“I’ll sing in the streets!”

April 2, 2019

An estimated 250,000 people assemble for Tetrazzini’s Christmas Eve concert in San Francisco.

My recent post about Nellie Melba called to mind Luisa Tetrazzini, who had several things in common with Melba. Tetrazzini was also a soprano—a coloratura whose range extended to the F above high C—and a contemporary of Melba at the beginning of the 20th century. Also like Melba, Tetrazzini had an enormously successful career in opera and concert and was treated like royalty around the world. She was, by reputation, a warm and friendly woman, but one of the few people she didn’t get along was Melba.

And Tetrazzini, like Melba, inspired a chef, although there is disagreement about whether the chef was Ernest Arbogast at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco or an unknown practitioner at the Knickerbocker Hotel in New York. The dish involved is “tetrazzini,” which consists of diced chicken or seafood and mushrooms in a sauce of butter, cream, and parmesan, laced with wine or sherry. This is usually served over pasta, although there is no fixed recipe or manner of presentation. Louis Paquet, a chef at the McAlpin Hotel in New York, seems to have had a hand in making this concoction popular. Paquet and Tetrazzini were friends, and he gave her cooking lessons.

And Tetrazzini, like Melba, inspired a chef, although there is disagreement about whether the chef was Ernest Arbogast at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco or an unknown practitioner at the Knickerbocker Hotel in New York. The dish involved is “tetrazzini,” which consists of diced chicken or seafood and mushrooms in a sauce of butter, cream, and parmesan, laced with wine or sherry. This is usually served over pasta, although there is no fixed recipe or manner of presentation. Louis Paquet, a chef at the McAlpin Hotel in New York, seems to have had a hand in making this concoction popular. Paquet and Tetrazzini were friends, and he gave her cooking lessons.

The popularity in their era of artists like Melba and Tetrazzini is hard to imagine now, because media and the nature of celebrity have changed so much. In 1910, Tetrazzini had a contract dispute with the impresario Oscar Hammerstein that was preventing her from singing in opera houses or concert halls in the United States. The soprano, who said San Francisco was her favorite city in the world, said, “When they told me I could not sing in America unless it was for Hammerstein, I said I would sing in the streets of San Francisco, for I knew the streets of San Francisco were free.” And she did that, on Christmas Eve, in front of the San Francisco Chronicle building. The mayor of San Francisco escorted her to a platform that had been built for an orchestra and chorus that were conducted by Paul Steindorf of the city’s Tivoli Opera. Hundreds of thousands of people turned out to hear a concert which Tetrazzini began with “The Last Rose of Summer” and concluded with the massive crowd joining her in “Auld Lang Syne.”

The popularity in their era of artists like Melba and Tetrazzini is hard to imagine now, because media and the nature of celebrity have changed so much. In 1910, Tetrazzini had a contract dispute with the impresario Oscar Hammerstein that was preventing her from singing in opera houses or concert halls in the United States. The soprano, who said San Francisco was her favorite city in the world, said, “When they told me I could not sing in America unless it was for Hammerstein, I said I would sing in the streets of San Francisco, for I knew the streets of San Francisco were free.” And she did that, on Christmas Eve, in front of the San Francisco Chronicle building. The mayor of San Francisco escorted her to a platform that had been built for an orchestra and chorus that were conducted by Paul Steindorf of the city’s Tivoli Opera. Hundreds of thousands of people turned out to hear a concert which Tetrazzini began with “The Last Rose of Summer” and concluded with the massive crowd joining her in “Auld Lang Syne.”

Tetrazzini had several failed marriages, and the last one cost her most of her fortune. When she was through performing, she returned to her native Italy and taught singing in order to support herself. She never lost her joie d’vivre, by all accounts, and used to say, “I’m old. I’m fat. But I’m still Tetrazzini!”

Tetrazzini had several failed marriages, and the last one cost her most of her fortune. When she was through performing, she returned to her native Italy and taught singing in order to support herself. She never lost her joie d’vivre, by all accounts, and used to say, “I’m old. I’m fat. But I’m still Tetrazzini!”

