“We are all brothers. . . .”

May 4, 2012

I gather from schnibles I’ve seen on the Internet that 30 Rock caught some flack for a parody of the 1950s television series Amos ‘n’ Andy. In the 30 Rock sketch, which was called Alfie and Abner, the characters were played by Tracy Morgan and John Hamm, who was in black face and an Afro wig, an image some folks found offensive. Somewhat incongruously — not to put too fine a point on it — the set was a replica of the Kramdens’ Bensonhurst kitchen rather than the most frequent Harlem scenes on Amos ‘n’ Andy — the Mystic Knights of the Sea lodge hall and the apartment of George and Sapphire Stevens.

The premise of the 30 Rock sketch was that one actor was in black face because NBC thought it would be too big a step to have two black actors on the stage at the same time. The irony is that Amos ‘n’ Andy, which had its original run from 1951 to 1953, was the first television series to have virtually an all black cast. White actors appeared in incidental roles in only a handful of episodes. I think it’s fairly well known that the show was driven out of production because of objections — most prominently from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People — on the grounds that it presented negative stereotypes of black Americans. It continued in reruns on some stations into the 1960s.

The television series evolved from a radio series that ran from 1928 until 1960. At the height of its success, Amos ‘n’ Andy was not only the most popular radio show on the air but the most popular diversion of any kind. And yet that series featured white actors mimicking black characters — namely Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, who created the show. For a while, Gosden and Correll performed all the male roles and some of the females. Later, other actors and actresses were cast in the supporting parts while Gosden and Correll continued to play the principal figures: Amos Jones, Andrew H. Brown, and George “Kingfish” Stevens. Gosden and Correll went a step further in the 1930 RKO movie “Check and Double Check,” donning black face to play Amos (Gosden) and Andy (Correll). Duke Ellington and his orchestra appeared in that movie.

The TV series is now controlled by CBS, which has withdrawn it from circulation and has at times taken legal action in an attempt to squelch the widespread Internet sale of bootleg tapes and DVDs of the episodes.

The Amos ‘n’ Andy television show is in a unique position, I think, in the sense that if it were judged in a vacuum — with no reference to who created it and when it first appeared — the conclusion might be different than it is when the show is viewed in its historical context. It was introduced when black American citizens in large numbers were still being denied their civil rights, when black people in many parts of the country were regularly threatened with violence, and when black people were freely lampooned in movies, cartoons, and minstrels. The show was still being broadcast in syndication in 1955, when Sarah Louise Keys, Claudette Colvin, and Rosa Parks in turn refused to give up their seats on the Montgomery, Alabama bus system to make way for white passengers. With Jim Crow making his last stand against legal equality and common decency, it shouldn’t have been surprising that black society and others would object to some of the characterizations on Amos ‘n’ Andy.

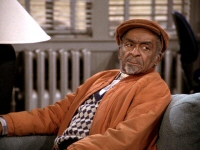

I have owned copies of all 78 known episodes of the series for many years, and I have watched them all several times and assigned students to write about them. I have also done a lot of research about the show itself and about the actors who appeared in it, and I have interviewed several people who were connected to it, including Nick Stewart who played Lightnin’ — the janitor at the lodge hall. Based on all that exposure, I think one can at least make the argument that, taken out of its milieu, Amos ‘n’ Andy would be no more offensive than all-black sitcoms that have appeared since, including Sandford and Son and Family Matters.

In fact, Amos ‘n’ Andy is fashioned on the same model as The Honeymooners. The rap on Amos ‘n’ Andy has been that it perpetuates stereotypes of black men as lazy, shiftless, and dumb, and of black women as shrewish and unattractive. As for the men, those characterizations apply to only four characters in the series: Andy Brown (Spencer Williams Jr.), George “Kingfish Stevens (Tim Moore), Lightnin’ (Nick Stewart, billed as Nick O’Deamus), and the lawyer Algonquin J. Calhoun (Johnny Lee).

These men live in a universe in which virtually everyone is black and, significantly, in which everybody but them is dignified, moral, and responsible. Just as The Honeymooners didn’t imply that all white men were naive schemers like Ralph Kramden or good-natured dumbbells like Ed Norton, Amos ‘n’ Andy didn’t imply that all black men were lummoxes, wasters, or charlatans. In both cases, the point was that the main characters were out of step with everyone around them; they were the exceptions, not the rules.

The most prominent female character on Amos ‘n’ Andy was Sapphire Stevens, the Kingfish’s wife. Sapphire was played by Ernestine Wade, who actually was a pretty woman. Sapphire longed for a more genteel life in which she wasn’t hounded by bill collectors and in which she could associate with folks a little more erudite and stimulating than Andy Brown. Wade portrayed her as a decent woman who was faithful to a husband who didn’t deserve it; if Sapphire nagged the Kingfish and at times lost her temper with him, no one could blame her any more than they could blame Alice Kramden from blowing up at Ralph.

