Books: “The Presidents’ War”

August 5, 2014

When President Martin Van Buren died, 19 of his successors had already been born. At the onset of the Civil War, four of them — John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan — joined Van Buren in that exclusive category, former presidents. That was the only time five former presidents were living at one time until 1993 when Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush were still kicking around. It happened again in 2001 with Carter, Ford, Reagan, Bush, and Bill Clinton. The quintet that formed a sort of elite gallery watching the Union unravel are usually ranked in the bottom dozen or so when retrospective experts, who never faced such decisions, cast their ballots. But none of the former presidents saw themselves that way and, in that rough-and-tumble time, they didn’t pose as aloof elder statesmen while Abraham Lincoln dealt with the crisis of secession. What they did do is the subject of The Presidents’ War by Chris DeRose.

This is an unusual and possibly unique approach to the history of the three decades leading up to the war and the prosecution of the war itself. The Civil War is sometimes remembered simplistically as a war over slavery — either over whether slavery should be permitted in new states as the nation expanded westward or whether it should be abolished altogether. Both of these questions were at issue, but the controversy was more complicated than that because it was intertwined with the evolving understanding of the relationship between the states and what was then often referred to as the “general government” — the federal government. The rights of individual states vis-a-vis the federal government are still the subject of often contentious discourse, but the question was far less settled in the decades before and immediately after the Civil War than it is now.

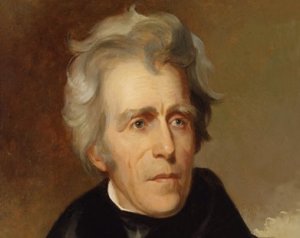

Differing views over that question led to a crisis in 1832 when South Carolina declared that tariffs imposed by the federal government that year and in 1828 were null and void. Andrew Jackson, a tough customer, was president at the time, and he ordered that the duties be collected by whatever means were necessary and he formally declared that states did not have the power to nullify federal regulations or leave the federal union. The crisis was put off, in a sense, by a political compromise; it was put off, but not settled, and it would simmer and occasionally come to a boil until it exploded in secession and war. After Jackson, eight men, beginning with Van Buren, would exercise the executive authority while these fundamental questions remained unresolved and repeatedly threatened to rupture the union. Two of them — William Henry Harrison, the ninth president, and Zachary Taylor, the twelfth president, would die in office and would not play a significant role in government, and one of them, James Knox Polk, the 11th president, would die shortly after leaving office in 1849. Those five who would live to see the nation descend into the bloodiest war in its history had differing points of view on the seminal questions of the time. Although they are usually overlooked or derided in accounts of this period, DeRose explains in detail how they all were engaged in promoting their positions and often were active participants in the political dynamics of the time.

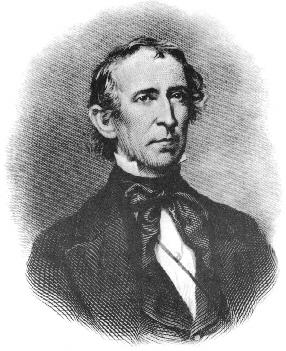

Perhaps the most interesting character DeRose brings back into the light is John Tyler of Virginia, the first man to serve as president without being elected to the office (succeeding Harrison, who died after a month in the White House) and the only former president to become a sworn enemy of the United States. During the administration of James Buchanan, Tyler acted as a go-between seeking an accommodation between the United States and the newly formed Confederacy. Tyler promoted and chaired a ill-fated peace convention in 1861 and then participated in the convention in which Virginia voted to secede from the Union. Tyler was eventually elected to the Confederate Congress, although he died before he took his seat. Although the circumstances were dubious, this last achievement made him one of only four former presidents to serve in public office, the others being John Quincy Adams, Andrew Johnson, and William Howard Taft.

Martin Van Buren of New York, who served one term as president, had ambitions to return to the White House, but they were ultimately frustrated. He was one of many Americans who held that slavery was morally wrong but that it was protected by the Constitution. Although he was initially opposed to the election of Abraham Lincoln, Van Buren ultimately supported him and the war effort. Millard Fillmore, also of New York, was the last Whig president and, therefore, the last president who was not associated with either the Democratic or Republican parties. When the crisis had reached the point of no return and Lincoln called on the northern states to raise troops, Van Buren supported him, as did Fillmore. Van Buren argued that “the attack upon our flag and the capture of Fort Sumter by the secessionists could be regarded in no other light than as the commencement of a treasonable attempt to overthrow the Federal Government by military force. ….”