Click HERE to see an unusual film clip in which the 61-year-old Tetrazzini listens to a recording of Enrico Caruso singing “M’appari” from Martha and breaks into a duet with her old friend. Even at this age and with this quality of reproduction, you can get a sense of the character of her voice.

Jack Lawrence: a podiatrist my foot!

April 5, 2017

In my last post, I mentioned Jack Lawrence, who wrote the song “If I Didn’t Care,” which became the signature of The Ink Spots. Their recording of that song in 1939 sold 19 million copies and still ranks as the tenth best-selling single of all time.

Still, that barely scratched the surface where Lawrence was concerned—either professionally or personally. In terms of his profession, consider this:

- “Play, Fiddle, Play,” 1932, which Lawrence wrote when he was 20 years old, became an international hit, a favorite of singers, violinists, and orchestras. It earned Lawrence membership in ASCAP at that young age.

- “All Or Nothing At All,” 1939, with music by Arthur Altman, was Frank Sinatra’s first solo hit.

- “Never Smile at a Crocodile,” 1939, with music by Frank Churchill, became a children’s classic.

- “Yes, My Darling Daughter,” 1940, which Lawrence wrote using music from a Ukrainian folk song, was introduced by Dinah Shore on Eddie Cantor’s radio show, and it was Dinah Shore’s first recording—and a hit.

- “By the Sleepy Lagoon,” 1940, with music written by Eric Coates in 1930, provided hit records for the Harry James Orchestra, Dina Shore, Glenn Miller, Fred Waring and others, including—in 1960—The Platters.

- “Linda,” 1942, which Lawrence wrote during his tour of duty with the Maritime Service during World War II, was published in 1946. The recording in which Buddy Clark sang this song with the Ray Noble Orchestra, was on the Billboard charts for 17 weeks, peaking at No. 1. The title referred to the five-year-old daughter of Lawrence’s attorney, Lee Eastman. Linda Eastman would be known to later generations as Linda McCartney.

- “Heave Ho, My Lads! Heave Ho!” 1943, which Lawrence wrote while he was a bandleader at the Maritime Service Sheepshead Bay Training Center, became the official anthem of the Service and the Merchant Marine.

- “Tenderly,” 1946, with music by Walter Gross, was a hit for Sarah Vaughan in 1947, but went on to become the theme song for Rosemary Clooney.

- “Beyond the Sea,” 1946, with music from Charles Trenet’s “La Mer,” became indelibly associated with Bobby Darin.

- “Hold My Hand,” 1950, which Lawrence wrote with Richard Myers, was used in the 1954 film Susan Slept Here and nominated for an Academy Award as best song.

In later life, Lawrence owned two New York theaters, and his credits as a producer included “Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music” and “Come Back to the Five & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean.”

Lawrence was born in Brooklyn and, although he was already writing songs when he was still a child, he acceded to his parents’ wishes and, after completing high school, received a doctorate in podiatry—a specialty that was not destined to be his career.

Lawrence was gay, and he was the longtime partner of Dr. Walter David Myden, a psychologist and a social worker in Los Angeles. The men met while serving in the Maritime Service. By the 1960s, their relationship was well known in their circles.

Lawrence and Myden were major art collectors and, in 1968, they donated about 100 20th century works to the American Pavilion of Art and Design at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. An interview concerning that donation, published in The New York Times, made no attempt to disguise their relationship—an unusual circumstance at the time but one that Lawrence and Myden could carry off with confidence and dignity. They were major supporters of the Israel Museum, which had just been established. Their donations in 1968 included works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Ben Shahn, John Marin, and Morris Graves.

Myden died suddenly of a heart attack in 1975, but Lawrence lived to the age of 96, dying in 2009 after a fall at his Connecticut home.

