“Of castles on the Rhine, candlelight and wine . . .”

September 27, 2013

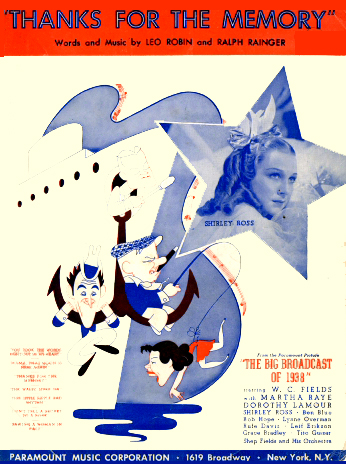

Jack Benny occasionally played his theme song on the violin, but to my knowledge, he never sang it on the air, if at all. That makes Benny and “Love in Bloom,” the topics of my last post, unusual among performers and their signature songs. Perhaps the best example of the more typical approach is Bob Hope and “Thanks for the Memory.”

Hope’s theme, as it happens, was written by the same artists who wrote “Love in Bloom.” Ralph Rainger composed the music, and Leo Robin provided the lyrics.

Rainger and Robin wrote the song for The Big Broadcast of 1938, the last in a series of such musical films from Paramount. This plot for this one involved a trans-Atlantic race by two ocean liners. The ensemble included W.C. Fields, Hope and Ross, Martha Raye, Dorothy Lamour, Ben Blue, and Kirsten Flagstad.

Ross and Hope play a couple who are near the point of divorce. In “Thanks for the Memory,” they reminisce about the high and low points of their relationship — a relationship, incidentally, which survives after all. The song won an Academy Award.

Ross and Hope got to team up the following year and sing another song that became an American classic: “Two Sleepy People” by Frank Loesser and Hoagy Carmichael. That duet was in a film titled “Thanks for the Memory.”

Hope adopted “Thanks for the Memory” as his theme, and sang it at the end of his live and televised performances for the rest of his career, changing the lyrics to fit the situation. It was an interesting choice for a comedian, because its original meaning was melancholy, and even when Hope’s writers put humorous lines in it, the sad undercurrent was always there. That was particularly true when Hope sang “Thanks for the Memory” at the end of the many shows he performed for American troops.

Ralph Rainger wrote scores for at least 40 movies. He would have written for many more, but he was killed in an air collision in 1942 when he was only 41 years old. The DC-3 he was traveling on collided with a U.S. Army Air Corps bomber over Palm Springs.

You can see and hear Bob Hope and Shirley Ross singing “Thanks for the Memory” in The Big Broadcast of 1938″ by clicking HERE.

“Oh, no, it isn’t the trees . . . .”

September 23, 2013

I was about to watch an episode of the Jack Benny Program recently when I became absorbed in the opening theme. The theme is associated not just with the television series but with Jack Benny himself. The song, “Love in Bloom,” was not written by amateurs. The music was by Ralph Rainger and the lyrics by Leo Robin. Ralph Rainger, a member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame, wrote a lot of music for movies between 1930 and 1942. One of his compositions, “Thanks for the Memory,” written for The Big Broadcast of 1938, won an Academy Award. (I’ll have more to say about that song in a later post.) Leo Robin, who wrote the lyrics to “Love in Bloom,” is also a member of the Hall of Fame. His work included “Thanks for the Memory,” “Beyond the Blue Horizon,” “Prisoner of Love,” and “Blue Hawaii.”

“Love in Bloom” was introduced in 1934 in the film She Loves Me Not. It was sung in a duet by Bing Crosby and Kitty Carlisle.

Crosby, that same year, was the first to record the song, which was nominated for an Academy Award.

Kitty Carlisle — an elegant woman whom, incidentally, I once visited at her Manhattan apartment — liked the song enough that she considered adopting it as her own theme. She scuttled that idea, however, when Benny made the song his signature, frequently playing it, and deliberately butchering it, on his violin.

The song has qualities that don’t come across in most of Benny’s renditions. You can see for yourself as Crosby and Kitty Carlisle sing it in the film. Click HERE.

You can also see a hiliarious routine in which Benny and Liberace play the song on the keyboard and violin on a 1969 episode of Liberace’s TV show. Here Benny lets himself show, for a while at least, that he was more competent on the violin than he cared to admit. Click HERE.

A man named “Birmingham”

August 30, 2013

My recent post about Eddie “Rochester” Anderson got me to thinking about another black actor of that generation — Mantan Moreland, who sometimes used the name “Birmingham” Brown. Moreland was born in Louisiana in 1902 and as a child repeatedly left home to look for work in circuses and other road shows. He eventually got into vaudeville, working the tanktown circuit, but also appearing on Broadway and touring Europe.