Less sympathetic a character, perhaps, was Ramona Smith, Sapphire’s mother, who was presented as the classic bellicose battleship of a mother-in-law — an accessory the Kingfish had in common with Ralph Kramden.

The broadest of the regular characters were the shambling, drawling Lightnin’, and Calhoun, a loudmouth and a fake.

There was a shift in emphasis in the television series in which Amos, although a title character and often the voice that introduced the episode (“Hello, folks. This is Amos. . . .”), became a secondary figure, and the Kingfish became the focal point of almost every episode. In the TV series, Amos was a level-headed, intelligent, soft-spoken, man who owned his own taxicab and led a quiet life with his lovely wife, Ruby, and their two daughters. Amos was often the Jiminy Cricket to the Kingfish and Andy, giving them sound advice and sometimes directly getting them out of trouble.

An aspect of this show that is always overlooked is the quality of the cast it brought together. Many of the actors had long careers as entertainers, persisting through an era in which they were unappreciated, type cast, and often rudely treated.

Tim Moore, who played the chronically unemployed and finagling Kingfish, had a remarkable life as a vaudevillian, entertaining all over the world. He also appeared in several Broadway shows and in films. He was even fairly successful as a boxer. He was lured out of retirement to play the role in Amos ‘n’ Andy. His character’s sobriquet was actually his title as head of the lodge — the kingfish. When he wanted his pals to bail him out of some scrape, he often reminded them, “After all, we are all brothers in that great organization, the Mystic Knights of the Sea.”

Spencer Williams Jr., who played the sweet but gullible oaf Andy Brown, was an important figure in the history of American film. A World War I army veteran who worked in many aspects of the movie business, including as a sound technician, eventually became a writer, director, and producer of so-called “race movies,” films that were made specifically to be shown in segregated theaters. His film “Go Down Jesus,” which was made on a $5,000 budget and with nonprofessional actors, was one of the most successful “race films” of all time. Time magazine called it one of the “25 most important films on race.”

Alvin Childress, who played the sensible and gentle Amos Jones, held a bachelor’s degree in sociology. He began working as an actor with a Harlem theater company, and he worked on both the stage and on film. He appeared on Broadway as Noah in Philip Yordan’s play Anna Lucasta, which ran for 957 performances. Although he appeared in a couple movies and in episodes of Perry Mason, Sandford and Son, Good Times, and The Jeffersons, Childress, who felt he had been typed by casting directors as Amos Jones, had a hard time sustaining his career. His first marriage, which lasted for 23 years, was to a well known writer and actress, Alice (Herndon) Childress.

Nick Stewart, who played Lightnin’, was a dancer and comedian who appeared in night clubs, Broadway shows, films, and radio. Stewart was the voice of Br’er Bear in the 1946 Disney movie Song of the South. In 1950, He and his wife, Edna, founded the Ebony Showcase Theater in Los Angeles, where for many years they provided a venue in which black actors could appear in quality productions.

Johnny Lee, who played the blustering, incompetent lawyer, Algonquin J. Calhoun, was a dancer and actor who appeared in a couple of dozen films and television shows, perhaps most notably as the voice of Br’er Rabbit in Song of the South. He had featured roles in Come On, Cowboy! (1948) and She’s Too Mean for Me (1948) and he played a stuttering bill collector in Boarding House Blues (1948). He also starred in an all-black musical comedy, Sugar Hill, at the Las Palmas Theatre in Hollywood in 1949. His last TV role was Mr. Gibbons the Locksmith on Dennis the Menace in 1963.

In addition to these regular players, Amos ‘n Andy provided occasional roles for some very talented actors, including the sisters Amanda and Lillian Randolph. Amanda Randolph, who played Ramona Smith, mother of Sapphire Stevens, was the first black actress to appear on a regularly-scheduled network television show. That was The Laytons, which appeared on the old Dumont network for two months in 1948. She was an exceptional jazz pianist and a composer. She appeared in New York musicals, entertained in Europe, performed in vaudeville, and cut records as both a musician and a vocalist. She appeared on Broadway, in films, and on radio. On radio, she played the title role in Beulah in the 1953-1954 season, inheriting the role from Lillian.

She was the first black American actress to have her own daytime network TV show — Amanda, which ran on Dumont in the 1948-49 season. Among her many TV roles was Louise, the wisecracking maid on Danny Thomas’s comedy series.

