Beyond “the perfect fool”

July 20, 2019

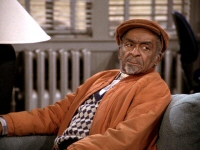

Ed Wynn, Jack Palance, and Keenan Wynn in Requiem for a Heavyweight

I recently came across a pencil drawing of Ed Wynn that I did about 50 years ago. Seeing that drawing was a prompt through which I discovered a pair of events in television broadcasting that combine for a unique and moving experience.

I’m old enough to be familiar with Ed Wynn, because he was frequently on television in the early days of the medium, days that coincided with my childhood. He usually appeared in the persona of “the perfect fool,” wearing a goofy outfit and doing a comedy schtick that made him a big star on the stage, in radio and television, and in film. I was also aware that he had appeared in a dramatic role in Requiem for a Heavyweight, which Rod Serling wrote for television.

ED WYNN

This is the story of a heavyweight boxer, “Mountain” McClintock, played here by Jack Palance, trying to cope with the end of his career in the ring. Ed Wynn’s son Keenan, a successful actor, also appeared in the production in a role closely associated with Ed Wynn’s character—Keenan playing Mache, the boxer’s manager, and Ed playing Army, the boxer’s trainer and cut man. The tension between these two men grows from Army’s conviction that Mache has no sense of Mountain’s humanity and basic decency. That was the first full-length drama broadcast live on television; it appeared on October 11, 1956, when I was 14 years old.

KEENAN WYNN

I don’t remember if I saw that broadcast, but because it was live, I hadn’t seen the performance since—that is, until now. After I came across that drawing of Ed Wynn, I read about his career. I learned that the rehearsals for Requiem for a Heavyweight were a painful experience for Keenan Wynn, because Ed Wynn couldn’t remember his lines or stage directions, and because he would frequently break into his silly laugh while rehearsing serious lines. The program had been promoted in part as the first joint appearance of the famous father and son, so replacing Ed Wynn in the role was problematic.

My drawing of Ed Wynn as “The Perfect Fool”

Ed Wynn seemed lost in the production, even in the dress rehearsal, but when the drama was broadcast on live television, his performance was not only flawless, it was so powerful that it led to several other important dramatic roles for him. In fact, he was nominated for an Oscar for his 1959 performance in The Diary of Anne Frank.

The broadcast of Requiem for a Heavyweight has been preserved; you can watch it by clicking HERE. You’ll notice problems with lighting, sound, and camera angles, but if you pay close attention to Ed Wynn, you’ll see the result of six decades of performing—comedy or not.

But wait. I also learned for the first time of a 1960 Desilu production called The Man in the Funny Suit, which was directed by Ralph Nelson, who also directed the television version of Requiem for a Heavyweight and the motion picture adaptation in 1962, in which Jackie Gleason and Mickey Rooney played the roles originated by Keenan and Ed Wynn.

Keenan Wynn, Ralph Nelson, and Ed Wynn in The Man in the Funny Suit

The Man in the Funny Suit is a dramatization of the actual events involved in Ed Wynn’s performance in Requiem for a Heavyweight. The story portrays Keenan Wynn’s attempt to convince his father that the era of “the perfect fool” had passed, and the son’s embarrassment and frustration over the elder man’s seeming inability to master his first dramatic role. What’s remarkable about this production is that Ed and Keenan Wynn play themselves, a brave and honest decision that would have been out of the reach of lesser men. Also playing themselves are Rod Serling, former world boxing champion Max Rosenbloom, Ralph Nelson, and—in a straight role—Red Skelton. You can watch this program by clicking HERE.

Viewing these two productions—in their chronological order—is a rare opportunity to see inside the relationship between a famous father and son. I, for one, an grateful for the self-confidence and generosity of heart, on the part of both men, that made this possible.

As the World Turned

July 3, 2014

The death this week of Bob Hastings, the popular and ubiquitous character actor, reminded me that it has been just over 33 years since I passed some time with his brother, Don.

