“No Vivaldi in the garage!” — Louie De Palma

May 20, 2011

Like everyone else, I suppose, I was very sorry to read that Jeff Conaway was comatose in a hospital in Encino. Conaway occupies a special pantheon in my family because of his role as Bobby Wheeler on the television series Taxi. Like some other entertainment media, television can do that for a person, throw at least one role his way that guarantees that his career will never be thought of as altogether ordinary.

Conaway was perfectly cast as the egotistical but insecure young actor, and he played the part in the midst of an ensemble of performers, many of whom were already experienced and all of whom were also perfectly cast. This fact, plus the excellent writing, made Taxi, one of the best situation comedies in television history.

There were 114 episodes of Taxi from 1978 to 1983, and every one was an artistic success. The series won 18 Emmy awards, a fact that speaks for itself.

The cast was remarkable: Judd Hirsch, Danny De Vito, Rhea Perlman, Christopher Lloyd, Andy Kaufman, Carol Kane, Marilu Henner, and Tony Danza. The selection of Danza was a particular stroke of genius. He was a prize fighter (9-3) when he was cast as boxer/cab driver Tony Banta and, although he had been type cast, he displayed impressive acting acumen, including pinpoint timing and a worthy double take, throughout the series.

Besides the regular cast, the producers imported outstanding guest players, including Julie Kavner, Barry Nelson, Louise Lasser, Jack Gilford, Ruth Gordon, Wallace Shawn, J. Pat O’Malley, Victor Buono, and Vincent Schiavelli.

A particular strength of the writers of Taxi was their ability to create unique characters – the nasty dispatcher Louie De Palma (De Vito), the dizzy immigrant Latka Gravas (Kaufman), the pickle-brained Jim Ignatowski (Lloyd), and the glowering Reverend Gorky (Schiavelli). The faux Eastern European language spoken by Latka, his wife Simka (Kane), Reverend Gorky, and Latka’s mother and cousin, was an ingenious and hilarious invention.

Taxi dealt with ordinary people with recognizable, ordinary problems, and in the context of its comedy it tastefully touched on sensitive topics such as bisexuality, blindness, old age, single parenthood, obesity, premenstrual mood disorders, drug addiction, and sexual harassment. Taxi’s writers never went for cheap laughs.

Taxi was similar to The Honeymooners in its heyday in the sense that it had a kind of grim realism. Until Jackie Gleason made the fatal error of moving the Kramdens and Nortons out of their tenement milieu, a haunting aspect of that show was the realization that those folks were never moving out of that neighborhood, Ralph and Ed were never leaving the bus company and the sewer system, no matter how hard they dreamed. The same thing was true of the characters in Taxi –ironically, with the exception of Bobby Wheeler– and the writers were faithful to that truth.

The last time I saw Arthur Laurents, he sat in the row in front of me during an opening at The George Street Playhouse — a theater where he felt very much at home. He was with several people who were at least six decades his juniors. Arthur had them in stitches; he told them one story after another and they hung on every word and then exploded in laughter.

The last time I saw Arthur Laurents, he sat in the row in front of me during an opening at The George Street Playhouse — a theater where he felt very much at home. He was with several people who were at least six decades his juniors. Arthur had them in stitches; he told them one story after another and they hung on every word and then exploded in laughter.

Arthur died yesterday at the age of 93, and I’m glad my last memory of him is the animated man with the sharp-edged wit holding the attention of yet another generation.

I got to know Arthur through numerous encounters at George Street, whose impresario, David Saint, was his colleague and close friend. Arthur, a writer and director, introduced a couple of his more recent plays at George Street, and he was sometimes there just as a member of the audience.

I got to know Arthur through numerous encounters at George Street, whose impresario, David Saint, was his colleague and close friend. Arthur, a writer and director, introduced a couple of his more recent plays at George Street, and he was sometimes there just as a member of the audience.

Arthur was blunt, and some folks didn’t like him on that account, but in a world in which obfuscation is the norm, some of us found that refreshing – especially when his bluntness was directed at hypocrisy or intolerance of any sort.

As a friend and I were reminding each other this morning, Arthur had a knack for making every conversation seem personal — a quality not always found in people of his stature.

Arthur was blackballed during the McCarthy era, and he remained angry at his peers who had cooperated with the House Un-American Activities Committee — not the least of them being Elia Kazan, who had “named names.” But Arthur picked his spots. I bumped into him at George Street one day in 2003, and I mentioned that Kazan had died not long before. “Yes,” Arthur said. “He was a great director.”

Where have you gone, Carmen Miranda?

