings that included fear, disillusionment, desperation, and paranoia.

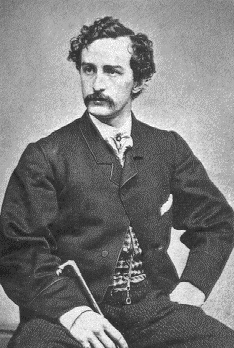

After shooting Lincoln, Booth jumped from the presidential box to the stage of Ford’s Theatre, breaking a leg. He stumbled out of the theater, mounted a waiting horse, and galloped off to Maryland where, in the company of David Herold, one of his co-conspirators, he arrived around 4 in the morning at the home of Dr. Mudd.

Aroused from his sleep, Dr. Mudd took Booth in, put a splint on the broken leg, and provided Booth with a makeshift pair of crutches. Booth remained at Dr. Mudd’s home until the following day, and then left with Herold, heading for Virginia where Herold surrendered and Booth was shot to death by a Union soldier.

Dr. SAMUEL MUDD

Dr. Mudd did not tell anyone about his visitors until several days later, and even then he didn’t do so directly but asked his cousin, Dr. George Mudd, to notify federal authorities in a nearby town. Military personnel visited Samuel Mudd’s home where the Mudds eventually turned over a boot that had been cut from Booth’s leg and that bore the inscription “J. Wilkes.”

Dr. Mudd was arrested, charged with conspiracy, tried by the same military commission that condemned to death three men (including Herold) and one woman (Mary Surratt); Dr. Mudd was sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas islands south of Key West. He was pardoned in 1869 by President Andrew Johnson after working diligently to treat victims of yellow fever at the prison and contracting the disease himself.

There are no serious disagreements about these facts, but there is a lingering discourse about certain aspects of Dr. Mudd’s behavior. The most important question is whether Dr. Mudd recognized Booth when the assassin came calling with his broken leg. Dr. Mudd had met Booth before, when the actor was in the neighborhood ostensibly looking at real estate and seeking to buy a horse. But the doctor and his wife, Sarah, maintained that Booth was wearing false whiskers when he came seeking help with his injury and that Dr. Mudd did not recognize him and had no reason to suspect him. The Mudds’ account was that Booth left their house on Saturday, April 15, while Dr. Mudd was absent, and that Mrs. Mudd noticed the false whiskers at that time. According to this version of events, when Dr. Mudd resolved to notify authorities about these now-suspicious men, Mrs. Mudd prevailed on him to stay at home inasmuch as the men might still be in the area and might pose a danger to the family. So Booth used his cousin as a surrogate messenger.

I think the consensus among historians now is that Dr. Mudd’s acquaintance with Booth was more than the incidental encounter Dr. Mudd described, and that Dr. Mudd participated in conversations with Booth and others concerning Booth’s earlier plan to kidnap Lincoln and take him to Richmond, hoping to enable the Confederate government to negotiate a release of military prisoners. Dr. Mudd was a slave holder and a Southern sympathizer living in a border state, although not an activist against the Union government. It is unlikely, however, that he knew anything about Booth’s decision to murder Lincoln, both because Booth seems to have made that decision only shortly before carrying out the murder and because Dr. Mudd’s character suggests that he would not have agreed to have any part in such a crime. If he did help facilitate Booth’s escape, his primary motive might have been to purge the Mudd household of a murderer.

I think the consensus among historians now is that Dr. Mudd’s acquaintance with Booth was more than the incidental encounter Dr. Mudd described, and that Dr. Mudd participated in conversations with Booth and others concerning Booth’s earlier plan to kidnap Lincoln and take him to Richmond, hoping to enable the Confederate government to negotiate a release of military prisoners. Dr. Mudd was a slave holder and a Southern sympathizer living in a border state, although not an activist against the Union government. It is unlikely, however, that he knew anything about Booth’s decision to murder Lincoln, both because Booth seems to have made that decision only shortly before carrying out the murder and because Dr. Mudd’s character suggests that he would not have agreed to have any part in such a crime. If he did help facilitate Booth’s escape, his primary motive might have been to purge the Mudd household of a murderer.