Lillian Randolph, who appeared in Amos ‘n’ Andy as Madame Queen, a former girlfriend of Andy Brown, was also a multi-talented performer on radio, television, and film. She had played Madame Queen on the radio, too, and made the character’s name a household word in the United States. She played the maid Birdie Lee Coggins in The Great Gildersleeve radio series, and she repeated the role in Gildersleeve films and the later TV series. Her performance of a gospel song on the TV series led to a gospel album on Dootone Records. She also made regular appearances on The Baby Snooks Show and The Billie Burke Show on radio. Her best known film roles probably were Annie in It’s a Wonderful Life and Bessie in The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer. Her television roles included Bill Cosby’s mother on The Bill Cosby Show, and Red Foxx’s aunt Esther on Sandford and Son. Altogether, she appeared in about 93 movie and television properties. In 1954, Lillian Randolph became the first black member of the board of directors of the Hollywood Chapter of the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.

One of the most eminent persons to appear on the Amos ‘n’ Andy TV series was Jester Hairston, who made occasional appearances as both Sapphire’s brother Leroy and as wealthy and dapper lodge member Henry Van Porter. Although he appeared in about 20 films and several TV shows, acting was secondary to Hairston’s career as a composer, songwriter, arranger, and choral conductor. He wrote the song “Amen” for the 1963 film Lilies of the Field and he dubbed the song for Sidney Poitier to lip-sync. He also wrote the Christmas carol Mary’s Little Boy Child. Harry Belafonte’s recording of the song reached No. 1 on the charts in the UK in 1957. From 1986 to 1991, Hairston played Rolly Forbes in the TV series Amen.

Hairston was a graduate of Tufts University, and he studied music at the Julliard School. He was highly regarded as a conductor of choirs, including on Broadway, and as a composer and arranger of choral music. In 1985, when few foreign performers were appearing in China, he took a multi-racial choir to tour the country. Hairston was a founder of the Screen Actors Guild.

Also among the actors who appeared on Amos ‘n’ Andy was Roy Glenn, who had a rich baritone-bass voice that he got to use in one episode, singing some lines from “Red Sails in the Sunset.” Glenn had a long acting career, appearing in 96 films and television shows. His most prominent role probably was Sidney Poitier’s father in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967).

The only Amos ‘n’ Andy alumnus I’m aware of who not only is still living but has worked as an actor recently is Jay Brooks, who appeared in two episodes of Seinfeld, as Sid, the man who provides a service in Jerry Seinfeld’s neighborhood by moving cars from one side of the street to the other to comply with New York City’s alternate-side parking regulations.

The actors who appeared on Amos ‘n’ Andy were often criticized for accepting roles on a show that some people felt was demeaning to black people. More often than not, the roles offered to black performers in those days in any venue were stereotyped if they weren’t out-and-out offensive. Some of the actors — Alvin Childress, for example — argued that they had to work where they could and that by accepting parts on the first all-black show on television, they had paved the way for others to follow. It’s too late to resolve that question but, taken on its own merits, Amos ‘n’ Andy was a funny show, due in large part to the performances of a lot of experienced actors who, over their careers, made enormous contributions to American popular culture. They don’t deserve to be forgotten.

Books: “A Natural Woman”

April 27, 2012

It may not be possible to dislike Carole King.

It may not be possible to dislike Carole King.

What’s not to like? She has written some of the best pop and rock songs of the past five decades, she has a record of social responsibility, and she’s a nice person.

In a way, her memoir, A Natural Woman, is similar: What’s not to like? It’s a conversational account of a remarkable American life; in some ways, it would be hard to believe if one didn’t already know that it’s true. King (Carol Klein) is a Brooklyn native who found herself in awkward straits in school because her mother enrolled her early, and then she skipped a grade — so she was perennially younger than her classmates and felt out of place.

She showed early signs of a bent for entertaining, and she was writing songs in her teens. In fact, she was only 18 when she and her husband, Gerry Goffin, wrote “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” for the Shirelles. She also became a mother for the first of four times at around the same time. Among the songs she has written since then, either on her own or with a collaborator, are “Where You Lead, I Will follow”; “I’m Into Something Good”; “It’s Too Late, Baby”; “The Loco-Motion”; “Take Good Care of My Baby”; “Go Away, Little Girl”; “I Feel the Earth Move;” “You’ve Got a Friend,” and “Natural Woman.’’

For a long time, King saw herself as a writer and “sideman” — that is, one of the musicians playing and even singing behind a lead performer. By King’s account, James Taylor changed that single-handedly. It occurred in 1970 while Taylor was touring to promote his album “Sweet Baby James.” King was to play piano for Taylor at a performance at Queens College, which was her alma mater. As the show was about to begin, Taylor told King he wanted her to sing lead that night on “Up on the Roof,” a song she had written with Goffin and a favorite of Taylor’s (and mine, not that it matters).

King writes that she was taken aback by this request but had no time to talk Taylor out of it. When that spot in the set came around, Taylor introduced King to the audience as an alumna of the college and a co-writer of the song and, without rehearsal, she took her first turn as a lead singer. In time, of course, she become a good enough lead that her album Tapestry become one of the best selling collections of all time.