Fillmore was elected vice president on the ticket with Zachary Taylor and was vaulted into the presidency by Taylor’s death. He, too, skated on the thin ice between his own professed abhorrence of slavery and both the fact that it was protected by the Constitution and his desire to avoid antagonizing the southern states. He was sufficiently repulsed by slavery, in fact, that he raised money and contributed some of his own to enable his coachman to buy his own freedom and that of his family, but Fillmore supported enforcement of the fugitive slave law because it was the law of the land and because, like his four contemporaries, he did not want to provoke the South into Civil War. Three years after he left office, he unsuccessfully ran for president on the ticket of the anti-Catholic American Party, although he himself was not anti-Catholic. Although he was opposed to secession, he did not support Lincoln’s decision to emancipate slaves as a means of expediting an end to the war.

Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire, who was a brigadier general during the war with Mexico, was a Democrat who was opposed to secession but openly supported the institution of slavery in the South. He was a close associate of Jefferson Davis, who became president of the Confederacy, and antagonistic toward Lincoln. Pierce, who was beset by personal tragedy and drinking problems, attempted to undermine Lincoln’s policies by organizing an unprecedented “commission” of the living former presidents to mediate the differences between North and South. The commission, which would have been heavily weighted against Lincoln’s positions, never materialized.

James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, Lincoln’s immediate predecessor, had adopted the problematic view that states did not have a right to secede from the union and that the federal government did not have the power to stop them by force.

Buchanan, who had had a distinguished career, particularly as a diplomat, failed to preserve the peace between North and South and left office stinging with the idea that he would be regarded as a failure as president. It wasn’t known at the time, but he had exerted pressure on the Supreme Court to broaden its pending ruling in the Dredd Scott case to not only determine Scott’s status but to state that Congress did not have the power to prohibit slavery in the western territories. He spent his retirement years at his home in Wheatland, but he persistently trumpeted the idea that his policies were precursors to Lincoln’s. Buchanan busied himself during that time writing a memoir in hopes of vindicating himself, but he is generally regarded as having been hopelessly inept, at least with regard to secession.

DeRose covers a lot of ground in this book, but by telling the story in terms of the presidents who tried to cope with nagging and explosive issues, he brings as clarity to the subject that is not always present in accounts of that complex period. And besides writing a history of the run-up to the war, he provides a chronicle of the evolution of a public office — the presidency — noting that the five former presidents who lived to see secession and war had “feared that he would break the customs of the office that they had established and carefully cultivated. Their concerns were well founded. The American presidency is now a dynamic institution and powerful force for principle in the hands of the proper occupant…. Often American has been bereft of the leadership it wanted. But … in hours of great crisis for the Republic, America has never failed to find the reader to match the moment.”

Books: “The Slaves’ Gamble”

May 9, 2013

Perhaps I just wasn’t paying attention, but my impression is that the War of 1812 didn’t get much air time when I was in elementary and high school. Where American history was concerned, as I recall, it was all about the Revolution and the Civil War. It took me a while to catch up; it was relatively recently that I caught on that the War of 1812 was, in effect, a continuation of the Revolution.

Among the things I didn’t know about the war was that black men, free and slave, fought on both the American and British sides and also on behalf of the Spanish authorities who were futilely trying to hang onto the Florida territories. Gene Allen Smith, a history professor at Texas Christian University, covers that in detail in his book The Slaves’ Gamble: Choosing Sides in the War of 1812.

An important aspect of this story is that the British, strapped for resources because their government was fighting what turned out to be the decisive war with Napoleon Bonaparte in Europe, encouraged American slaves to bolt from their masters and either emigrate to a British possession — notably Nova Scotia — or enlist in military service. Either way, the British promised the slaves their freedom.

Besides filling their ranks, the British saw this strategy as a means of undermining the Southern economy. The number of slaves who took advantage of the opportunity was slight compared to the million-plus who were in bondage at that time, but the fact that the British were welcoming slaves sent shock waves through the South, where white people always feared a slave rebellion.

Although this is a story about a war fought on many fronts over three years, Smith puts a human face on it by providing anecotes about particular black men who played a part in the epoch.

One example was George Roberts, a free Marylander who served during the war on numerous American privateers — private vessels that harassed and even seized British shipping on the U.S. government’s behalf. Another was Jordan B. Noble, who was born a mixed-race slave in 1800 and joined the 7th U.S. Regiment as a drummer in 1813. He served in the Battle of New Orleans and later took part in the Mexican, Seminole, and Civil wars.

A sad if not surprising episode in this history concerned Andrew Jackson, who recruited slaves to help in protecting New Orleans from a British attack. Jackson promised to free the slaves in return for their service, but, Smith writes, never intended to do so. Jackson, according to the author, “committed them to his cause rather than permitting them to assist the British, and this tied them to the United States.”