All the questions about what Dr. Mudd knew and when he knew it are explored in this book. Summers also includes extensive documentation, including many letters that Dr. Mudd wrote to his wife and others while he was a prisoner at Fort Jefferson. These letters include a description of his one attempt to escape from the prison, the harsh conditions under which he and the other prisoners lived, his relationship with other men who were sentenced in connection with the conspiracies against Lincoln, and his heroic part in stemming the yellow-jack epidemic. The average reader might not want to read all of these documents—although a history wonk such as me might devour them—but they do present in a convenient collection an opportunity to hear history unfolding in the voices of those who were taking part in it.

Books: “Worst Seat in the House”

February 13, 2016

Last summer, I wrote a post here about Scott Martelle’s book, “The Madman and the Assassin,” which was a biography of Thomas “Boston” Corbett, the eccentric soldier who shot John Wilkes Booth. What was interesting about that book, besides the fact that Martelle executed it so well, was the fact that in the 150 years that elapsed since Booth died, no one else had written a book-length account of Corbett’s life. Now, hard on Martelle’s heels, comes Caleb Jenner Stephens, with a rare and perhaps unique book-length account of the life of Henry Rathbone, one of only four people present when Booth murdered Abraham Lincoln. Rathbone, an army major at the time, and his fiancé, Clara Harris, joined Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln at Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865 for a performance of the comedy Our American Cousin.

The only reason the couple accompanied the Lincolns that night was that everyone else who had been invited—notably including General Ulysses S. Grant and his wife, Julia—had declined. The advance chatter that the Grants and the Lincolns might attend together just days after Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia had caused some excitement in Washington, but Julia Grant was one of many people in the capital who could not abide Mary Lincoln, so the Grants avoided the appointment by repairing to New Jersey to visit their children. Rathbone, who was sitting in the rear of the presidential box when Booth entered, confronted the assassin after the murder had been committed and sustained a serious knife wound in his left arm.

Despite the injury, he tried unsuccessfully to prevent Booth from leaping from the box to the stage from whence he made his escape. Rathbone, who came from a wealthy Albany family, later married Clara Harris, who was also his stepsister, and the couple had three children, including U.S. Representative Henry Riggs Rathbone of Illinois. Rathbone recovered from the wound to his arm, but his mental health seems to have been permanently impaired by his experience at the theater and especially by the fact that he had been unable to either prevent Lincoln’s death or keep Booth from escaping. It was unreasonable for Rathbone to assume guilt for this, but the event was so sudden and shocking that reason didn’t play a part in his reaction to it. Stephens makes that argument, in some detail, that Rathbone suffered from what is now known as post traumatic stress syndrome. The author also explores an account of the murder—raised in a contemporary publication—which holds that Rathbone saw Booth enter the presidential box before the murder and rose to ask Booth what business he had there, but was brushed aside as Booth approached the president from behind and fired the fatal shot.

I am not aware that this version appears in any public record. Stephens attributes it to The Public Ledger, a daily newspaper then being published in Philadelphia. According to The Public Ledger, Clara Harris gave this alternative version during an interview with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Stephens gives weight to this account and repeatedly—and, I think, unfairly—refers to Rathbone’s “failure to protect the president.” In one instance, in fact—in a stunning exercise of hyperbole—the author accuses Rathbone of “failing the whole world.”

Rathbone remained in the army until 1879 and retired with the rank of brevet colonel. He and his family were living in Germany on December 23, 1883, when, after many years of psychic and emotional instability, he murdered Clara and tried to commit suicide. He was consigned to a reasonably comfortable asylum in Germany for the remaining twenty-seven years of his life. This book suffers from bad grammar and syntax to a degree that is very distracting. However, Stephens has made a contribution to the literature surrounding the murder of Abraham Lincoln by compiling a chronicle that has been neglected.

Books: “The Madman and the Assassin”

June 4, 2015

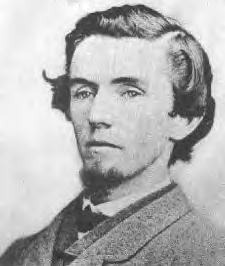

I don’t know how John Wilkes Booth thought his journey was going to end, but I’m sure Boston Corbett didn’t figure in his plans.