Somewhere in the genetic makeup of these siblings was a trait for longevity, and not only because Bob Hastings was 89 when he died on Monday, and Don Hastings, who lives in upstate New York, is 80. No, it’s their professional longevity that is remarkable. Bob Hastings was an actor for 77 years, and Don has been at it for 74 years. Almost all of their cumulative experience has been in television. As has been reported widely in days since his death, Bob became familiar to millions through his regular appearances on such shows as Sergeant Bilko, McHale’s Navy, General Hospital, and All in the Family.

Both brothers began their performing careers on a radio show, Coast to Coast on a Bus.

I first became aware of Don Hastings when I was seven years old and television’s first science-fiction series, Captain Video and his Video Ranger made its debut on the DuMont Network, which broadcast on Channel 5 in New York. Don, who was about 15 years old at the time, played the Video Ranger for the entire five-year run of the show, which ended in 1955. Captain Video was played first by Richard Coogan and then by Al Hodge. DuMont was the weak sister among the television networks at that time, and Captain Video ran on a very low budget. In fact, Don Hastings told me that the weekly budget for props and scenery was $15: “Anything we could get from the shop and paint to look like something else, we used.”

The production quality of this show was, perhaps, laughable even by the standards of other networks at that time. Still, it was an adventure, and an important one at that. Captain Video was broadcast live, at first six days a week and then five. There were no do-overs, there was no editing, what you saw was what you got. And that, as any actor who worked in early television will tell you, was exciting. Don Hastings, who had a long career in the far more sophisticated medium that television became, thinks well of his experience as a legitimate television pioneer: “It was more fun. The whole attitude was different. Big business wasn’t really with us then.”

“After Captain Video,” Don told me in 1981, “I didn’t do a television show for four months, and that’s the longest period I’ve had in my life when I didn’t work.. It was good for my golf but bad for everything else.” He made up for it, though. From 1956 to 1960, he played Jack Lane on the daytime drama The Edge of Night and from 1960 until 2010, he played Dr. Robert Hughes on As the World Turns. He had the last line spoken on that show when it went off the air: “Good night.”

As well known as Don Hastings became with all that exposure on national television, he told me that he experienced a different kind of fame than what a Hollywood actor or a sit-com star might experience, something unique to soap opera figures. “People treat us like people they know,” he said. “I don’t mean we’re celebrities to them; we’re people they recognize and know. If you’re recognized, it’s not going to ruin your dinner.”

I felt at the time that Hastings might be comfortable with that sort of relationship with fans, because he is soft-spoken and well mannered and, as I learned first-hand, a consummate professional. While I was waiting for a lunch date with Don Hastings, I watched from the control room the taping of an episode of As the World Turns. Something went wrong with a scene, and it had to be re-shot. During the brief pause, Hastings, whom we could see on the monitors, made a wisecrack, but he did it in character, as Dr. Bob Hughes. One of the technicians said to a colleague, “Now there is a guy who can have fun while he’s working without acting like an amateur.”

“Oh, no, it isn’t the trees . . . .”

September 23, 2013

I was about to watch an episode of the Jack Benny Program recently when I became absorbed in the opening theme. The theme is associated not just with the television series but with Jack Benny himself. The song, “Love in Bloom,” was not written by amateurs. The music was by Ralph Rainger and the lyrics by Leo Robin. Ralph Rainger, a member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame, wrote a lot of music for movies between 1930 and 1942. One of his compositions, “Thanks for the Memory,” written for The Big Broadcast of 1938, won an Academy Award. (I’ll have more to say about that song in a later post.) Leo Robin, who wrote the lyrics to “Love in Bloom,” is also a member of the Hall of Fame. His work included “Thanks for the Memory,” “Beyond the Blue Horizon,” “Prisoner of Love,” and “Blue Hawaii.”

“Love in Bloom” was introduced in 1934 in the film She Loves Me Not. It was sung in a duet by Bing Crosby and Kitty Carlisle.

Crosby, that same year, was the first to record the song, which was nominated for an Academy Award.

Kitty Carlisle — an elegant woman whom, incidentally, I once visited at her Manhattan apartment — liked the song enough that she considered adopting it as her own theme. She scuttled that idea, however, when Benny made the song his signature, frequently playing it, and deliberately butchering it, on his violin.