Allen explains that, once the war was over, the impact of the British strategy had the unintended effect of strengthening the plantation system in the South and opening new territory — namely, what had been the Spanish Floridas—to slavery. In general, the competence and bravery black soldiers and sailors contributed to the American cause during the War of 1812 was not adequately rewarded. On the contrary, some of the worst experiences for black people in the United States were yet to come.

Books: “Emancipation Proclamation”

March 12, 2013

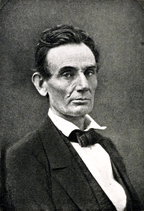

The recent movie Lincoln is serving an important function if it adds some balance to the public perception of the 16th president. No film that I have seen has presented Abraham Lincoln in such realistic terms, and the decision to focus on his campaign to get the 13th Amendment enacted was inspired, because that aspect of Lincoln’s presidency is not well known.

The recent movie Lincoln is serving an important function if it adds some balance to the public perception of the 16th president. No film that I have seen has presented Abraham Lincoln in such realistic terms, and the decision to focus on his campaign to get the 13th Amendment enacted was inspired, because that aspect of Lincoln’s presidency is not well known.

In a way, Lincoln is a victim of his own success. Under his watch, the Union was preserved and human slavery was outlawed in the United States. As a result, Lincoln is enshrined in the national memory as a miracle worker, a savior, almost super human. The apotheosis began almost the moment the public learned of his death.

Among the titles applied to Lincoln is “great emancipator,” but the sobriquet doesn’t reflect Lincoln’s internal struggle and his political struggle over the notion that the federal government should free the millions of people who were being held in bondage in the South when the Civil War erupted.

In Emancipation Proclamation: Lincoln and the Dawn of Liberty, Tonya Bolden spells out the hazardous route Lincoln traveled to his decision to issue the document that fixed his image in history.

In Emancipation Proclamation: Lincoln and the Dawn of Liberty, Tonya Bolden spells out the hazardous route Lincoln traveled to his decision to issue the document that fixed his image in history.

The book is marketed by the publisher, Abrams, as being for young readers but the clear and concise treatment would be serviceable for any adult who wants to catch up on this topic.

Lincoln was progressive for his time. He hated human slavery and would have abolished it if he thought he could. But the relationship between the states and the federal government was still evolving in the mid 19th century, and Lincoln didn’t think Constitution gave the federal government the power to interfere with slavery where it already existed.

Inasmuch as the Civil War erupted shortly after and largely because of Lincoln’s first inauguration,he was preoccupied with one thing, and that was saving the Union. He said in so many words that whatever he did about slavery — abolish it, modify it, leave it alone — he would do only because it would save the Union. In the end, he was true to his word, because the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared free only those people who were being held as slaves in states or parts of states in rebellion against the federal government, was a war measure. Lincoln reasoned that he could take that action as commander in chief even if he couldn’t have taken it as a peacetime president. Even then, he hesitated.

Inasmuch as the Civil War erupted shortly after and largely because of Lincoln’s first inauguration,he was preoccupied with one thing, and that was saving the Union. He said in so many words that whatever he did about slavery — abolish it, modify it, leave it alone — he would do only because it would save the Union. In the end, he was true to his word, because the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared free only those people who were being held as slaves in states or parts of states in rebellion against the federal government, was a war measure. Lincoln reasoned that he could take that action as commander in chief even if he couldn’t have taken it as a peacetime president. Even then, he hesitated.

While Lincoln was considering the advisability of freeing slaves as a way of weakening the southern economy, he had to take into account the potential reaction of the border states — slave states that hadn’t left the Union — as well as the reactions of white Union soldiers who were willing to fight to save the Union but not to free black slaves. Meanwhile, he was under pressure from the swelling abolitionist movement to simply put an end to slavery in one sweeping gesture.

Lincoln also gave a lot of thought to what would become of the slaves once they were emancipated, and his thoughts were shaped by the fact that he didn’t believe in the equality of the black and white races and didn’t think black and white people could live together in peace. Accordingly, his solution was to colonize the freed slaves, preferably in South America or West Africa, even though most slaves at that time had been born in the United States. But by February 1865, Lincoln was publicly endorsing voting rights for at last some educated black men.

This is an attractive book — an art book, really — richly illustrated with images from the period and embellished with break-out quotes from prominent men and women with an interest in the subject of emancipation.

Books: “Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man”

December 18, 2012

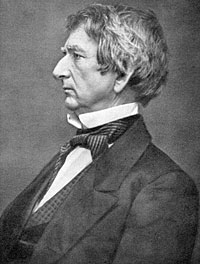

If the Chicago Tribune had it right, William H. Seward was the prince of darkness.