Booth made a sincere effort to get away with murdering Abraham Lincoln. With one of his accomplices, David Herold, he was heading south, hoping to get deep into the former Confederacy where folks might see what he did–sneaking up on a man and shooting him in the back of the head–as something more than an act of cowardice. Like many criminals, however, Booth left a trail, and federal detectives and troops tracked him down to a Virginia farm, cornered him and Herold in a barn, and set fire to the structure. Herold gave up and eventually hanged, but Booth, who was armed, stayed in the burning building. Corbett, an army sergeant, watched the assassin through an opening in the wall of the barn and–as he later said–thinking that Booth was about to fire on the soldiers outside, shot him in almost the same place that Booth’s bullet had struck Lincoln. Booth fell, paralyzed, and died after being removed to the farmhouse porch.

Thomas “Boston” Corbett, the man who killed Booth, is the subject of this engrossing book by Scott Martelle. It’s an important contribution to the history of the epoch surrounding the end of the Civil War and the murder of Lincoln; relatively little has been written about Corbett and some of what has been written has been incorrect. By Martelle’s account, Corbett was a complicated and eccentric character. He frequently worked as a hatter — specifically as a finisher — and that meant that he was exposed to a great deal of mercury. That has led to speculation that mercury poisoning led to Corbett’s peculiarities as it led to the odd behavior of many others. His lifelong vocation, however, was not as a hatter but as a Christian preacher. He was deeply religious in his own way, so much so that Martelle reports that Corbett castrated himself while still a young man in order to spare himself the inclination to sexual sin. His overriding goal was to live as a Christian — as he understood that term — every hour of every day. Whatever his foibles, he performed many acts of kindness in his pursuit of that ideal.

He served four separate hitches in the Union Army during the Civil War, and a colleague later wrote of him, “He was a very religious man, faithful at his post of duty, a good speaker, and a skillful and helpful nurse to those who were ill or in distress, and [he] knew no fear.” Still, he was once court-martialed for walking off his post, and he threatened to kill a fellow soldier in order to dissuade him from picking blackberries on the Sabbath. Corbett thought the war was justified and reportedly had no qualms about killing enemy soldiers, although he prayed for them before pulling the trigger.

At one point, Corbett was an inmate at the notorious prison camp in Andersonville, Georgia. The conditions there were so heinous that they permanently damaged Corbett’s health. He did survive, however, and returned to service, and so was available when a cavalry detachment was sent to hunt down Booth and Herold.

In the wake of Booth’s death, some people regarded Corbett as a hero, and some condemned him. Although there were claims to that effect at the time, Martelle determined that there was no order to take Booth alive. Corbett was in demand as a speaker and, one imagines, as a curiosity, but in the long run he had a difficult time sustaining himself. In desperation, he moved to Kansas and tried his hand at raising livestock and selling the wool from his sheep.

Eventually, he became unglued, was confined to a asylum, escaped, and vanished from history.

If Corbett hadn’t shot Booth, Booth would have hanged anyway. Whether he would have revealed anything to assuage the doubts, which still linger, about the culpability of Mary Surratt and Dr. Samuel Mudd, we can only conjecture. As it is, Mrs. Surratt hanged and Dr. Mudd was sent to the federal prison in the Dry Tortugas Islands off Key West but pardoned after he helped stem a yellow-fever epidemic among the inmates.

But Corbett did shoot Booth, and, like Jack Ruby after him, became a key if shadowy player in a great drama. Martelle, a diligent reporter and a skillful writer, has done us a service by recreating the life of this strange man.

Books: “Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man”

December 18, 2012

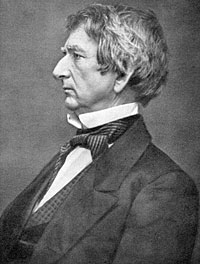

If the Chicago Tribune had it right, William H. Seward was the prince of darkness.

In 1862, when Seward was Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state and the Civil War seemed as likely as not to permanently destroy the federal union, the “world’s greatest newspaper” knew whom to blame. Seward, the Tribune said, was “Lincoln’s evil genius. He has been president de facto, and has kept a sponge saturated with chloroform to Uncle Abe’s nose all the while, except one or two brief spells.” The Boston Commonwealth was about as delicate in its assessment of Seward: “he has a right to be idiotic, undoubtedly, but he has no right to carry his idiocy into the conduct of affairs, and mislead men and nations about ‘ending the war in sixty days.’ ”

This demonic imbecile, as some editors would have it, is the subject of Walter Stahr’s comprehensive and engaging biography, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man. Stahr has a somewhat different take than the Tribune’s Joseph Medill. While Stahr acknowledges that Seward was overly optimistic about prospects for the federal government to prevail over the seceding states, and while he acknowledges that Seward sometimes turned to political chicanery and downright dishonesty, he also regards Seward as second in importance during the Civil War era only to Lincoln himself.