Like many actors with similar resumes, Moreland developed a lot of skills while he was doing that work, and he eventually put them to use on the screen, appearing in at least 130 movies and television shows, but mostly movies. He worked in so-called race movies (movies made by black producers for black audiences), in shoestring productions, and in major features, and he created his most indelible impression in the role of “Birmingham” Brown, chauffeur to the film detective, Charlie Chan, who ostensibly was Chinese, though he was played by Caucasian actors. The character of “Birmingham” Brown, like most of the characters Moreland played, perpetuated stereotypes about black people. Specifically, the bug-eyed Birmingham was afraid of everything and often tried to dissuade Chan from wading into dangerous situations. His entreaty — “Mistuh Chan! Mistuh Chan!” — became familiar to millions of moviegoers in the 1940s and to a later generation of television viewers when the Charlie Chan films resurfaced on the small screen. Of course, the portrayal of Chan himself was problematic in its own way.

Monogram Studios, which made the 15 Charlie Chan films in which Moreland appeared, thought enough of his comic abilities to give him second billing.

The major properties Moreland appeared in included A Haunting We will Go, with Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy; Cabin in the Sky, and See Here, Private Hargrove.

White filmmakers and white audiences were content for decades to take advantage of the willingness of black actors to play subservient or demeaning roles, but when the nation became uncomfortable with, or at least self-conscious about, that kind of comedy, many black performers had a hard time getting any work at all.

Mantan Moreland himself, along with many of his black peers, was conflicted about the image they presented while they were trying to establish themselves as entertainers and, not incidentally, make a living. Moreland, in hindsight, judged the epoch harshly, telling an interviewer in 1959 that he would “never play another stereotype, regardless of what Hollywood offers.”

“The Negro, as a race,” Morehead said, “has come too far in the last few years for me to dash his hopes, dreams, and accomplishments against a celluloid wall, by making pictures that show him to be a slow-thinking, stupid dolt. … Millions of people may have thought that my acting was comical, but I know now that it wasn’t always so funny to my own people.” After that, he did appear in a few movies and in television series including Adam-12, The Bill Cosby Show, and Love American Style.

When Moreland was touring in vaudeville, he often worked with a comic named Ben Carter, and the two developed a routine known as “incomplete sentence” in which they carried on a rapid conversation in which neither could finish a sentence. It required a firm command of the material and impeccable timing. Moreland and Carter brought the routine to the movie screen by way of the Charlie Chan films. You can see clips of the routine if you click HERE.

Netflix Update No. 79: “Marvin’s Room”

July 30, 2013

If blood is, indeed, thicker than water, does the same chemistry apply to bone marrow? That question is at the heart of the matter in “Marvin’s Room,” a 1996 film produced by Robert De Niro and starring Diane Keaton, Meryl Streep, Leonardo Di Caprio, Gwen Verdon, and Hume Cronyn.

The story, which is based on a play by Scott McPherson, concerns the uneasy reunion of a badly fractured family. The Marvin of the title (Cronyn) has been bed-ridden at his Florida home for 17 years after suffering a stroke. Unable to walk or to speak coherently, Marvin is cared for by his daughter Bessie (Keaton), who also looks after her aunt Ruth (Verdon), who is in the early stages of dementia.

Bessie is diagnosed with leukemia and needs a marrow transplant. She turns for help to her sister Lee (Streep) although they haven’t communicated since Lee moved to Ohio 20 years ago. Lee has two sons who are potential donors, Hank (DiCaprio) and Charlie (Hal Scardino). Lee and Hank have a poisonous relationship which recently reached new depths when he was confined to a mental health facility after deliberately setting fire to their house.

Despite the mutual hard feelings between the sisters, Lee takes her sons to Florida to be tested for compatibility, although Hank is coy about whether he would agree to donate marrow even if he were a match. The atmosphere is uncomfortable and not made any better when Lee considers the possibility that she could inherit this responsibility if Bessie should die.

There is an unexpected chemistry between Bessie and Hank, however, and the story turns on that, though not in a simplistic way.

This film was very well received when it first appeared, and with good reason. Although the premise has all the potential for a sob story, it is written and directed (by Jerry Zaks) into a tense and moving drama. The unusual array of stars (which includes De Niro as Bessie’s doctor) delivers on its promise, too.

Netflix Update No. 78: “The Magic of Belle Isle”

April 14, 2013

Sometimes it’s better to accept the plot of a movie and move on. The Magic of Belle Isle is a case in point.