King devotes a lot of space in this book to a personal life that is difficult for an outsider to fully understand. She married Goffin when she was 17, and the pair, barely more than children, settled into suburban life in West Orange. But Gerry got restless, he fooled around with drugs, he eventually plunged into serious depression. The marriage ended, but King and Goffin continued to be friends and collaborators. King had three more marriages, none of which, based on her own accounts, seem to have been well thought out. Two ended in divorce and one ended when her husband — who she says struck her on several occasions — died as a result of a drug overdose.

King emphasizes in this book that she didn’t like touring and that she didn’t seek stardom because of the baggage that came with it. She had a yen for a simple life, particularly as compared to life in the New York City and Los Angeles areas. From both a cultural and environmental point of view, she carried that quest to its logical extreme by buying a ranch in Idaho. Before she picked the spot, in fact, she and her fourth husband, Rick Sorensen, and her two youngest children lived for three years in a cabin that had no electricity, running water, or heat.

When King first decided to make Idaho her principal residence, her oldest child, Louise, then 17, declined to make the move, and she stayed behind in Los Angeles. Eventually, all of King’s children would wind up in California. All of those children apparently have had fruitful lives, but King’s priorities are still a little hard to grasp.

When King first decided to make Idaho her principal residence, her oldest child, Louise, then 17, declined to make the move, and she stayed behind in Los Angeles. Eventually, all of King’s children would wind up in California. All of those children apparently have had fruitful lives, but King’s priorities are still a little hard to grasp.

I found it disconcerting, too, that she devoted a chapter to her decision to practice yoga, remarking that the discipline helped her find her “center.” She presents this as a life-shaping event, but she never explains what she means by finding her center, and except for one glancing reference, she never mentions yoga again.

Perhaps because she is such a nice person, King chooses her words carefully when she’s describing her interactions with other people, even the husband who brutalized her. While it wouldn’t necessarily be useful for her to share any rancor she might be harboring, her approach is tentative enough to make a reader wonder what else she chose to withhold.

King mentions an editor in the acknowledgments, but I was happy to find that it seemed as if this book was largely King’s own work. It has the feel of a kitchen-table conversation. Apparently it is as much as King wanted to share, so it will have to do for now.

Once a year I have the terrifying privilege of preaching to children who are about to receive the Eucharist for the first time. It’s a May experience, and it took place again last Sunday morning. I am serious about both the noun – privilege – and the adjective. In fact, I told the children last Sunday that I approached them with trepidation, because I am accustomed to having a written homily lying in front of me there in the ambo, even if I seldom look at it. When I speak to the children, I have to do it standing in the center aisle, close to them, and speak informally. I’m not comfortable doing that.

Once a year I have the terrifying privilege of preaching to children who are about to receive the Eucharist for the first time. It’s a May experience, and it took place again last Sunday morning. I am serious about both the noun – privilege – and the adjective. In fact, I told the children last Sunday that I approached them with trepidation, because I am accustomed to having a written homily lying in front of me there in the ambo, even if I seldom look at it. When I speak to the children, I have to do it standing in the center aisle, close to them, and speak informally. I’m not comfortable doing that.

In order to have at least something to cling to, I always bring a prop on these occasions. I have brought my Howdy Doody dummy, my “first communion” picture, a set of juggling balls – anything to create a focal point other than me for the three or four minutes of this enterprise.

So last Sunday I brought Raggedy Ann and Andy, two large dolls that I bought for Pat about 35 years ago. They were hand-made by a woman who at the time was about 100 years old, and they are exquisite. Pat’s appreciation of their exquisite-ness has faded as the house has become increasingly burdened with more than 40 years of such acquisitions, and she has encouraged me to sell the dolls or give them away. Instead of doing that, I have taken possession of them, and I keep them in my clothes closet where I can see them every day.

So last Sunday I brought Raggedy Ann and Andy, two large dolls that I bought for Pat about 35 years ago. They were hand-made by a woman who at the time was about 100 years old, and they are exquisite. Pat’s appreciation of their exquisite-ness has faded as the house has become increasingly burdened with more than 40 years of such acquisitions, and she has encouraged me to sell the dolls or give them away. Instead of doing that, I have taken possession of them, and I keep them in my clothes closet where I can see them every day.

I used that image to build a homily about friends who never turn their backs on you. I began by producing the dolls out of a large gift bag and asking the children to identify these two stuffed characters. Most of the kids didn’t know. Only one girl was able to identify both dolls. My homily didn’t depend on the children knowing the names of the dolls, but I couldn’t help feeling a little twinge of melancholy as I saw the boys and girls look blankly at the once iconic figures.