‘An unknown artist,’ sad to say

February 9, 2017

I came across an audio file on YouTube that identified the contents as “a very funky version of ‘Water Boy’ by an unknown artist named Valentine Pringle.” Well, unknown to the writer, maybe, but not unknown to me. I spotted Valentine Pringle in 1962 when Harry Belafonte introduced him on “Talent Scouts,” a short-lived television show with a premise that still has traction. Pringle’s voice, which ranged from tenor to basso profundo, was startling in its beauty and its power.

I remembered his name and did everything I could in those pre-internet days to find another opportunity to hear him sing. I was a big consumer of vinyl in those days, and on most Friday nights I would visit Dumont Records in Paterson, New Jersey. Eventually, Val Pringle did show up at Dumont in two RCA LPs–“I Hear America Singing” (1963) and “Powerhouse” (1964). I still have the vinyl, and “Powerhouse” is now available on CD and iTunes.

Pringle made a couple of other recordings; wrote some songs, including “Louise” which he wrote for Belafonte; and had some kind of a career in television and film, but nothing worthy of that voice. The entertainment industry frequently makes no sense to me.

In the 1980s Val Pringle and his wife, Thea van Maastrich, moved to Lesotho, a tiny kingdom that is surrounded by South Africa. Pringle had appeared in Lesotho on a cultural exchange tour sponsored by the United States Information Service, and I guess it appealed to him. He ran a nightclub and the Lancer’s Inn, a hotel and restaurant in Maseru.

On the night of December 13, 1999, two burglars broke into Pringle’s house. Pringle confronted the men with a pistol, but he was stabbed to death. Two men were caught and convicted of the crime.

Pringle had served in the United States Army as a specialist third-class. His ashes are buried in the Arlington National Cemetery.

You can hear Pringle sing in various audio files on line, including “Water Boy” HERE, “Old Man River” HERE, “Take This Hammer” HERE, “The Mouse Song” HERE, and “Oh, Freedom” HERE.

You’ll regret it all one day

January 14, 2016

Among the ads that are “trending” on Facebook lately, on my account at least, is one that is shilling a little pendant with the inscription “You are my sunshine, my only sunshine” with a suggestion that this would be a good gift for one’s grandchildren. I don’t believe I’ll try it on my grandchildren, but the ad reminded me that we used to sing that song when I was in elementary school, and I used to wonder why.

I was puzzled about that because the song is about an adult theme and is rather morbid.

The chorus is a set-up; the first three lines sound cheerful enough, but the last line implies that something is going on that we are not aware of:

You are my sunshine, my only sunshine. / You make me happy when skies are grey. / You’ll never know, dear, how much I love you.

So far, so good, but then the hammer drops:

Please don’t take my sunshine away.

“Whoa,” I used to think when we sang that song. “Where did that come from? What did the songwriter know that we don’t know?”

The combination of the plaintive melody and the sudden implication that catastrophe looms ahead seemed out of place in my Howdy Doody, Lincoln Logs world.

The verses were even more disturbing.

In the first one, we found ourselves singing in our flutey little voices about someone fantasizing about sleeping with a lover.

The other night, dear, as I lay sleeping / I dreamt I held you in my arms.

But any stimulation our young psyches derived from this image was quickly dispelled:

When I awoke, dear, I was mistaken / so I hung my head and cried.

Clearly, we were not dealing with “April Showers” or “Yankee Doodle.” We knew that before we got to the second verse, it’s dark threat:

I will always love you and make you happy / if you will only say the same. / But if you leave me to love another / you will regret it all one day.

It sounds like the last scene of I Pagliacci. The only thing missing is the knife.

The denouement comes in the third verse, and it isn’t pretty:

You told me once dear, you really loved me / and no one else dear, could come between. / But now you’ve left me and love another. / You have shattered all my dreams.