This feel-good film, released in 2012, was written by Guy Thomas and directed by Rob Reiner. The story concerns Monte Wildhorn (Morgan Freeman), who was once a successful author of novels about a cowboy named Jubal McLaws. Disappointments in his life have dried up his creativity, and he is spending a summer at a borrowed house in fictional Belle Isle (actually Greenwood Lake, N.Y.), where he plans to drink and be disagreeable.

Partly due to his Victorian manners, he grudgingly develops relationships with people in the neighborhood, including Charlotte O’Neil (Virginia Madsen) the attractive divorcee next door, and her three daughters.

Monte especially becomes engaged with Charlotte’s middle daughter, Finnegan (Emma Fuhrmann), for whom the concept of imagination is elusive. There is also an undisguised chemistry between Monte and Charlotte — an improbable couple by reason of their widely different ages.

In a side plot not wholly irrelevant to the main story, the O’Neil children are going through the pain of separation from their father — an issue that creates a great deal of tension between Charlotte and her oldest girl, Willow (Madeline Carroll).

There is also a sidebar concerning Monte’s positive influence on a mentally or emotionally challenged young man (Ash Christian) who likes to hop around town like a bunny.

If one wonders too hard about how Monte, who has no use of his left arm and leg, can manage to do all the things that go along with living alone, or how he can drink as much as he does and sober up enough to be a good neighbor … well, if wonders too hard about a lot of things in this story, one may miss the benefits of good acting by a talented cast, a visually pleasing presentation, and a little optimism about human nature.

Neflix Update No. 77: “Jellyfish”

March 19, 2013

Sometimes a mesmerizing movie is one that leaves you uncertain as to what you just saw. Jellyfish (Meduzot in Hebrew) — a 2007 Israeli film, fits that category.

This dramatic comedy, or is it comic drama — see what I mean? — is based on a story by Shira Geffen. The subject matter is the frustrating lives of three women living in Tel Aviv. On the one hand, they are all lonely and downbeat — “resigned” might be the best term — but at the same time there is a spark of humor and warmth in the connections among them.

Batya, played by Sarah Adler, works somewhat ineptly in a dead-end job at a banquet hall. She is fired by her boorish boss, thrown over by her boyfriend, and neglected by her high-profile mother. Not unexpectedly, Batya isn’t in a good mood most of time, but her life is charmed when she encounters a mysterious mute little girl (Nikol Leidman) who wades out of the sea with a flotation tube around her waist and no other visible means of support, notably parents.

Things don’t go much better for Keren, played by Noa Knoller, a newly married bride whose Caribbean honeymoon is derailed before it starts when she breaks her leg while trying to climb out of a locked bathroom stall. And Joy (Ma-nenita De LaTorre), an immigrant who cares for a disagreeable old woman, is lonely for the son she left behind in the Philippines.

Clearly, a strain of melancholy runs through this film, but in the end it is not a downer. While it portrays the weightiness of everyday urban life, it also explores the undramatic but positive things that can touch people when their lives intersect.

Neflix Update No. 76: “The Long Walk Home”

February 22, 2013

I am in the process of reviewing a new book about the Emacipation Proclamation.

I am in the process of reviewing a new book about the Emacipation Proclamation.

The book is heavily illustrated, and some of the pictures are photographs of people who were held in slavery in this country. I often pause over pictures like that, studying the faces. The faces remind me of the painful fact that epochs such as American slavery, Jim Crow, and the Holocaust were about the injustice and pain inflicted on individual men, women, and children.

The 1990 film The Long Walk Home makes that point with a sharp impact. The story, originally written by John Cork when he was a student at the University of Southern California, is set in Montgomery, Alabama, during the bus boycott of 1955-1956. That was the seminal protest against racial discrimination on the city’s transit system, sparked by the arrest of Rosa Parks for refusing to surrender her seat to a white man. The stand taken by Rosa Parks inspired a boycott of the bus system by black citizens of Montgomery and eventually led to a ruling by the U.S. Supreme court that the racially discriminatory laws in Montgomery were unconstitutional and must be vacated.

The cast of The Long Walk Home includes Whoopie Goldberg as Odessa Carter, a maid employed by Miriam Thompson, played by Sissy Spacek.

Miriam Thompson is affected by the boycott, because Odessa won’t ride the bus, and the long walk, besides being grueling, makes her late for work each morning. Miriam’s partial solution to that is to pick up Odessa two mornings a week, a decision that Miriam’s husband, Norman (Dwight Schultz), goaded by his redneck brother, Tunker (Dylan Baker), vehemently objects to. The growing tension in the Thompson family over this issue, and her observation of Odessa’s ordeal, lead Miriam to re-examine her own values and her place in the roiling civil rights issue in the city.