In 1862, when Seward was Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state and the Civil War seemed as likely as not to permanently destroy the federal union, the “world’s greatest newspaper” knew whom to blame. Seward, the Tribune said, was “Lincoln’s evil genius. He has been president de facto, and has kept a sponge saturated with chloroform to Uncle Abe’s nose all the while, except one or two brief spells.” The Boston Commonwealth was about as delicate in its assessment of Seward: “he has a right to be idiotic, undoubtedly, but he has no right to carry his idiocy into the conduct of affairs, and mislead men and nations about ‘ending the war in sixty days.’ ”

This demonic imbecile, as some editors would have it, is the subject of Walter Stahr’s comprehensive and engaging biography, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man. Stahr has a somewhat different take than the Tribune’s Joseph Medill. While Stahr acknowledges that Seward was overly optimistic about prospects for the federal government to prevail over the seceding states, and while he acknowledges that Seward sometimes turned to political chicanery and downright dishonesty, he also regards Seward as second in importance during the Civil War era only to Lincoln himself.

Seward, a former governor of New York and United States Senator, was by Stahr’s account, very close to Lincoln personally, which probably contributed to the rancor directed at Seward from others in the government who wanted the president’s attention. Their relationship was interesting in a way that is analogous to the relationship between Barak Obama and Hillary Clinton in the sense that Seward was Lincoln’s chief rival for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. Seward’s presidential ambitions, which were advanced by fits and starts by the political instigator Thurlow Weed of New York, are well documented in this book. But, as Stahr makes clear, Seward’s disappointment at losing the nomination to Lincoln did not prevent him from agreeing to serve with Lincoln at one of the most difficult periods in the nation’s history nor from serving him loyally.

As important an office as secretary of state is now, it was even more so in the 19th century, because its reach wasn’t confined to foreign affairs. It wasn’t uncommon for the secretary of state to be referred to as “the premier.” At first, Seward’s view of the office might have exceeded even the reality; he seems to have thought at first that he would make and execute policy and Lincoln provide the face of the administration. Lincoln soon made it clear who was in charge, and he and Seward worked well together from then on.

Seward’s service in Lincoln’s administration nearly cost him his life on the night that Lincoln himself was murdered by John Wilkes Booth. One of Booth’s accomplices, Lewis Payne, forced his way into the house where Seward was lying in bed, recovering from injuries he had sustained in a serious carriage accident. Payne, who was a wild man, tore through the place, cutting anyone who tried to stop him, and he attacked Seward, slashing his face. Payne fled the house — he eventually hanged for his crime — and Seward survived.

After the double trauma of Lincoln’s death and Seward’s own ordeal, it would have been understandable if Seward had withdrawn from public life. Seward wasn’t cut of ordinary cloth, however, and he agreed to remain at his post in the administration of Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson. Johnson was an outstanding American in many respects—he was the only southern member to remain in his U.S. Senate seat after secession, and he gave up the relative safety of the capital and took his life in his hands when Lincoln asked him to serve as military governor of Tennessee — but he was not suited for the role that was thrust on him by Booth.

Stahr explores the question of why Seward stayed on during the troubled years of Johnson’s tenure. He infers, for one thing, that Seward agreed with Johnson’s idea that the southern states should be quickly restored to their place in the Union without the tests that the Republican majority in Congress, and especially the “radical” wing of the party, wanted to impose. Stahr also writes that Seward believed that if Congress succeeded in removing Johnson on impeachment charges that were politically motivated it would upset the balance of power in the federal government for decades to come.

I mentioned Seward to a co-worker today, and she said, “of the folly?” She was referring to the purchase of Alaska, which Seward completed during Johnson’s administration. Stahr writes that much of the press supported the purchase of “Russian American” at first, and although the term “folly” was tossed about later, prompted in part by Seward’s further ambitions for expansion, the epithet was never widely used.

Alaska was only one of Seward’s achievements. He was a skillful diplomat who was equipped to play the dangerous game that kept Britain and France from recognizing the Confederate States of America. Although he may have underestimated the threat of secession and the prospects for a protracted war, he was at Lincoln’s side every step of the way—playing a direct role, for instance, in the suspension of habeas corpus and the incarceration of suspected spies without trial. He was not an abolitionist—and in that respect he disagreed with his outspoken wife, Frances— but Seward was passionate about preventing the spread of slavery into the western territories. He believed that black Americans should be educated. He did not support fugitive slave laws and even illegally sheltered runaway slaves in his home in Auburn, N.Y.