The song has qualities that don’t come across in most of Benny’s renditions. You can see for yourself as Crosby and Kitty Carlisle sing it in the film. Click HERE.

You can also see a hiliarious routine in which Benny and Liberace play the song on the keyboard and violin on a 1969 episode of Liberace’s TV show. Here Benny lets himself show, for a while at least, that he was more competent on the violin than he cared to admit. Click HERE.

Netflix Update No. 80: “The Jack Benny Show”

August 22, 2013

My lack of interest in current television is at the point where I have a very limited diet. I’m not going to make an argument for the “golden age,” because I don’t think it’s valid. There have been many excellent shows since the 1950s. Still — and I’m willing to call this a matter of taste — I am attracted to early programming, and especially to situation comedies such as Make Room for Daddy, Burns and Allen, and the proto-sitcom, The Goldbergs.

Thank heaven, then, for services like Netflix, which makes many of these shows available, including The Jack Benny Show. Benny is a favorite of mine, not only because he was such a unique character and was so skillful in portraying his fictional persona — the miser who wouldn’t admit to being older than 39 — but because of his place in American show business history.

A poster advertises a broadcast of Jack Benny’s radio show on a station in Seattle. LSMFT, for the benefit of the younger crowd, stood for “Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco.”

The production values of television shows in the 1950s do not compare favorably with what we have become used to sixty years later, but the era got its “golden age” reputation because of the cadre of writers and performers who had migrated to television on a path that led from vaudeville, burlesque, and the legitimate theater by way of radio. Jack Benny and many of his contemporaries had worked very hard to develop their sense of what audiences at the time thought was funny or dramatic, and to develop the timing and delivery that would work in the new medium. They learned their lessons well; Jack Benny’s slow burn is still funny, even when you can see it coming from a mile away.

An interesting aspect of Benny’s show was his relationship with Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, a gravel-voiced black actor who was part of the Benny stock company which included, among others, announcer Don Wilson and Irish crooner Dennis Day.

Anderson who, like Benny, got his start in vaudeville, started working with Benny in radio in 1937, first in a few bit parts and then playing Benny’s valet. He played that role on radio and television until 1965. He was the first black performer to have a regular role on radio, but that meant that he was faced with what became a classic conundrum for black artists — the question of whether to play a subservient character or not work in movies, radio, or TV. It was a difficult question for the actors as well as for the black Americans who were being treated as second-class citizens if as citizens at all.

Given the racial climate at the time, The Jack Benny Show took an unusual approach by presenting Rochester as a quick-witted and sarcastic character who was always a little smarter than his boss. The approach was unusual also because this plot element juxtaposed two deadpan figures and the combination was hilarious and was sustained for nearly thirty years. At first, in radio, there was often a racial aspect to the humor surrounding Rochester, but after World War II, Benny — who took an unambiguous public stand in favor of racial harmony — insisted that all racial content be eliminated from his scripts.

Eddie Anderson was one of the most popular and highest-paid actors of his time. He appeared in many movies, including Green Pastures and Gone With the Wind. He handled his money wisely and was both wealthy and generous. Among other enterprises, he owned a company that manufactured parachutes for the American military during World War II.

You can see Jack Benny and Eddie Anderson in a typically funny scene by clicking here.

“We are all brothers. . . .”

May 4, 2012

I gather from schnibles I’ve seen on the Internet that 30 Rock caught some flack for a parody of the 1950s television series Amos ‘n’ Andy. In the 30 Rock sketch, which was called Alfie and Abner, the characters were played by Tracy Morgan and John Hamm, who was in black face and an Afro wig, an image some folks found offensive. Somewhat incongruously — not to put too fine a point on it — the set was a replica of the Kramdens’ Bensonhurst kitchen rather than the most frequent Harlem scenes on Amos ‘n’ Andy — the Mystic Knights of the Sea lodge hall and the apartment of George and Sapphire Stevens.