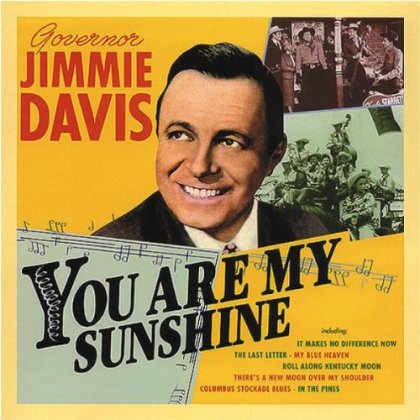

“You Are My Sunshine” was recorded on February 5, 1940 by Jimmy Davis and Charles Mitchell. It is, in fact, the most recent state song of Louisiana, so designated in 1977 by a legislature that apparently hadn’t read the lyrics. I say “the most recent state song” because Louisiana adopted two “official state songs” before this one, and it has at least three other “official songs” for specific purposes. The action in 1977 was based largely on the fact that Jimmy Davis had served as governor of Louisiana from 1960 to 1964.

But before the Davis-Mitchell recording, two other versions of the song were cut in 1939—one by the Pine Ridge Boys (Marvin Taylor and Doug Spivey) on August 22 and one by The Rice Brothers Gang on September 13.

When Davis ran for governor in 1944, he often appeared during his campaign riding on a horse named Sunshine and singing this song.

Although Davis or Davis and Mitchell together are usually given credit for writing the song, it appears that Davis actually bought the rights to it from Paul Rice (of the Rice Brothers). Davis took credit for the tune, but never claimed to have written it.

Although it was an odd choice for us kids, “You Are My Sunshine” played an important in the evolution of American popular music. The Jimmy Davis version was popular enough that it made the country sound attractive to people who normally would have ignored it. In 1940, the song was covered four times, including by cowboy singer Gene Autry, but also by Bing Crosby and Lawrence Welk, so that the crossover occurred almost immediately. Among those who have covered it since then are Nat “King ” Cole, Johnny Cash and June Carter, Ray Charles, Ike and Tina Turner, Aretha Franklin, and Mtume.

“Shine little glow-worm, glimmer, glimmer / Hey, there don’t get dimmer” — Johnny Mercer

August 31, 2015

Johnny Mercer was going for a rhyme. Little did he know that that lyric, which he wrote around 1952, would presage an environmental phenomenon to occur six decades in the future: the vanishing firefly.

We became aware of this on a recent night when we were sitting on our backyard deck after dark, admiring the moon—a natural wonder that has suffered relatively little, so far, from human activity. There is a swath of lawn maybe thirty feet wide between the deck and a thick patch of woods; when we first moved here about 14 years ago, fireflies would flit around in that space on summer nights. As I sat there the other night, I remarked that I hadn’t seen a single firefly this summer. A little research on the iPhone turned up the fact that the firefly population all over the world has been sharply diminished. Those with knowledge of the subject speculate that the factors in this melancholy situation are overdevelopment, which destroys the firefly’s habitat and natural prey; artificial light, which interferes with the mating rituals of fireflies—that’s what those little flashes are all about; and pesticides.

There are some places in the world in which fireflies are so numerous—or have been until now—that they constitute a tourist attraction. I also read about one river in Asia on which they are considered an aid to navigation as their thousands of winking lights along the shore outline the course of the water on dark nights. And, of course, fireflies have been among the charms in the lives of uncounted children.

The firefly was an inspiration to the prominent German composer Paul Lincke, who included a song called “Das Glühwürmchen”—”The Glow Worm”—in his 1902 operetta “Lysistrata.” A lyricist named Lilla Cayley Robinson translated that song into English, and it was used in the 1907 Broadway musical “The Girl Behind the Counter.” But its permanent place in the popular songbook wasn’t sealed until Mercer got a hold of it and put his own spin on it for the Mills Brothers, who recorded it in 1952 as “Glow, Little Glow Worm.” It was the number-one song in the country for three weeks that year, and it was on the charts for twenty-one weeks.

Whoever thought that song might be all we’d have left.

You can see and hear the Mills Brothers sing this song on the “Nat King Cole Show” by clicking The Mills Brothers sing “Glow Worm” .