Seward, a former governor of New York and United States Senator, was by Stahr’s account, very close to Lincoln personally, which probably contributed to the rancor directed at Seward from others in the government who wanted the president’s attention. Their relationship was interesting in a way that is analogous to the relationship between Barak Obama and Hillary Clinton in the sense that Seward was Lincoln’s chief rival for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. Seward’s presidential ambitions, which were advanced by fits and starts by the political instigator Thurlow Weed of New York, are well documented in this book. But, as Stahr makes clear, Seward’s disappointment at losing the nomination to Lincoln did not prevent him from agreeing to serve with Lincoln at one of the most difficult periods in the nation’s history nor from serving him loyally.

As important an office as secretary of state is now, it was even more so in the 19th century, because its reach wasn’t confined to foreign affairs. It wasn’t uncommon for the secretary of state to be referred to as “the premier.” At first, Seward’s view of the office might have exceeded even the reality; he seems to have thought at first that he would make and execute policy and Lincoln provide the face of the administration. Lincoln soon made it clear who was in charge, and he and Seward worked well together from then on.

Seward’s service in Lincoln’s administration nearly cost him his life on the night that Lincoln himself was murdered by John Wilkes Booth. One of Booth’s accomplices, Lewis Payne, forced his way into the house where Seward was lying in bed, recovering from injuries he had sustained in a serious carriage accident. Payne, who was a wild man, tore through the place, cutting anyone who tried to stop him, and he attacked Seward, slashing his face. Payne fled the house — he eventually hanged for his crime — and Seward survived.

After the double trauma of Lincoln’s death and Seward’s own ordeal, it would have been understandable if Seward had withdrawn from public life. Seward wasn’t cut of ordinary cloth, however, and he agreed to remain at his post in the administration of Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson. Johnson was an outstanding American in many respects—he was the only southern member to remain in his U.S. Senate seat after secession, and he gave up the relative safety of the capital and took his life in his hands when Lincoln asked him to serve as military governor of Tennessee — but he was not suited for the role that was thrust on him by Booth.

Stahr explores the question of why Seward stayed on during the troubled years of Johnson’s tenure. He infers, for one thing, that Seward agreed with Johnson’s idea that the southern states should be quickly restored to their place in the Union without the tests that the Republican majority in Congress, and especially the “radical” wing of the party, wanted to impose. Stahr also writes that Seward believed that if Congress succeeded in removing Johnson on impeachment charges that were politically motivated it would upset the balance of power in the federal government for decades to come.

I mentioned Seward to a co-worker today, and she said, “of the folly?” She was referring to the purchase of Alaska, which Seward completed during Johnson’s administration. Stahr writes that much of the press supported the purchase of “Russian American” at first, and although the term “folly” was tossed about later, prompted in part by Seward’s further ambitions for expansion, the epithet was never widely used.

Alaska was only one of Seward’s achievements. He was a skillful diplomat who was equipped to play the dangerous game that kept Britain and France from recognizing the Confederate States of America. Although he may have underestimated the threat of secession and the prospects for a protracted war, he was at Lincoln’s side every step of the way—playing a direct role, for instance, in the suspension of habeas corpus and the incarceration of suspected spies without trial. He was not an abolitionist—and in that respect he disagreed with his outspoken wife, Frances— but Seward was passionate about preventing the spread of slavery into the western territories. He believed that black Americans should be educated. He did not support fugitive slave laws and even illegally sheltered runaway slaves in his home in Auburn, N.Y.

Seward was a complicated character who stuck to high moral and ethical standards much of the time, but was capable of chicanery, deceit, and maybe even bribery if it would advance what he thought was a worthy purpose.

A world traveler, he was one of Washington’s leading hosts, known for his engaging manner, and yet with his omnipresent cigar and well-worn clothes he appeared to all the world as something akin to an unmade bed. Henry Adams, who admired Seward, described him as “the old fellow with his big nose and his wire hair and grizzled eyebrows and miserable dress” who nevertheless was “rolling out his grand, broad ideas that would inspire a cow with statesmanship if she understood our language.”