The premise of the 30 Rock sketch was that one actor was in black face because NBC thought it would be too big a step to have two black actors on the stage at the same time. The irony is that Amos ‘n’ Andy, which had its original run from 1951 to 1953, was the first television series to have virtually an all black cast. White actors appeared in incidental roles in only a handful of episodes. I think it’s fairly well known that the show was driven out of production because of objections — most prominently from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People — on the grounds that it presented negative stereotypes of black Americans. It continued in reruns on some stations into the 1960s.

The television series evolved from a radio series that ran from 1928 until 1960. At the height of its success, Amos ‘n’ Andy was not only the most popular radio show on the air but the most popular diversion of any kind. And yet that series featured white actors mimicking black characters — namely Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, who created the show. For a while, Gosden and Correll performed all the male roles and some of the females. Later, other actors and actresses were cast in the supporting parts while Gosden and Correll continued to play the principal figures: Amos Jones, Andrew H. Brown, and George “Kingfish” Stevens. Gosden and Correll went a step further in the 1930 RKO movie “Check and Double Check,” donning black face to play Amos (Gosden) and Andy (Correll). Duke Ellington and his orchestra appeared in that movie.

The TV series is now controlled by CBS, which has withdrawn it from circulation and has at times taken legal action in an attempt to squelch the widespread Internet sale of bootleg tapes and DVDs of the episodes.

The Amos ‘n’ Andy television show is in a unique position, I think, in the sense that if it were judged in a vacuum — with no reference to who created it and when it first appeared — the conclusion might be different than it is when the show is viewed in its historical context. It was introduced when black American citizens in large numbers were still being denied their civil rights, when black people in many parts of the country were regularly threatened with violence, and when black people were freely lampooned in movies, cartoons, and minstrels. The show was still being broadcast in syndication in 1955, when Sarah Louise Keys, Claudette Colvin, and Rosa Parks in turn refused to give up their seats on the Montgomery, Alabama bus system to make way for white passengers. With Jim Crow making his last stand against legal equality and common decency, it shouldn’t have been surprising that black society and others would object to some of the characterizations on Amos ‘n’ Andy.

I have owned copies of all 78 known episodes of the series for many years, and I have watched them all several times and assigned students to write about them. I have also done a lot of research about the show itself and about the actors who appeared in it, and I have interviewed several people who were connected to it, including Nick Stewart who played Lightnin’ — the janitor at the lodge hall. Based on all that exposure, I think one can at least make the argument that, taken out of its milieu, Amos ‘n’ Andy would be no more offensive than all-black sitcoms that have appeared since, including Sandford and Son and Family Matters.

In fact, Amos ‘n’ Andy is fashioned on the same model as The Honeymooners. The rap on Amos ‘n’ Andy has been that it perpetuates stereotypes of black men as lazy, shiftless, and dumb, and of black women as shrewish and unattractive. As for the men, those characterizations apply to only four characters in the series: Andy Brown (Spencer Williams Jr.), George “Kingfish Stevens (Tim Moore), Lightnin’ (Nick Stewart, billed as Nick O’Deamus), and the lawyer Algonquin J. Calhoun (Johnny Lee).

These men live in a universe in which virtually everyone is black and, significantly, in which everybody but them is dignified, moral, and responsible. Just as The Honeymooners didn’t imply that all white men were naive schemers like Ralph Kramden or good-natured dumbbells like Ed Norton, Amos ‘n’ Andy didn’t imply that all black men were lummoxes, wasters, or charlatans. In both cases, the point was that the main characters were out of step with everyone around them; they were the exceptions, not the rules.

The most prominent female character on Amos ‘n’ Andy was Sapphire Stevens, the Kingfish’s wife. Sapphire was played by Ernestine Wade, who actually was a pretty woman. Sapphire longed for a more genteel life in which she wasn’t hounded by bill collectors and in which she could associate with folks a little more erudite and stimulating than Andy Brown. Wade portrayed her as a decent woman who was faithful to a husband who didn’t deserve it; if Sapphire nagged the Kingfish and at times lost her temper with him, no one could blame her any more than they could blame Alice Kramden from blowing up at Ralph.

Less sympathetic a character, perhaps, was Ramona Smith, Sapphire’s mother, who was presented as the classic bellicose battleship of a mother-in-law — an accessory the Kingfish had in common with Ralph Kramden.