–

“The song’s gotta come from the heart”

July 24, 2015

Sammy Cahn and Julie Stein wrote six songs for the 1947 movie It Happened in Brooklyn,including “The Song’s Gotta Come from the Heart,” which was performed as a duet by Frank Sinatra and Jimmy Durante. Durante later recorded the song on the RCA Red Seal label with the dramatic soprano Helen Traubel as his partner.

It doesn’t have to be classic or rock / Just as long as it comes from the heart / Just put more heart into you voice / And you’ll become the people’s choice

I thought of that song the other day when my son, Christian, pointed out that Meryl Streep is to star in a movie about Florence Foster Jenkins (1868-1944). Chris wasn’t aware of this, but in 2007 I reviewed a play, Souvenir, by Stephen Temperley, in which Liz McCartney played Mrs. Jenkins and Jim Walton played her accompanist, Cosmé McMoon. There are at least three other plays about her.

Before I saw Souvenir, I had never heard of Mrs. Jenkins, who was born to a wealthy family in Wilkes-Barre and became an accomplished pianist while still a child, even playing at the White House during the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes. When her father refused to finance a European musical education, she eloped and moved to Philadelphia where she taught piano until she injured her arm and, her marriage having ended, was reduced to poverty until her mother came to her assistance.

Around 1900 she and her mother moved to New York City together, and there Mrs. Jenkins entered into another marriage that would last until she died. When her father died in 1908, she inherited enough money to become a prominent Manhattan socialite and to undertake voice lessons. She became even wealthier when her mother died in 1912.

Mrs. Jenkins was under the impression that she was a talented soprano, but the fact was that she couldn’t sing at all. She had no command of tone, pitch, rhythm, or diction. But she continued to study voice, and she gave periodic invitation-only recitals attended by friends who would not have told her the truth. She dressed in elaborate costumes that she had designed herself and engaged in such melodramatic gestures as throwing flower petals to the audience. Because these recitals were private, there were usually no professional critics present. Mrs. Jenkins, who was widely ridiculed, would at times detect laughter during her performance, but she attributed that to the agents of rivals who wanted to discredit her.

When she was 76 years old, Florence Foster Jenkins finally gave a public concert at Carnegie Hall, and tickets sold out weeks in advance. Because it was a public event, critics attended, and they were merciless in their accounts of the performance. Mrs. Jenkins was badly shaken by what was written and said about her; she died of a heart attack two days later, appropriately while shopping for sheet music at G. Schirmer’s music store.

One of the consequences of Mrs. Jenkins’ first marriage was that she contracted syphilis from her husband, a disease for which there was no effective treatment before the discovery of penicillin. The disease itself and the treatments, which commonly employed mercury and arsenic, gradually ravaged her brain and her auditory and central nervous systems.

Temperley’s play, which does not broach the subject of venereal disease, is, on balance, gentle with Mrs. Jenkins. I suspect a movie treatment will more deeply explore the woman’s background. Still, I find myself hoping that the filmmaker will find something sympathetic, if not admirable, about a woman who so doggedly pursued her ambition and didn’t have to die with the regret that comes with never having tried.

Mrs. Jenkins herself summed up what I’m feeling: “People can say I can’t sing, but no one can say I didn’t sing.”

Doing nicely on her own

June 21, 2014

I ordered two CDs from abroad in the past few weeks. One, a collection of Hebrew songs sung by Dudu Fisher, came from Jerusalem; the other, the first solo album by Charlotte Jaconelli, came from Britain. Despite the best of intentions, I haven’t listened to the Dudu Fisher album yet, but I listened to Charlotte Jaconelli’s album with in a couple of hours of receiving it, and I was not disappointed.

Charlotte Jaconelli was half of an act, with Jonathan Antoine, that caused a sensation when they appeared on Britain’s Got Talent in 2012. They were 16 and 17 years old, respectively, and they were an unlikely looking pair, she already cutting a glamorous figure and he very overweight and very casually dressed, with dark wavy hair falling down to his shoulders. There was the usual eye-rolling from Simon Cowell, and the air of resignation as he walked the teens through their bios. But when Jonathan and Charlotte cut loose — he with a startling operatic tenor and she with a pure pop soprano — the house was on its feet.