Seward was a complicated character who stuck to high moral and ethical standards much of the time, but was capable of chicanery, deceit, and maybe even bribery if it would advance what he thought was a worthy purpose.

A world traveler, he was one of Washington’s leading hosts, known for his engaging manner, and yet with his omnipresent cigar and well-worn clothes he appeared to all the world as something akin to an unmade bed. Henry Adams, who admired Seward, described him as “the old fellow with his big nose and his wire hair and grizzled eyebrows and miserable dress” who nevertheless was “rolling out his grand, broad ideas that would inspire a cow with statesmanship if she understood our language.”

Books: “Master of the Mountain”

August 22, 2012

My master’s thesis focused on an aspect of the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson. As a grad student at Penn State, I had access to the stacks at Butler Library in order to do some of the research. That would have been a good thing for a person with singleness of purpose, but not for an undisciplined scholar like me. The route to the “Jo” section of the stacks took me through the “Je” section, where I frequently stopped to browse through the papers of Thomas Jefferson. I have always found his intellect irresistible, and he has had an important influence on my writing. Accordingly, my research in the “Jo” section took a lot longer than it should have.

Jefferson, of course, had his flaws, just as we all do. His biggest one, unfortunately, ruined the lives of hundreds of people over several generations — the people he held in slavery, this herald of equality for “all men.”

That’s the topic of Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves,” a book by Henry Wiencek scheduled for publication in October.

Jefferson, by Wiencek’s account, carefully constructed a society of slaves to do the work at Monticello, Jefferson’s plantation estate in Virginia. Those slaves, like slaves on many other properties in that era, were arranged in a sort of hierarchy based on several factors: Jefferson’s assessment of their potential, the nature of the work they were consigned to, and their relationship to Jefferson. That’s “relationship” in the literal sense, because many of Jefferson’s slaves had a family connection to his wife, Martha. That relationship originated in a liaison between Jefferson’s father-in-law, Thomas Wayles, and one of his slaves, Betty Heming. There were several children born of that relationship and the whole lot, Betty included, became Jefferson’s property when Wayles died. One of those children was Sally Hemings, with whom, Wiencek and many others believe, Jefferson himself was intimate long after Martha Jefferson had died. That subject has gotten a lot of attention in recent years as researchers have tried to determine with certainty whether or not Jefferson fathered children with Sally Hemings. Wiencek presents arguments on both sides but is convinced by the evidence in favor of paternity, including contemporary accounts of household servants bearing a striking resemblance to the lord of the manor himself.

Sexual relationships between masters and slaves were commonplace. If Jefferson and Sally Hemings had such a relationship it would not be nearly so remarkable as the fact that Jefferson owned slaves at all. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Tommy J wrote that. He also publicly denounced slavery and mixed-race sexual relations and argued for emancipation and citizenship for black Americans. He simply didn’t apply those principles to his own life and “property.” Privately he argued — although he knew from the achievements of his own slaves that he was lying — that he didn’t believe black people were capable of participating in a free society, that they were, in fact, little more than imbeciles. He compared them to children. Wiencek writes and documents that Jefferson once even privately speculated that African women had mated with apes. (CP: Mr. Wiencek points out in his comments below that Jefferson made this observation publicly.)

Perhaps Jefferson was trying to make himself feel better about his real motive for keeping people in bondage: profit. He had meticulously calculated what an enslaved human being could generate in income, and it was enough for a long time to allow him to live a privileged life, entertaining a constant train of distinguished guests and satisfying his own thirst for fine French wines, continental cuisine, and rich furnishings.

Jefferson wasn’t the only “founding father” to engage in this behavior. James Monroe, James Madison, and George Washington all kept slaves; Washington freed his only in his will. (CP: This is true but out of context, as Mr. Wiencek explains in his comment below.) It is often written in defense of such men that they had grown up in an atmosphere of slavery and were simply products of their time. That’s an idea that Wiencek debunks, both because Jefferson himself had so often excoriated the institution of slavery and because he had been urged by some of his contemporaries to free his slaves. In fact, Jefferson was upbraided by the Marquis de Lafayette, a hero of the American Revolution, who visited the United States in 1824 and bluntly expressed his disappointment not only that slavery was still in place but that Jefferson himself was still holding people in bondage.

Wiencek also reports that at the request of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who also had participated in the Revolution, Jefferson assisted in the preparation of Kosciuszko’s will in which he left $20,000 with which Jefferson was to buy and free slaves. When Kosciuszko died, Jefferson refused to carry out the will.

Wiencek’s book is a good opportunity to take a close look at how slavery was constituted, how enslaved men, women, and children lived in Virginia in the early 19th century. But its real value is in stripping away the veneer that has been placed over men like Jefferson in an effort to legitimize modern political philosophy through a distorted view of the purity of their motives and personal lives.