The broadest of the regular characters were the shambling, drawling Lightnin’, and Calhoun, a loudmouth and a fake.

There was a shift in emphasis in the television series in which Amos, although a title character and often the voice that introduced the episode (“Hello, folks. This is Amos. . . .”), became a secondary figure, and the Kingfish became the focal point of almost every episode. In the TV series, Amos was a level-headed, intelligent, soft-spoken, man who owned his own taxicab and led a quiet life with his lovely wife, Ruby, and their two daughters. Amos was often the Jiminy Cricket to the Kingfish and Andy, giving them sound advice and sometimes directly getting them out of trouble.

An aspect of this show that is always overlooked is the quality of the cast it brought together. Many of the actors had long careers as entertainers, persisting through an era in which they were unappreciated, type cast, and often rudely treated.

Tim Moore, who played the chronically unemployed and finagling Kingfish, had a remarkable life as a vaudevillian, entertaining all over the world. He also appeared in several Broadway shows and in films. He was even fairly successful as a boxer. He was lured out of retirement to play the role in Amos ‘n’ Andy. His character’s sobriquet was actually his title as head of the lodge — the kingfish. When he wanted his pals to bail him out of some scrape, he often reminded them, “After all, we are all brothers in that great organization, the Mystic Knights of the Sea.”

Spencer Williams Jr., who played the sweet but gullible oaf Andy Brown, was an important figure in the history of American film. A World War I army veteran who worked in many aspects of the movie business, including as a sound technician, eventually became a writer, director, and producer of so-called “race movies,” films that were made specifically to be shown in segregated theaters. His film “Go Down Jesus,” which was made on a $5,000 budget and with nonprofessional actors, was one of the most successful “race films” of all time. Time magazine called it one of the “25 most important films on race.”

Alvin Childress, who played the sensible and gentle Amos Jones, held a bachelor’s degree in sociology. He began working as an actor with a Harlem theater company, and he worked on both the stage and on film. He appeared on Broadway as Noah in Philip Yordan’s play Anna Lucasta, which ran for 957 performances. Although he appeared in a couple movies and in episodes of Perry Mason, Sandford and Son, Good Times, and The Jeffersons, Childress, who felt he had been typed by casting directors as Amos Jones, had a hard time sustaining his career. His first marriage, which lasted for 23 years, was to a well known writer and actress, Alice (Herndon) Childress.

Nick Stewart, who played Lightnin’, was a dancer and comedian who appeared in night clubs, Broadway shows, films, and radio. Stewart was the voice of Br’er Bear in the 1946 Disney movie Song of the South. In 1950, He and his wife, Edna, founded the Ebony Showcase Theater in Los Angeles, where for many years they provided a venue in which black actors could appear in quality productions.

Johnny Lee, who played the blustering, incompetent lawyer, Algonquin J. Calhoun, was a dancer and actor who appeared in a couple of dozen films and television shows, perhaps most notably as the voice of Br’er Rabbit in Song of the South. He had featured roles in Come On, Cowboy! (1948) and She’s Too Mean for Me (1948) and he played a stuttering bill collector in Boarding House Blues (1948). He also starred in an all-black musical comedy, Sugar Hill, at the Las Palmas Theatre in Hollywood in 1949. His last TV role was Mr. Gibbons the Locksmith on Dennis the Menace in 1963.

In addition to these regular players, Amos ‘n Andy provided occasional roles for some very talented actors, including the sisters Amanda and Lillian Randolph. Amanda Randolph, who played Ramona Smith, mother of Sapphire Stevens, was the first black actress to appear on a regularly-scheduled network television show. That was The Laytons, which appeared on the old Dumont network for two months in 1948. She was an exceptional jazz pianist and a composer. She appeared in New York musicals, entertained in Europe, performed in vaudeville, and cut records as both a musician and a vocalist. She appeared on Broadway, in films, and on radio. On radio, she played the title role in Beulah in the 1953-1954 season, inheriting the role from Lillian.