Raggedy Ann was created in 1905 by a talented writer-cartoonist, Johnny Gruelle, when he drew a face on a rag doll for his daughter, Marcella, and derived the name from the titles of two poems by James Whitcomb Riley– The Raggedy Man and Little Orphant Annie. The term “orphant” was an example of the Hoosier dialect Riley adopted in his work. The second poem was the inspiration for the cartoon character Little Orphan Annie. WhenMarcella was 13, she contracted diphtheria after being vaccinated at school. She died shortly thereafter, and the Gruelles attributed her death on the medication she had received. Johnny Gruelle became a leading critic of vaccination, and Raggedy Annie was for a time the symbol of the movement.

In 1918, Gruelle – who was the son of American impressionist painter Richard Buckner Gruelle– published a children’s book, Raggedy Ann Stories, and a doll was sold in connection with it. The brother of the original character was introduced in 1920 in Raggedy Andy Stories. There were more than 40 subsequent books, some of them written and illustrated by Gruelle and some by others. The characters spawned a wide variety of other products, many of which are still on the market — even if the parents in my parish aren’t buying them.

I heard a report on National Public Radio last fall about the closing of the Liberace Museum in Las Vegas. The museum once drew 450,000 visitors a year — as many as stopped by Hoover Dam — but the outlandish pianist’s appeal had no staying power, and the people who did care grew old. Who thought that would happen to reliable old Raggedy Ann and Andy, but it has. Their museum, which was located in Gruelle’s home town of Arcola, Illinois — admittedly not on The Strip — closed its doors in 2008.

I heard a report on National Public Radio last fall about the closing of the Liberace Museum in Las Vegas. The museum once drew 450,000 visitors a year — as many as stopped by Hoover Dam — but the outlandish pianist’s appeal had no staying power, and the people who did care grew old. Who thought that would happen to reliable old Raggedy Ann and Andy, but it has. Their museum, which was located in Gruelle’s home town of Arcola, Illinois — admittedly not on The Strip — closed its doors in 2008.

Where have you gone, Carmen Miranda?

April 21, 2011

The allusion to Carmen Miranda on this week’s episode of “Modern Family” got us to thinking about her for the first time in recent memory. Our first reaction was to wonder how many people in, say, their 40s or less who were watching that show would have known who Carmen Miranda was. When she was in her heyday, there was no need to ask; she was very popular — with good reason — and she was very successful.

The allusion to Carmen Miranda on this week’s episode of “Modern Family” got us to thinking about her for the first time in recent memory. Our first reaction was to wonder how many people in, say, their 40s or less who were watching that show would have known who Carmen Miranda was. When she was in her heyday, there was no need to ask; she was very popular — with good reason — and she was very successful. Carmen Miranda was born in Portugal in 1909, but she grew up in Brazil. She began performing at an early age, although financial stresses on her family led her to a short-lived but profitable career as a milliner. She continued to pursue her musical career, though, and before she came to the United States in 1939, she was already established as a star on radio, recordings, and film. She ultimately made 14 Hollywood movies and at one point was the highest-paid woman in the industry. She also made occasional appearances in the variety-show format that was a staple in early American television.

Carmen Miranda was born in Portugal in 1909, but she grew up in Brazil. She began performing at an early age, although financial stresses on her family led her to a short-lived but profitable career as a milliner. She continued to pursue her musical career, though, and before she came to the United States in 1939, she was already established as a star on radio, recordings, and film. She ultimately made 14 Hollywood movies and at one point was the highest-paid woman in the industry. She also made occasional appearances in the variety-show format that was a staple in early American television. Carmen Miranda was subject to some criticism in Brazil during her lifetime on the grounds that she had become too Americanized and was presenting an inaccurate image of Brazilian culture. She was so upset by this evaluation of her work that she stayed away from Brazil for many years. Now, however, she is memorialized by museums in both Brazil and Portugal. She is also the namesake of Carmen Miranda Square at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Orange Drive, across from Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

Carmen Miranda was subject to some criticism in Brazil during her lifetime on the grounds that she had become too Americanized and was presenting an inaccurate image of Brazilian culture. She was so upset by this evaluation of her work that she stayed away from Brazil for many years. Now, however, she is memorialized by museums in both Brazil and Portugal. She is also the namesake of Carmen Miranda Square at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Orange Drive, across from Grauman’s Chinese Theater.“They can go to hell” — Mohamad al-Fayed

April 11, 2011

In the Capitoline Museum in Rome there is a bronze statue of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. This is the only complete bronze statue of a Roman emperor that still exists. It was erected while the old stoic was in office – 176 AD. The reason that there are no other bronze statues from that era is that it was routine in the fourth and fifth centuries to melt them down so that the metal could be used for other statues or for coins. Sic semper gloria, as the saying goes. Statues of the emperors were destroyed also because Christians — apparently with no regard for the historical curiosity of future generations — regarded them as offensive remnants of paganism. In fact, it is said that the statue of Marcus Aurelius survived because it was erroneously thought to be an effigy of the sort-of Christian emperor Constantine.