Books: “A Slave in the White House”

February 21, 2012

Folks confer a couple of lofty titles on James Madison, but “hypocrite” isn’t usually one of them. But Elizabeth Dowling Taylor isn’t bashful about using that term in her book A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons.

The subject of the book was born into slavery on Montpelier, Madison’s farm in Virginia, and remained in bondage until he was 46 years of age. Within the stifling confines of slavery, Jennings rose to the highest possible place, serving for many years — including the White House years — as Madison’s “body servant.” That meant that he attended to Madison’s personal needs — shaving him, for instance — and traveled with him pretty much everywhere. He also was often the first person a visitor encountered, and he supervised the other household staff in preparing dinners and receptions. Taylor surmises that Jennings, who was literate, paid a lot of attention to the conversations that took place when political and social leaders visited the Madisons.

One of the influential people Jennings became familiar with was Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, who served as a U.S. senator and as secretary of state. Madison had agreed, under pressure from a family member, to provide in his will that his slaves would be freed after specified periods. Madison — whose titles included “Father of the Bill of Rights” — reneged on that commitment and left about 100 slaves to his wife, with the provision that they would not be sold and that they would be freed at some point. When Dolley Madison began selling slaves in order to allay her financial problems, Jennings approached Webster, who had in the past assisted slaves. Webster arranged through a third party for Jennings to buy his freedom; Jennings worked for Webster for several years, and eventually, Webster took on the loan himself.

Jennings was the father of five; he married three times and was widowed twice. When he had satisfied his debt to Webster, he took a job in the Interior Department and worked there until a few years before his death in 1874. During the balance of his working life, he was a bookbinder.

Jennings also seems to have been something of an activist. The evidence Taylor had at her disposal suggested to her that even while he himself was a slave, he forged documents for others trying to get to free states and that after he had achieved his own freedom he was a player in the largest known attempt by slaves to escape to the North — 77 men, women, and children who tried to slip out of Washington via the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay.

The most dramatic incident that occurred during Jennings’ years as a slave probably was the invasion of Washington by British troops in 1814. By Taylor’s account, Jennings was one of the servants at the White House with Dolley Madison when the alarm came that the house had to be evacuated, and he evidently was among the small group that removed the life-sized Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington that now hangs in the East Room. The painting almost certainly would have been destroyed when the British ransacked and burned the mansion.

Taylor’s account of Jennings’ life provides a lot of insight into slavery in Virginia, which was a complex system governed by both necessity and tradition. Her book also explores the contradictory position in which Madison and his close friend, Thomas Jefferson, found themselves. Both men publicly acknowledged that human slavery was essentially evil and that it should be eliminated, but both men kept scores of slaves to labor on their behalf. They were openly berated for this by abolitionists in the United States and by visitors from abroad. The Marquis de Lafayette, for example, visited the United States in 1824 and told Madison and Jefferson that he was nonplussed to find that almost a half century after he had fought for human liberty in the colonies, two of the principal figures of the Revolution were still keeping human beings in bondage.

Madison gave what turned out to be only lip service to emancipation, insisting that while it was desirable, it was also more important to preserve the federal union. Madison also argued that any plan to emancipate slaves had to include a plan to remove them from the United States — probably to west Africa, where none of them had ever lived. His reasoning was that black and white Americans could not live together in peace, and he based that conclusion on his opinion that black people were a depraved race, lazy, profligate, and likely to resort to violence — an idea that apparently was not diluted by his long and close exposure to Paul Jennings, who was none of those things.

Books: “Civil War Wives”

July 6, 2010

When we learn about history, we learn mostly about men. This is something on the question of time. The curriculum in grade school and high school – and even in college for those who aren’t history majors – skims the surface. With respect to many epochs, that means leaving women out of the story, precisely because women were precluded from participating in what went on on the surface. Oh, we got an occasional glimpse of the other half of the population: Cleopatra, Catherine the Great, Queen Victoria, Betsy Ross, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Madame Curie, but the story overall was badly skewed.

This phenomenon is addressed in “Civil War Wives” by Carol Berkin, a book published last year. I read this book because I got it as a Father’s Day gift from one of my daughters — all of whom, by the way, are special women in their own rights, and that has a lot to do with their mother.

Carol Berkin writes about three women who lived through the Civil War period and were directly affected by the war itself and the events and conditions surrounding it. These women were Angelina Grimke Weld, an abolitionist and feminist; Varina Howell Davis, who was married to Confederate President Jefferson Davis; and Julia Dent Grant, who was married to Ulysses S. Grant, Civil War general and postwar president.