John Surratt: On the lam in Rome and Alexandria

April 16, 2011

Maybe I’ve read too much about the plot against Abraham Lincoln; that may be why I can’t get up any enthusiasm about Robert Redford’s film “The Conspirator.” For more than 50 years, I’ve been wading through so many accounts either exonerating or condemning Mary Surratt for complicity in the crime, that I’m practically schizophrenic on the subject. I first took interest in the assassination when my dad subscribed to the Reader’s Digest condensed book series. The first book we got included a truncated version of Jim Bishop’s 1955 history The Day Lincoln Was Shot. Being a sucker for a sob story, my first inclination was to sympathize with Mrs. Surratt as an innocent victim of Edwin Stanton’s over-the-top response to the death of the president — which occurred, incidentally, 146 years ago this very day. I was about 14 when I read that book, and I think the idea of a woman being hanged superseded any calm analysis of the evidence.

Maybe I’ve read too much about the plot against Abraham Lincoln; that may be why I can’t get up any enthusiasm about Robert Redford’s film “The Conspirator.” For more than 50 years, I’ve been wading through so many accounts either exonerating or condemning Mary Surratt for complicity in the crime, that I’m practically schizophrenic on the subject. I first took interest in the assassination when my dad subscribed to the Reader’s Digest condensed book series. The first book we got included a truncated version of Jim Bishop’s 1955 history The Day Lincoln Was Shot. Being a sucker for a sob story, my first inclination was to sympathize with Mrs. Surratt as an innocent victim of Edwin Stanton’s over-the-top response to the death of the president — which occurred, incidentally, 146 years ago this very day. I was about 14 when I read that book, and I think the idea of a woman being hanged superseded any calm analysis of the evidence.

I’m probably more suspicious of Mary Surratt now than I was then, although I think the way the defendants were tried in that case was outrageous. Meanwhile, the most interesting figure in that case — well, the most entertaining, anyway — was Mary Surratt’s son John, whose story — as far as I know — has yet to be put on film. John Surratt was 20 years old at the time of the murder, and he had been active as a messenger and a spy for the Confederacy.

Surratt was involved with John Wilkes Booth in a conspiracy to kidnap Lincoln, take him to the Confederate capital in Richmond, and try to exchange him for southern war prisoners. That plot was unwittingly derailed by Lincoln, who changed the travel plans that the conspirators were relying on. It’s well established that Surratt wasn’t among the little circle of characters Booth enlisted after ramping his plan up to murder. But Surratt beat it out of the country as soon as the foul deed was done, leaving his mother behind to face the wrath of a seething Union. He may have been in upstate New York on a spying mission when Lincoln was killed. At any rate, he turned up in Canada and, after his mother had been hanged, he went to England, then to Paris, then to Rome. The unification of Italy hadn’t been completed yet, and John Surratt was able to enlist in the papal army and engage in combat with the forces of Giuseppe Garibaldi. According to Surratt, he wrote to an influential person in the United States to ask if it would be safe for him to return — by which he meant, would he be tried in a civil court or by an illegal court-martial like the one that had convicted his mother.

Surratt was involved with John Wilkes Booth in a conspiracy to kidnap Lincoln, take him to the Confederate capital in Richmond, and try to exchange him for southern war prisoners. That plot was unwittingly derailed by Lincoln, who changed the travel plans that the conspirators were relying on. It’s well established that Surratt wasn’t among the little circle of characters Booth enlisted after ramping his plan up to murder. But Surratt beat it out of the country as soon as the foul deed was done, leaving his mother behind to face the wrath of a seething Union. He may have been in upstate New York on a spying mission when Lincoln was killed. At any rate, he turned up in Canada and, after his mother had been hanged, he went to England, then to Paris, then to Rome. The unification of Italy hadn’t been completed yet, and John Surratt was able to enlist in the papal army and engage in combat with the forces of Giuseppe Garibaldi. According to Surratt, he wrote to an influential person in the United States to ask if it would be safe for him to return — by which he meant, would he be tried in a civil court or by an illegal court-martial like the one that had convicted his mother.