This is a good movie in many respects, including Whoopi Goldberg’s understated performance as a woman who solemnly decides that she has had enough of being patronized, de-humanized, and humiliated. It’s important that she is portrayed in the midst of her own family, her husband and children. Shifting the point of view to this setting reminds us that racial discrimination didn’t do violence to some abstract principle; it did violence to regular people who were trying to live as human beings and citizens.

Netflix Update No. 75: “From Time to Time”

December 27, 2012

I have written in this space about several movies that had time-travel themes, but none so elegant as From Time to Time, a 2009 British production directed by Julian Fellowes.

The story is set in a country estate in England at the end of World War II. A 13-year-old boy named Tolly, played by Alex Etel, is sent to stay at the old house with his grandmother, Mrs. Oldknow, played by Maggie Smith. Mrs. Oldknow’s son — who is Tolly’s father — has been missing in action, and Tolly is holding onto a conviction that his dad is still alive. Tolly’s mother, who has had a cool relationship with Mrs. Oldknow, is occupied with trying to determine her husband’s fate, and she believes Tolly would be safer in the country until the war is over.

Tolly is very interested in the house and in his ancestors who have lived there, and he is distressed to learn that his grandmother, who has a great affection for her home and loves to tell Tolly stories about its past, can no longer afford to keep the place up and is planning to sell it.

As Tolly explores the house and the grounds, he begins slipping from the mid-twentieth century into a time two hundred years before. He enters a room and finds it occupied by his ancestors and their retinue. Chief among these figures is the master of the house, a magnanimous sea captain played by Hugh Bonneville. Most of these shadows are unaware of Tolly, but one who is immediately sensible of his presence is Capt. Oldknow’s blind young daughter, Susan (Eliza Bennett). Susan is inadvertently the cause of a family crisis when Capt. Oldknow returns from one of his voyages with a black boy, a fugitive American slave named Jacob (Kwayedza Kureya). This lad, the captain announces, is to be a companion for Susan, and he is to be treated as a member of the household, not as a servant. This is met by resistance from Capt. Oldknow’s restless wife, Maria (Carice van Houten), his spoiled son Sefton (Douglas Booth), and from a none too disinterested servant named Caxton (Dominic West). The jealousy and antagonism directed at Jacob when the captain is away from home sets off a chain of events that results in a mystery that is not resolved until Tolly, the inquisitive time traveler, sorts it out.

This movie gets only fair to middlin’ reviews, but we found it entertaining and engaging. The quirky characters, including Pauline Collins as the latter-day household’s outspoken cook, Mrs. Tweedle, and Timothy Spall as the gruff Dickensian handyman whose bloodline has a critical place in the Oldknow family history.

Like a lot of people, I suspect, I have been fascinated by the idea of time travel since I was a kid and have fantasized about the day when I myself could visit the past. According to a physics book I read not long ago, time travel to the future is possible, but time travel to the past is out of the question. It’s not out of the question in the movies, though, so that’s where I do it, and it has never been more fun than in this film.

Netflix Update No. 74: “Take Me Home”

December 23, 2012

If you’re not in love with Sam and Amanda Jaeger after watching Take Me Home, promise me you’ll get professional help.

This 2011 film was written and directed by Sam Jaeger, who also plays the male lead. That character is Thom, a photographer who hasn’t been able to make a living with his art. He scrapes out a mean existence by illegally driving a New York City cab he bought at an auction, but even that is not enough to pay his rent, and he is evicted.

At this low point in his life, Thom meets Claire (Amanda Jaeger), a competent exec at a non-profit organization who discovers that her husband has been having an affair. This occurs almost simultaneously with news that her estranged father is seriously ill in California.

With her head spinning, Claire hails Thom’s cab, tells him to drive without a destination and then is surprised to find herself in eastern Pennsylvania. After the shock wears off, she tells Thom to take her to California, but stops in Las Vegas to visit her quirky but amiable mother, Jill, played by Lin Shaye.

Claire eventually learns that Thom is penniless and that being a legitimate cab driver isn’t the only thing he has lied about. And since she left home without plan or preparation, her own resources are dwindling. Stuck with each other, they more or less claw their way to their destination despite several delays, a potential felony, and one real disaster. The experience inspires both of them to think again about how they have been living.

As outrageous as the odyssey seems, this is a believable and visually interesting story, amusing and thought-provoking at the same time. All of the performances are subtle and effective, and the Jaegers are irresistable.