I had some knowledge of Varina Davis and Julia Grant before I read this book, but I had not heard of Angelina Grimke Weld, who was an independent thinker from childhood. She was the daughter of a slave-holding plantation owner and judge in South Carolina, but she never accepted the precepts by which her parents lived — including human slavery, self-indulgence, and the notion that women should be happily subordinate to men.

Berkin recounts the process through which Angelina and her sister Sarah moved north and engaged in a prolific campaign against slavery and for women’s rights. Angelina Grimke in the 1830s was arguing for full citizenship for women — up to and including election to the presidency of the United States. (How impatient it must make her, wherever she reposes, to know that the nation still hasn’t chosen a female president.) She was making that argument at a time in which her public appearances, usually with Sarah, were regarded by many people as inappropriate for a woman – particularly when the sisters spoke to audiences of mixed gender and even of mixed race. Angelina married the abolitionist Theodore Weld, and Berkin reports that abolitionist organizations leaned on the husband — who bent a little — to discourage his wife from distracting from the antislavery message by arguing for women’s rights.

When Varina Davis first became engaged to Jefferson Davis, she was 17 years old and he was about twice her age. He had been married many years before, but his first wife died shortly after the wedding, and he may never have fully recovered from that loss. Varina Davis was loyal to her husband while they and their larger family were buffeted by illness, death, financial crises, infidelity, and the many shocks associated with the Civil War. However, theirs was hardly an ideal marriage. Varina was also the daughter of a southern slaveholder, but she was an independent thinker and her thoughts were not always in concert with those of her family or her husband. Jefferson Davis did not admire this trait in his wife, and he admonished her throughout their lives together about her penchant for expressing herself on public matters.

For Varina Davis, one of the most painful episodes of a life full of painful episodes must have been the imprisonment of her husband for two years at Fort Monroe in Phoebus, Virginia. She tirelessly but fruitlessly campaigned to get President Andrew Johnson to intercede on Jefferson Davis’s behalf. She persisted, however, and eventually succeeded not only in getting improved conditions for the prisoner but in getting permission to move into an apartment at the prison herself so that she could visit him regularly.

After the death of Jefferson Davis, Varina shocked southern society by moving north and associating with folks who were anathema in the former Confederacy. One of them was Julia Dent Grant, whose husband had taken compassion on Varina and intervened for the imprisoned Jefferson Davis. Varina also took up a career as a newspaper journalist for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.

Julia Grant was like the other two subjects of this book in that she was also the daughter of a slave-holding planter, but she was quite a different personality. She was a homely girl – and had a crossed eye to boot, but she was never allowed to think of herself as anything but a princess, thanks to a doting father. She was raised in leisure, and she celebrated that fact for the rest of her life. She did exhibit independence with respect to one, critical, point in her life. She persisted in her determination to marry Ulysses S. Grant over the objections of parents who didn’t think the soldier could provide the kind of life Julia wanted and deserved. Ulysses did leave the military after the marriage, but he was not cut out to be a businessman, and he failed repeatedly. His return to arms, of course, led to his greatest successes in life — all of them on the battlefield — and also led to his election to two terms as president, terms that were ridden with scandal, thanks to Grant’s friends and even, in one instance, his brother-in-law.

Julia Grant was spoiled, but she was not petulant, and she weathered the changes in her life brought on by marriage to both an unsuccessful businessman and to a soldier. She reveled in her role as First Lady, and got generally good reviews for her performance as the social leader of the capital. She was not well informed about public affairs, and her occasional attempts to remedy that were not encouraged by her husband, who liked to think of her more as a loving spouse than as a helpmate. One thing was certain, as Berkin emphasizes: Julia and her “Uly” were in love — as much so on the day he died of throat cancer as on the day they were engaged.

Julia Grant, as a widow, was at West Point when she learned that Varina Davis was staying nearby. Julia went to Varina’s room and introduced herself, and the two became friends. It was a suitable gesture for Julia to make, both because Varina had never forgotten the general’s help for her imprisoned husband and because Grant — once the scourge of the South — had left instructions that his casket be carried to its tomb by equal numbers of Union and Confederate generals.

Books: “Franklin Pierce”

June 13, 2010

When I was a kid, a bubble gum company came out with a line of president cards which I guess were intended as the nerd’s alternative to baseball cards. I was into baseball – including the cards – but I was also into history. Also, my Dad owned a grocery store, so I had easy access to whatever the gum companies were peddling.