She was the first black American actress to have her own daytime network TV show — Amanda, which ran on Dumont in the 1948-49 season. Among her many TV roles was Louise, the wisecracking maid on Danny Thomas’s comedy series.

Lillian Randolph, who appeared in Amos ‘n’ Andy as Madame Queen, a former girlfriend of Andy Brown, was also a multi-talented performer on radio, television, and film. She had played Madame Queen on the radio, too, and made the character’s name a household word in the United States. She played the maid Birdie Lee Coggins in The Great Gildersleeve radio series, and she repeated the role in Gildersleeve films and the later TV series. Her performance of a gospel song on the TV series led to a gospel album on Dootone Records. She also made regular appearances on The Baby Snooks Show and The Billie Burke Show on radio. Her best known film roles probably were Annie in It’s a Wonderful Life and Bessie in The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer. Her television roles included Bill Cosby’s mother on The Bill Cosby Show, and Red Foxx’s aunt Esther on Sandford and Son. Altogether, she appeared in about 93 movie and television properties. In 1954, Lillian Randolph became the first black member of the board of directors of the Hollywood Chapter of the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.

One of the most eminent persons to appear on the Amos ‘n’ Andy TV series was Jester Hairston, who made occasional appearances as both Sapphire’s brother Leroy and as wealthy and dapper lodge member Henry Van Porter. Although he appeared in about 20 films and several TV shows, acting was secondary to Hairston’s career as a composer, songwriter, arranger, and choral conductor. He wrote the song “Amen” for the 1963 film Lilies of the Field and he dubbed the song for Sidney Poitier to lip-sync. He also wrote the Christmas carol Mary’s Little Boy Child. Harry Belafonte’s recording of the song reached No. 1 on the charts in the UK in 1957. From 1986 to 1991, Hairston played Rolly Forbes in the TV series Amen.

Hairston was a graduate of Tufts University, and he studied music at the Julliard School. He was highly regarded as a conductor of choirs, including on Broadway, and as a composer and arranger of choral music. In 1985, when few foreign performers were appearing in China, he took a multi-racial choir to tour the country. Hairston was a founder of the Screen Actors Guild.

Also among the actors who appeared on Amos ‘n’ Andy was Roy Glenn, who had a rich baritone-bass voice that he got to use in one episode, singing some lines from “Red Sails in the Sunset.” Glenn had a long acting career, appearing in 96 films and television shows. His most prominent role probably was Sidney Poitier’s father in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967).

The only Amos ‘n’ Andy alumnus I’m aware of who not only is still living but has worked as an actor recently is Jay Brooks, who appeared in two episodes of Seinfeld, as Sid, the man who provides a service in Jerry Seinfeld’s neighborhood by moving cars from one side of the street to the other to comply with New York City’s alternate-side parking regulations.

The actors who appeared on Amos ‘n’ Andy were often criticized for accepting roles on a show that some people felt was demeaning to black people. More often than not, the roles offered to black performers in those days in any venue were stereotyped if they weren’t out-and-out offensive. Some of the actors — Alvin Childress, for example — argued that they had to work where they could and that by accepting parts on the first all-black show on television, they had paved the way for others to follow. It’s too late to resolve that question but, taken on its own merits, Amos ‘n’ Andy was a funny show, due in large part to the performances of a lot of experienced actors who, over their careers, made enormous contributions to American popular culture. They don’t deserve to be forgotten.

Where have you gone, Carmen Miranda?

April 21, 2011

The allusion to Carmen Miranda on this week’s episode of “Modern Family” got us to thinking about her for the first time in recent memory. Our first reaction was to wonder how many people in, say, their 40s or less who were watching that show would have known who Carmen Miranda was. When she was in her heyday, there was no need to ask; she was very popular — with good reason — and she was very successful.

The allusion to Carmen Miranda on this week’s episode of “Modern Family” got us to thinking about her for the first time in recent memory. Our first reaction was to wonder how many people in, say, their 40s or less who were watching that show would have known who Carmen Miranda was. When she was in her heyday, there was no need to ask; she was very popular — with good reason — and she was very successful. Carmen Miranda was born in Portugal in 1909, but she grew up in Brazil. She began performing at an early age, although financial stresses on her family led her to a short-lived but profitable career as a milliner. She continued to pursue her musical career, though, and before she came to the United States in 1939, she was already established as a star on radio, recordings, and film. She ultimately made 14 Hollywood movies and at one point was the highest-paid woman in the industry. She also made occasional appearances in the variety-show format that was a staple in early American television.