Although his correspondent advised him to stay away for three more years, Surratt decided to take his chances and go home. Before he could do so, however, someone in the Vatican recognized him, and Pope Pius IX ordered him arrested. Surratt was confined to a monastery on a mountain somewhere between Rome and Naples. Meanwhile the Vatican secretary of state informed the United States Secretary of State William Seward, and a man-of-war was dispatched from the Indian Ocean to fetch Surratt. When he was removed from his cell to be transferred to Rome, he broke away from his captors and dove over a wall onto a rock ledge about thirty five feet below. He was momentarily unconscious, but came to himself and scrambled down the mountainside to the village below. As he continued his flight, he fell in with a company of Garibaldi’s troops and told them he was an American deserter from the pope’s forces. They protected him until he departed for Alexandria, Egypt. There, he decided again that he should return to the United States, and he stopped disguising his identity. He was tracked down and arrested and sent home via Marseilles on the U.S. Navy sloop Swatara.

Although his correspondent advised him to stay away for three more years, Surratt decided to take his chances and go home. Before he could do so, however, someone in the Vatican recognized him, and Pope Pius IX ordered him arrested. Surratt was confined to a monastery on a mountain somewhere between Rome and Naples. Meanwhile the Vatican secretary of state informed the United States Secretary of State William Seward, and a man-of-war was dispatched from the Indian Ocean to fetch Surratt. When he was removed from his cell to be transferred to Rome, he broke away from his captors and dove over a wall onto a rock ledge about thirty five feet below. He was momentarily unconscious, but came to himself and scrambled down the mountainside to the village below. As he continued his flight, he fell in with a company of Garibaldi’s troops and told them he was an American deserter from the pope’s forces. They protected him until he departed for Alexandria, Egypt. There, he decided again that he should return to the United States, and he stopped disguising his identity. He was tracked down and arrested and sent home via Marseilles on the U.S. Navy sloop Swatara.

At home, Surratt got his wish, as it were, when he was tried for murder by a civil court in a proceeding that lasted from June 10 to August 10, 1867. The jury was divided — eight voting to acquit and four to convict — and Surratt was a free man. He lectured on his involvement in the Lincoln case without much success. He later became a teacher and eventually worked in the offices of a steamship company. He married, and he and his wife had seven children. He died in 1916.

At home, Surratt got his wish, as it were, when he was tried for murder by a civil court in a proceeding that lasted from June 10 to August 10, 1867. The jury was divided — eight voting to acquit and four to convict — and Surratt was a free man. He lectured on his involvement in the Lincoln case without much success. He later became a teacher and eventually worked in the offices of a steamship company. He married, and he and his wife had seven children. He died in 1916.

John Surratt is one of those captivating figures who flit around the outskirts of historical events which we sometimes think about only in terms of the major players. Judging by his previous relationship with Booth, this story probably would have been very different if Surratt hadn’t been out of town on April 14, 1865. As it is, he comes across as a scamp who makes good copy and probably would make an even better movie.

The text of one of Surratt’s lectures is at THIS LINK.

Hear the voice of Edwin Booth. No, really.

April 12, 2010

I had an opportunity this week to talk to William Henline, a young playwright who is about to introduce a drama about Edwin Booth, the most prominent American actor of the mid and late 19th century and the brother of John Wilkes Booth. The focal point of the play is Edwin Booth’s effort to come to terms with what his brother had done. The dynamics are not the obvious. Edwin and Wilkes Booth lived at politically opposite poles. Wilkes was a Confederate sympathizer and operative who despised Abraham Lincoln, as many people did at the time. Edwin supported the Union, and Henline’s research shows that the only two times Edwin Booth is known to have voted, he voted for Lincoln. The brothers’ political differences ran so deep that they were incapable of discussing the subject.

Still, Henline discerns that there was a fraternal love that underlay this fissure between the brothers and that survived even Edwin’s revulsion and humiliation over the murder of Lincoln. Edwin, it seems, was constitutionally incapable of rationalizing or excusing Wilkes Booth’s crime, but was equally incapable of casting off his sibling — even if he did once say that he didn’t want Wilkes Booth’s name mentioned in his presence.

Edwin Booth’s rooms at the Players Club in New York have been preserved as they were on the day he died in 1893. Near his bed is a portrait of John Wilkes Booth.

Henline also called my attention to the fact that there is a recording available of Edwin Booth reciting part of a speech from William Shakespeare’s “Othello.” The quality is as poor as one might expect from such an early recording, but if you listen to it at THIS LINK, you can follow the text on the screen and understand most of the speech. Considering who Edwin Booth was and when he spoke these words, it’s a stirring experience to sit at a laptop in 2010 and hear his voice.