When the uproar had subsided, the judges were unanimous in their praise, but Cowell, in that delicate way that he has, suggested to Charlotte that she might hold Jonathan back in his career, and told Jonathan that perhaps he should “dump her.” “Well, We came here as a duo,” Jonathan said, “and we’re going to stay here as a duo.” Inexplicably, Jonathan and Charlotte finished the season in second place, behind a dog act, but Cowell signed them to a recording contract and they turned out two albums together. But then they split up because, Charlotte has said, they had different ambitions with respect to the kind of music they want to perform and record. Jonathan’s first solo album is due out in the fall, and Charlotte’s, aptly named Solitaire, was released recently.

There are eleven songs on the CD — an odd number, by the way — and they seem to have been chosen so that on this first solo album, Charlotte can demonstrate her range. She performs pop, Broadway, and classical works, and her pure, silvery voice is equally at ease in all of them. One might detect a little bit of caution in this first solo venture; but, on the other hand, Charlotte also did not give in to any temptation to show off, something she has the vocal power to do. There are two duets (“I Know Him So Well” with Kerry Ellis and “All I Ask of You” with Daniel Koek) that demonstrate again that Charlotte’s voice holds its own with a male counterpart.

I was particularly happy to find that the carefully chosen playlist includes “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls” from the 1843 opera “The Bohemian Girl.” This is a well-traveled song that has been recorded by performers as diverse as Enya and Sinéad O’Connor. Rosina Lawrence dubbed it for Julie Bishop in the 1936 film version of the opera, starring Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. The song has been lampooned at times, but Charlotte Jaconelli’s sensitive performance makes it clear why the tune still has legs after 170 years.

We’re going to be hearing a lot from Charlotte Jaconelli. For now, you can click HERE to see and hear her sing “Pie Jesu,” one of the songs on the Solitaire album.

—

We saw a major production of South Pacific the other night — at least the fifth time we’ve seen it on the stage — and so we heard the Seabees sing once again: “We got mangoes and bananas we can pick right off the tree.” No doubt that was true in that part of the world in the 1940s, but the news lately suggests that bananas may not be nearly that available, if they are available at all.

Aggressive diseases that are immune to pesticides and other control measures are threatening to seriously deplete the world’s banana crop, which provides a staple in the diets of an estimated 420 million people and is an important food source to hundreds of millions of others. The worst menace seems to be a soil fungus known as Panama Disease, which has devastated crops in Southeast Asia and has also been identified in Mozambique and Jordan. Authorities say there is a risk that the fungus will spread to Latin America, where the Cavendish variety of banana most familiar in the United States is grown.

As serious as this situation is, I can’t hear about it without thinking of the novelty song, “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” which was written by Frank Silver and Irving Cohn in 1922 for the Broadway revue “Make it Snappy.” Eddie Cantor sang it in that show. Nonsense songs were very popular then and down through the 1950s, and Billy Jones’s recording of this tune was the number-one song in the nation for five weeks in 1923. The origin of the title and first line of the song is uncertain, but the lyrics as a whole may have been inspired by a similar banana blight that originated in Suriname and by the 1920s reached the Caribbean and Central America.As the illustration on the sheet music suggests, this song was part of a genre of entertainment that depended on making fun of immigrants. The lyric tells of a Greek man who owns a fruit store and answers any question in the same fashion: “Yes, we have no bananas.”

I was curious about a reference in the lyric to “sparrow grass,” a term I had never heard before. I learned that “sparrow grass” is a corruption, perhaps a derisive one, of “asparagus.” The Oxford English Dictionary includes a statement written in 1791 by natural historian John Walker, presumably writing about the usage in Britain: “Sparrow-grass is so general that asparagus has an air of stiffness and pedantry.”

You can hear Billy Jones’s 1923 recording, in which his put-on accent sounds more Italian than Greek, by clicking HERE.