Carmen Miranda was born in Portugal in 1909, but she grew up in Brazil. She began performing at an early age, although financial stresses on her family led her to a short-lived but profitable career as a milliner. She continued to pursue her musical career, though, and before she came to the United States in 1939, she was already established as a star on radio, recordings, and film. She ultimately made 14 Hollywood movies and at one point was the highest-paid woman in the industry. She also made occasional appearances in the variety-show format that was a staple in early American television. Carmen Miranda was subject to some criticism in Brazil during her lifetime on the grounds that she had become too Americanized and was presenting an inaccurate image of Brazilian culture. She was so upset by this evaluation of her work that she stayed away from Brazil for many years. Now, however, she is memorialized by museums in both Brazil and Portugal. She is also the namesake of Carmen Miranda Square at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Orange Drive, across from Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

Carmen Miranda was subject to some criticism in Brazil during her lifetime on the grounds that she had become too Americanized and was presenting an inaccurate image of Brazilian culture. She was so upset by this evaluation of her work that she stayed away from Brazil for many years. Now, however, she is memorialized by museums in both Brazil and Portugal. She is also the namesake of Carmen Miranda Square at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Orange Drive, across from Grauman’s Chinese Theater.I’d know that voice anywhere

July 10, 2010

Somewhere, within the past few days, I saw the name “Ken Lynch.” It almost has to have been in the credits of a movie or TV show I was watching, but I can’t remember. Maybe I was dozing off at the time. It would not be unusual for me to have seen his name, because he appeared in about 175 television shows and movies — mostly TV. He frequently played a tough cop.

His name is not a household word, but I have been aware of him at least since I was 12 years old. I can recall that, because from 1949 to 1954 he had the title role in a detective series called “The Plainclothesman,” which was broadcast on the old Dumont network. I don’t remember when I started watching that show, but it could have been at the beginning, when I was 7, because Dad bought our first TV at Izzy Kaufman’s appliance store in ’49.

Television was new, and we had no context for it, so almost anything we saw was mesmerizing. I believe this cop show was especially so because of its unusual approach – namely, that the title character, known only as “the lieutenant,” never appeared on camera. The viewer, in effect, saw the story through the eyes of the lieutenant. Parenthetically — I suppose I could have just used parentheses — Dumont also had a detective series that ran from 1950 to 1954 in which one of the characters didn’t appear on camera. That series, which was broadcast live, was “Rocky King: Detective,” starring Roscoe Karns. At the end of each episode, Rocky King would talk on the telephone to his wife, Mabel, played by Grace Carney. Viewers would hear Mabel’s voice, but never see her face. Each show ended when Rocky hung up the phone and said, “Great girl, that Mabel!”

Possibly because the only impression I had of Ken Lynch was his distinctive raspy voice, I recognized it when I was watching an episode of “The Honeymooners,” a show that was very stingy about giving credit to actors other than the four stars. This occurred only a year or two after “The Plainclothesman” went off the air, but as sure as I was that we had finally seen “the lieutenant,” I couldn’t confirm it until much more recently.

In that episode, Ralph Kramden (Jackie Gleason) witnesses an armed robbery while playing pool with his sidekick, Ed Norton, and is afraid to tell police what he saw, because the robbers might retaliate. A detective comes to the Kramden apartment to question Ralph, and that detective is played by Ken Lynch. His voice, when he tells Ralph, “If you’re not a witness, you’re not entitled to police protection. And thanks — for nothin’!” is Lynch’s unmistakable file-on-metal sound.

Having no better way to exercise my brain cells, I wondered about that for decades. It was only the advent of the Internet and its seemingly inexhaustible resources that I was able to confirm that the invisible “lieutenant” was the visible cop in Bensonhurst.