It has not been unusual for statues of great, or at least dominant, figures to be desecrated by unappreciative come-latelies. Just the other day, some Syrians who are impatient with the fact that they lack basic political and economic rights did insulting things to an image of their former president, Hafez al-Assad, affectionately known as the “butcher of Hama” because of an unpleasant incident in which he caused the deaths of from 17,000 to 40,000 people.

There was some unpleasantness of a different sort about 8 years ago concerning a statue erected in Richmond representing Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad. The statue reflects on Lincoln’s visit to the ruined city in April 1865 at the end of the Civil War. There were bitter protests by people who objected to the statue, apparently still not able to concede Lincoln’s conciliatory attitude toward the southerners whose treason brought on the war in the first place.

Meanwhile, there has been some statuary-related turmoil in England. The trouble isn’t about figures of Neville Chamberlain or Guy Fawkes or Edward VIII. No, the man at the center of the maelstrom is Michael Jackson. There are two new statues of Jackson in place in the UK, and both of them are getting the raspberry from some of Jackson’s fans.

One scuffle is about a statue of Jackson dangling his baby son out of a hotel window. The life-sized image — which the artist calls “Madonna and Child” — recalls the incident in which Jackson held his son Prince Michael II out of a window in Berlin in 2002 while hundreds of fans were gathered below.

The sculpture is by a Swedish-born artist named Maria von Kohler; it’s displayed in the window of a music studio in East London. Jackson’s fans — who apparently haven’t been lured away by any of Simon Cowles’ instant sensations — find the sculpture revolting. They see it as an part of a persistent campaign of slander against Jackson, who set the bar for slander rather high. Viv Broughton, chief executive of the music studio, has a different view. He called the sculpture a “thought-provoking statement about fame and fan worship.”

The other skirmish has been prompted by a statue of Jackson erected outside Craven Cottage Stadium in London. The stadium is the home of the Fulham Football Club, a soccer team. Mohamed al-Fayed — whose son Dodi died in the auto accident that killed Princess Diana — owns the football club. The elder Fayed was a friend of Jackson.

Art critics have had a field day with the statue and some of Jackson’s disciples have criticized it, too.

Fayed responded to the criticism with a certain delicacy: “If some stupid fans don’t understand and appreciate such a gift, they can go to hell.”

I’ve often thought, when I pass the statue of Vice President Garret Hobart in front of City Hall in Paterson, how melancholy he must be as hundreds of people pass him each day without a glimmer of recognition. On the other hand, he has nobody attacking him except the pigeons.

The worst of the year?

September 11, 2010

I always read those warnings that accompany films — the ones designed to steer you, or prompt you to steer your children, away from what you consider offensive. The Joaquin Phoenix film “I’m Still Here” may not be unique in this regard, but it is for me — the first film I have seen in which the content warnings include “defecation.”

I always read those warnings that accompany films — the ones designed to steer you, or prompt you to steer your children, away from what you consider offensive. The Joaquin Phoenix film “I’m Still Here” may not be unique in this regard, but it is for me — the first film I have seen in which the content warnings include “defecation.”

I generally don’t care about foul language, and nudity and sexuality aren’t show stoppers for me if they’re important to the context of the film, but defecation? Check, please!

I wouldn’t have seen this film even without the crap, as it were, because I’m not sufficiently interested in Joaquin Phoenix whether he’s drawing Oscar nominations or coming apart at the seams. What I do find amusing, though, is the coverage of this film — and particularly the speculation about whether it’s a true documentary, as billed, or whether it’s a put-on or a little of each.

I wouldn’t have seen this film even without the crap, as it were, because I’m not sufficiently interested in Joaquin Phoenix whether he’s drawing Oscar nominations or coming apart at the seams. What I do find amusing, though, is the coverage of this film — and particularly the speculation about whether it’s a true documentary, as billed, or whether it’s a put-on or a little of each.

Critics don’t often find themselves having to wonder aloud whether they’re watching fact or fiction, but they do in this case. Sheila Marikar of ABC News, for example, writes: “Joaquin Phoenix could be the most narcissistic, sniveling, drugged-up mess of a man ever to appear on a screen. Or he could be the greatest actor of all time. After watching ‘I’m Still Here,’ the just-released documentary that chronicles his 2008 departure from Hollywood and attempt to launch a rap career, the former seems more believable.”

Steven Rea in the Philadelphia Inquirer writes: “Joaquin Phoenix is either one of the greatest actors ever to walk the red carpet on his way to that Entertainment Tonight sound bite, or he’s an insufferably neurotic, narcissistic, doped-up jerk.