These are the lyrics:

There’s a fruit store on our street

It’s run by a Greek.

And he keeps good things to eat

But you should hear him speak!

When you ask him anything, he never answers “no”.

He just “yes”es you to death,

And as he takes your dough, he tells you…

“Yes! We have no bananas

We have no bananas today!!

We have string beans and onions, cabBAges and scallions

And all kinds of fruit and say

We have an old fashioned toMAHto

A Long Island poTAHto, but

Yes! We have no bananas

We have no bananas today!”

Business got so good for him that he wrote home today,

“Send me Pete and Nick and Jim; I need help right away.”

When he got them in the store, there was fun, you bet.

Someone asked for “sparrow grass”

and then the whole quartet

All answered:

“Yes, we have no bananas

We have-a no bananas today.

Just try those coconuts

Those wall-nuts and doughnuts

There ain’t many nuts like they.

We’ll sell you two kinds of red herring,

Dark brown, and ball-bearing.

But yes, we have no bananas

We have no bananas today.”

Don’t argue with Ralph: The legacy of Redding and Reeves

January 10, 2014

A former newspaper colleague of mine was recalling on Facebook the other day that on the occasion of Kurt Cobain’s suicide an editor approached and asked, in effect, “Is that a big story for your generation?” I know the feeling. In 1967, when I was 25 and Otis Redding was 26, Redding was killed in a plane crash and I had to convince my managing editor that that was front-page news.

The Facebook conversation reminded me of an incident that occurred about 20 years later when my wife and I and another couple were visiting Nevis, a tiny island in the Leeward group in the Caribbean. Shortly after we arrived, a Nevitian fellow we knew only as Ralph was driving us to the house we would be occupying that week. Ralph took us by surprise by asking this question: “Who were the two greatest American singers?” Considering the size of the field, and the fact that we didn’t know the consequences of answering wrong, we kept our counsel. So Ralph answered his own question: “Otis Redding and Jim Reeves.” Discretion being the better part of whaddyacallit, we feebly agreed with that assessment, but Ralph seemed to detect a lack of passion. His voice ticked up a bit in both pitch and volume: “Don’t tell anyone here that Otis Redding and Jim Reeves weren’t the greatest singers!” Having already made mental notes about the ubiquitous machetes on the island, we promised to do no such thing.

I have always enjoyed the fact that one of the songs most identified with Redding, “Try a Little Tenderness,” originated in such an unlikely milieu.That song, a favorite of mine, was written in 1932 by Jimmy Campbell, Reg Connelly, and Harry M. Woods and it was recorded many times, including by such as Jimmy Durante, Frank Sinatra, Mel Tormé, and Frankie Laine, but also by Etta James, Tina Turner, and Three Dog Night. When Otis Redding wanted to record it in his own style in 1966, the publishers were reticent, but that turned out to be the best known and most enduring version. To see and hear Redding singing “Try a Little Tenderness” the day before he died click HERE. To hear a far more conventional rendition by Frank Sinatra, click HERE.

While Ralph’s question in itself took us by surprise, we were even more baffled by the reference to Jim Reeves, who I wouldn’t have expected to hold iconic status in the western Caribbean. Moreover, Reeves had died, also in a plane crash, even earlier than Redding — on July 31, 1964. I had painful memories of that, because I had been a big fan of Jim Reeves, Webb Pierce, Faron Young, Kitty Wells, and that whole crowd. I still have lots of their vinyl and a turntable to play it on.

I don’t know how well known it is, but Reeves was very athletic and had his eye on professional baseball. He played for three years in the St. Louis Cardinals’ farm system before an injury to his sciatic nerve ended his career.

He could hardly have done better in baseball than he did in music; he was an international star. Once he adopted the easygoing Nashville sound, he became one of my favorites. His hits included “Bimbo,” “Welcome to My World,” “Blue Christmas,” and “Make the World Go Away.” I was always stuck on “I Love You Because,” and you can see and hear him singing it at a 1964 concert in Oslo by clicking HERE.