Ken Lynch was born in Cleveland in 1910, and he died in Burbank in 1990. Oddly, despite his prolific career, Wikipedia doesn’t have an English language article on him, although there is one in French, but with no real biographical information. There is a short and descriptive profile of him on the International Movie Database web site, at THIS LINK.

“You sing a bingo bango bingo” — Tom Glazer

October 27, 2009

During the last ALCS game, I got this lyric stuck in my head: “So who would want these diamond gems? / They’re diamonds in the rough. / A baseball team needs nine good men. / One guy just ain’t enough.”

During the last ALCS game, I got this lyric stuck in my head: “So who would want these diamond gems? / They’re diamonds in the rough. / A baseball team needs nine good men. / One guy just ain’t enough.”

I remember hearing that on television about 50 years ago. It was sung to the tune of “Yankee Doodle,” and it got stuck in my head. Every once in a while it comes to the surface.

When it came to the surface the other day, I decided to do what I always tell my students to do — look it up. In the Internet age, that’s a lot easier than it used to be, although this song seemed so obscure that I didn’t expect to track it down.

By searching on a phrase from that lyric I actually found one reference to it. It turns out that it’s part of a jingle that was used in one of a series of public service announcements sponsored by the American Jewish Committee. An application for a grant to help fund the series turned up on a site that houses the archives of the AJC. Among the documents was a page from an issue of TV Guide dated April 28, 1951. On the page was a short article about this animated short that was part of a larger, award-winning anti-bigotry campaign by the AJC. The short was designed to reinforce the idea that people of many backgrounds contributed to life in the United States.

By searching on a phrase from that lyric I actually found one reference to it. It turns out that it’s part of a jingle that was used in one of a series of public service announcements sponsored by the American Jewish Committee. An application for a grant to help fund the series turned up on a site that houses the archives of the AJC. Among the documents was a page from an issue of TV Guide dated April 28, 1951. On the page was a short article about this animated short that was part of a larger, award-winning anti-bigotry campaign by the AJC. The short was designed to reinforce the idea that people of many backgrounds contributed to life in the United States.

The animated cartoons were by Fred Arnott and the song was written by Lynn Rhodes. I could find out nothing more about either of them. However, the song was sung by Tom Glazer, who had a decent reputation as a folk singer. A lot of people of a certain generation will remember his novelty song “On Top of Spaghetti,” a children’s song he recorded in 1963. He also wrote “Because All Men Are Brothers,” which was recorded by the Weavers and by Peter Paul, and Mary, and “Talkin’ Inflation Blues,” which was recorded by Bob Dylan. Glazer wrote idiotic and kind of racist lyrics to “Skokian,” a Zimbabwean song that was popular in multiple versions. Glazer’s version was recorded by the Four Lads.

The animated cartoons were by Fred Arnott and the song was written by Lynn Rhodes. I could find out nothing more about either of them. However, the song was sung by Tom Glazer, who had a decent reputation as a folk singer. A lot of people of a certain generation will remember his novelty song “On Top of Spaghetti,” a children’s song he recorded in 1963. He also wrote “Because All Men Are Brothers,” which was recorded by the Weavers and by Peter Paul, and Mary, and “Talkin’ Inflation Blues,” which was recorded by Bob Dylan. Glazer wrote idiotic and kind of racist lyrics to “Skokian,” a Zimbabwean song that was popular in multiple versions. Glazer’s version was recorded by the Four Lads.

Anyway, the song he sang for the AJC went like this:

Though every player is top flight / Our team just falls to pieces / With every game they have to play / The number of flubs increases.

To figure why they fall apart / You needn’t be too clever / With no teamwork the team’s big star / Will die on third forever.

The shortstop simply cannot play / With the jerk who’s second sacker / The pitcher can pitch to anyone / But certainly not to his catcher.

So who would want these diamond gems? ‘/ They’re diamonds in the rough / A baseball team needs nine good men / One guy just ain’t enough.

A nation’s like a baseball team / It’s run by teamwork too. / And every race and every creed / Works with Y-O-U.

Play ball with all your neighbors / Pitch in a little more / Americans, join your teammates all / Roll up a winning score.