I recall sitting across from my father at the kitchen table. He held the president cards, arranged in chronological order, and I would try to list them from memory. I can still hear him saying one night when I got stuck somewhere in the latter 19th century: “C’mon! What street does your Aunt Ida live on?” The answer was Garfield Place, as in James A.

It occurred to me at that young age – it was during Dwight Eisenhower’s first administration – that Franklin Pierce had the best-looking face on those cards.

Pierce is the subject of a new little biography – part of a Time Books series on the presidents. This one is written by Michael F. Holt, a history professor at the University of Virginia and an expert on the political life of the country in the years leading up to the Civil War. Sure enough, Holt points out that Pierce was not only handsome, but charming and warm hearted as well. Unfortunately, those qualities carried a lot more weight in the internal politics of Democratic New Hampshire than they did when spread out over a nation that was on the verge of committing suicide over the issue of expanding slavery into the western territories.

In fact, Pierce was nominated for the presidency in 1852 not so much because his party thought he was the Man of the Hour but because the party couldn’t muster a winning vote for any of the three leading candidates – one of whom was not Pierce. He was the original Dark Horse, as far as the presidency of the United States was concerned.

Pierce actually showed some skill in managing the foreign affairs of the country, and he directed the Gadsden Purchase, which was the last major territorial acquisition in what is now the contiguous 48 states. But the crisis of the moment had to do with whether the institution of slavery was going to migrate west along with settlers – an argument that many thought had been closed with the Compromise of 1820. Pierce’s attitude on this issue was complex. First of all, he was a strict constructionist, meaning that he didn’t believe the federal government had any right to interfere in the internal affairs of states, including slavery. Pierce was not pro-slavery per se, but he believed that as long as slavery was protected by the Constitution, the federal government had no right to intrude.

Pierce was also fiercely determined to hold the Union together, and that inspired his loathing of the abolition movement. He considered abolitionists fanatics whose shenanigans were threatening the solidarity of the nation. And so, Pierce was a New Englander who consistently supported the Southern slave-holding oligarchy.

Another error in Pierce’s thinking, Holt explains, was an attempt to unify the Democratic party – which was suffering regional and philosophical tensions – by doling out federal patronage jobs to men who represented the whole spectrum of opinion. Among other things, he appointed his friend Jefferson Davis – soon to be president of the Confederacy – as Secretary of War, a move that did not endear Pierce to northern interests that despised and feared the southern plantation establishment. Rather than unifying the party, this policy succeeded in irritating just about everybody but those who got lucrative or influential positions.

Pierce made enough mistakes that he was denied re-nomination by his own party. He was gracious in defeat, Holt reports, but he had to have been sorely disappointed. Among those who probably was not disappointed at all was the president’s wife, Jane Appleton Pierce, who had no patience with politics or life in the capital. In fact, when a rider caught up with the Pierces’ carriage to report that Pierce had been nominated for president, Jane fainted dead away. The poor woman was shy and fragile, and she and her husband endured a series of tragedies that unfortunately were not uncommon in the mid 19th century. They had three sons. Two died at very young ages and the third was killed when a railroad car in which the parents and child were riding left the track and overturned. Holt mentions that although Pierce did not approve of Abraham Lincoln’s policies, he wrote Lincoln a heartfelt note of sympathy when one of Lincoln’s sons died in the White House.

Pierce was a heavy drinker – a problem drinker, actually – during much of his life, including the years after Jane died in 1863.

An interesting aspect of Pierce’s life was his compassion for other people – the most prominent of whom may have been Nathaniel Hawthorne, whom Pierce met while a student at Bowdoin College. The men were so close that when Hawthorne sensed that he was dying he asked to spend some of his last days with Pierce. Although Hawthorne could travel only with difficulty, Pierce accommodated him and set off with him on a trip that was to be Hawthorne’s last. Pierce found the writer dead in a room at a hotel where the two men had stopped on their journey. Pierce, who was well off, included Hawthorne’s children in his own will.

Pierce is consistently ranked as one of the least effective, or “worst,” of American presidents. But life isn’t lived on historians’ templates; it is lived between the ground and the sky in specific times and places and under specific and complex conditions. Calling a man one of the “worst” in any realm might have as much to do with what we expect of him at a comfortable distance than it has to do with the choices and challenges that confronted that man in his own circumstances. When Abraham Lincoln had been murdered, an angry crowd approached Pierce’s home demanding to know why he wasn’t displaying a flag. Pierce pointed out that his father, Benjamin, had fought in the Revolution, his brothers in the War of 1812, and he himself in the Mexican War: “If the period during which I have served our state and country in various situations, commencing more than thirty-five years ago, have left the question of my devotion to the flag, the Constitution, and the Union in doubt, it is too late now to remove it.”