Steven Rea in the Philadelphia Inquirer writes: “Joaquin Phoenix is either one of the greatest actors ever to walk the red carpet on his way to that Entertainment Tonight sound bite, or he’s an insufferably neurotic, narcissistic, doped-up jerk.

“Whichever turns out to be the case (I’m betting on the latter), ‘I’m Still Here’ — the documentary-like chronicle of a year in the life of the twice-Oscar-nominated thespian, as he announces his retirement from movies to pursue a career as a hip-hop artist – stands as a fascinating look at the cloistered, coddled world of a movie star who’s not quite up there in the A-list tier of, say, Leo or Tobey.”

“And Manohla Dargis of the New York Times describes the film as “a deadpan satire or a deeply sincere folly (my money is on the first option) about Mr. Phoenix’s recent roles as an acting dropout and would-be hip-hop artist.”

I don’t want to go into detail about the contents of this film — the verbal abuse, the coke snorting, the prostitution, the revolting manners and, indeed the defecation — but it is spelled out in Laremy Legel’s review in the Seattle Post-Dispatch.

In 1958, a critic discussing the Broadway play “Make a Million” said he had spent the previous evening “laughing at a very bad play.” Legel acknowledges that he laughed at some parts of this film, which was directed by Casey Affleck, who is married to Phoenix’s sister.

Legel gets to the heart of the matter when he addresses the pretense that this is a documentary account of a man who has rejected both the work and the milieu of Hollywood and set out to build himself a new career:

“We don’t see him working on his craft, we don’t see him in the clubs trying to get better, we don’t see him reaching out to rappers or starting a writing notebook. What we do see is his him leveraging his celebrity to cause a spectacle. What we do see is him not taking it seriously. What we do see is him not caring, which would be fine, if only he didn’t ask us to instead.”

From what I can discern, Phoenix is a jerk and this movie is garbage, and yet Phoenix also seems to have gotten what he was probably after all along. Everyone is writing about him — including me.

“Ungo empee stur. Wonting?”

August 3, 2010

A couple of years ago, I stumbled across an anonymous post on a blog in which the writer was talking about — of all people — me. The writer was musing over the fact that I had been laid off from my newspaper after 43 years. That’s neither here nor there, but I was interested in his description of me as a “raspy-voiced guy with a North Jersey accent.” I was not aware that I had an accent — North Jersey or otherwise. In fact, I’m not sure there is such a thing as one North Jersey accent, and I don’t hail from the Hudson River towns that are usually associated with “joisey” talk.

A couple of years ago, I stumbled across an anonymous post on a blog in which the writer was talking about — of all people — me. The writer was musing over the fact that I had been laid off from my newspaper after 43 years. That’s neither here nor there, but I was interested in his description of me as a “raspy-voiced guy with a North Jersey accent.” I was not aware that I had an accent — North Jersey or otherwise. In fact, I’m not sure there is such a thing as one North Jersey accent, and I don’t hail from the Hudson River towns that are usually associated with “joisey” talk.

This came to mind yesterday when I was listening to a presentation on WNYC radio about the accents in New York. There was a segment on the Brian Lehrer Show — absent Brian Lehrer who, I suppose, was on vacation — featuring Heather Quinlan, a TV producer who is producing a documentary called “If These Knishes Could Talk” and Sam Chwat, a speech therapist or pathologist who, among other things, helps actors who need to alter their speech for specific roles.

For my money, this discussion didn’t live up to its promise. Perhaps one of the reasons was that — as one listener commented on the show’s web site — neither of the guests is a linguist. I was disappointed, because this subject has always interested me, and I listen very carefully to how people speak. I like National Public Radio, in fact, not only because of all the information it provides but because of the many accents. I like listening to the accents of speakers whose first language was something other than English, but I have a special fascination with the many ways in which native speakers use English.

There are two aspects of speech variations: pronunciations and choice of words. Word choice , I understand, can vary not only from one region of the country to another but within a single state. For example, the pasta known as penne is known in the Chambersburg section of Trenton, here in New Jersey, as “pencil points.” And I read a magazine article many years ago in which the writer claimed to demonstrate that submarine sandwiches are called by different names — subs, hoagies, grinders, or heroes — in different sections of this state.

I’m more interested in pronunciation. When I lived for a year at Penn State in central Pennsylvania, it was a regular smörgåsbord of accents, because the tens of thousands of students and hundreds of faculty came from all over the world to mix in with folks who lived in what was then an otherwise isolated area. My immediate neighbors were from Iran and North Carolina.

I’m more interested in pronunciation. When I lived for a year at Penn State in central Pennsylvania, it was a regular smörgåsbord of accents, because the tens of thousands of students and hundreds of faculty came from all over the world to mix in with folks who lived in what was then an otherwise isolated area. My immediate neighbors were from Iran and North Carolina.

There’s no beating New York City, though, for feasting your ears on varieties of speech. One of my favorite moments in that respect occurred in an Italian bakery in lower Manhattan. While a friend and I were talking to the woman behind the counter, a man — evidently her husband — came from a back room and headed for the front door while pulling on his jacket. “Ungo empee stur,” he said to her over his shoulder. “Wonting?” (“I’m going to the A&P store. Want anything?”)

PBS has a fun exercise on its web site in which you can listen to various voices and try to place them by region on a map of the United States. To see it, click HERE.

“Why are we here? Where are we going?” — Lew Brown

August 1, 2010

Sometimes we meet people in unexpected ways. For example, I met Lew Brown, who died 52 years ago, while I was struggling to write a sermon yesterday. We homilists are supposed to base our message on the readings of the day, and today’s readings have a consistent theme: Don’t neglect your spiritual well-being while you’re absorbed in accumulating possessions and other forms of material wealth. The first reading is from the Book of Ecclesiastes (“For what profit comes to a man from all the toil and anxiety of heart with which he has labored under the sun?”); St. Paul’s letter to the Christian community in Colossae (“Think of what is above, not of what is on earth”); and the Gospel according to Luke (“Though one may be rich, one’s life does not consist of possessions”).

Sometimes we meet people in unexpected ways. For example, I met Lew Brown, who died 52 years ago, while I was struggling to write a sermon yesterday. We homilists are supposed to base our message on the readings of the day, and today’s readings have a consistent theme: Don’t neglect your spiritual well-being while you’re absorbed in accumulating possessions and other forms of material wealth. The first reading is from the Book of Ecclesiastes (“For what profit comes to a man from all the toil and anxiety of heart with which he has labored under the sun?”); St. Paul’s letter to the Christian community in Colossae (“Think of what is above, not of what is on earth”); and the Gospel according to Luke (“Though one may be rich, one’s life does not consist of possessions”).

It’s a message we hear often. In other words: Been there, done that.

And so I thrashed around for several hours, trying to find a way into this homily. I looked back at hooks I had used the last few times these readings came up in the three-year cycle, but they seemed contrived and heavy-handed — as my writing often seems to me after some time has passed. Then, as we like to say in the church, the Holy Spirit put a song in my head: “Life is just a bowl of cherries / Don’t take it serious / Life’s too delirious / You live, you love, you worry so / but you can’t take your dough / when you go, go, go.”

And so I thrashed around for several hours, trying to find a way into this homily. I looked back at hooks I had used the last few times these readings came up in the three-year cycle, but they seemed contrived and heavy-handed — as my writing often seems to me after some time has passed. Then, as we like to say in the church, the Holy Spirit put a song in my head: “Life is just a bowl of cherries / Don’t take it serious / Life’s too delirious / You live, you love, you worry so / but you can’t take your dough / when you go, go, go.”

The lyric was a pop iteration of the central theme of today’s readings and, because the tune is still familiar, I decided to use it. When I set out to find out who wrote the lyrics, I found several web sites that attributed it to George Gershwin who, of course, was not a lyricist. I also found it attributed to Ira Gershwin, who was. That didn’t sound right to me, so I persisted, and I found out that the lyric was written by Lew Brown for the Broadway review “George White’s Scandals of 1931.” (Pay attention, boys and girls. You can’t trust internet sources.)

When the song is performed now, it usually seems to recommend a carefree life, but Brown wrote it at the onset of the Great Depression when it had a different connotation. As is frequently the case with popular lyrics, these at least touch on pretty serious ideas: “The sweet things in life / to you are just loaned / so how can you lose / what you’ve never owned?”

Like Irving Berlin, Lew Brown was born in the latter 19th century in tsarist Russia, and like Berlin, his family brought him to New York City when he was child. Brown began writing songs when he was still attending Dewitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and by 1912, when he was 19 years old, he had his first hit, “I’m the Lonesomest Gal in Town,” and he had another in 1916, “If You Were the Only Girl in the World (and I Was the Only Boy)”. The scores for both were written by Albert von Tilzner, with whom Brown collaborated on several other tunes. “If You Were the Only Girl in the World” became an American standard, and it would be only one of many for which Brown — either solo or as a collaborator — provided the words. He teamed up for a long time with composer Ray Henderson, and together they wrote the song that prompted this blog and one of my favorites, “The Thrill is Gone,” which was also written for the “George White Scandals.” Other songs he had a hand in were “The Beer Barrel Polka,” “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (With Anyone Else but Me),” “Sonny Boy,” “It All Depends on You,” “The Best Things in Life Are Free,” and “You’re the Cream in My Coffee.”

Lew Brown — who was born Louis Brownstein — died in 1958, never expecting to help a tin-horn deacon preach the gospel. Thanks, Lew . . . for everything.