April 21, 2011

The allusion to Carmen Miranda on this week’s episode of “Modern Family” got us to thinking about her for the first time in recent memory. Our first reaction was to wonder how many people in, say, their 40s or less who were watching that show would have known who Carmen Miranda was. When she was in her heyday, there was no need to ask; she was very popular — with good reason — and she was very successful.

The allusion to Carmen Miranda on this week’s episode of “Modern Family” got us to thinking about her for the first time in recent memory. Our first reaction was to wonder how many people in, say, their 40s or less who were watching that show would have known who Carmen Miranda was. When she was in her heyday, there was no need to ask; she was very popular — with good reason — and she was very successful. Carmen Miranda was born in Portugal in 1909, but she grew up in Brazil. She began performing at an early age, although financial stresses on her family led her to a short-lived but profitable career as a milliner. She continued to pursue her musical career, though, and before she came to the United States in 1939, she was already established as a star on radio, recordings, and film. She ultimately made 14 Hollywood movies and at one point was the highest-paid woman in the industry. She also made occasional appearances in the variety-show format that was a staple in early American television.

Carmen Miranda was born in Portugal in 1909, but she grew up in Brazil. She began performing at an early age, although financial stresses on her family led her to a short-lived but profitable career as a milliner. She continued to pursue her musical career, though, and before she came to the United States in 1939, she was already established as a star on radio, recordings, and film. She ultimately made 14 Hollywood movies and at one point was the highest-paid woman in the industry. She also made occasional appearances in the variety-show format that was a staple in early American television. Carmen Miranda was subject to some criticism in Brazil during her lifetime on the grounds that she had become too Americanized and was presenting an inaccurate image of Brazilian culture. She was so upset by this evaluation of her work that she stayed away from Brazil for many years. Now, however, she is memorialized by museums in both Brazil and Portugal. She is also the namesake of Carmen Miranda Square at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Orange Drive, across from Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

Carmen Miranda was subject to some criticism in Brazil during her lifetime on the grounds that she had become too Americanized and was presenting an inaccurate image of Brazilian culture. She was so upset by this evaluation of her work that she stayed away from Brazil for many years. Now, however, she is memorialized by museums in both Brazil and Portugal. She is also the namesake of Carmen Miranda Square at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Orange Drive, across from Grauman’s Chinese Theater.“They can go to hell” — Mohamad al-Fayed

April 11, 2011

In the Capitoline Museum in Rome there is a bronze statue of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. This is the only complete bronze statue of a Roman emperor that still exists. It was erected while the old stoic was in office – 176 AD. The reason that there are no other bronze statues from that era is that it was routine in the fourth and fifth centuries to melt them down so that the metal could be used for other statues or for coins. Sic semper gloria, as the saying goes. Statues of the emperors were destroyed also because Christians — apparently with no regard for the historical curiosity of future generations — regarded them as offensive remnants of paganism. In fact, it is said that the statue of Marcus Aurelius survived because it was erroneously thought to be an effigy of the sort-of Christian emperor Constantine.

It has not been unusual for statues of great, or at least dominant, figures to be desecrated by unappreciative come-latelies. Just the other day, some Syrians who are impatient with the fact that they lack basic political and economic rights did insulting things to an image of their former president, Hafez al-Assad, affectionately known as the “butcher of Hama” because of an unpleasant incident in which he caused the deaths of from 17,000 to 40,000 people.

There was some unpleasantness of a different sort about 8 years ago concerning a statue erected in Richmond representing Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad. The statue reflects on Lincoln’s visit to the ruined city in April 1865 at the end of the Civil War. There were bitter protests by people who objected to the statue, apparently still not able to concede Lincoln’s conciliatory attitude toward the southerners whose treason brought on the war in the first place.

Meanwhile, there has been some statuary-related turmoil in England. The trouble isn’t about figures of Neville Chamberlain or Guy Fawkes or Edward VIII. No, the man at the center of the maelstrom is Michael Jackson. There are two new statues of Jackson in place in the UK, and both of them are getting the raspberry from some of Jackson’s fans.

One scuffle is about a statue of Jackson dangling his baby son out of a hotel window. The life-sized image — which the artist calls “Madonna and Child” — recalls the incident in which Jackson held his son Prince Michael II out of a window in Berlin in 2002 while hundreds of fans were gathered below.

The sculpture is by a Swedish-born artist named Maria von Kohler; it’s displayed in the window of a music studio in East London. Jackson’s fans — who apparently haven’t been lured away by any of Simon Cowles’ instant sensations — find the sculpture revolting. They see it as an part of a persistent campaign of slander against Jackson, who set the bar for slander rather high. Viv Broughton, chief executive of the music studio, has a different view. He called the sculpture a “thought-provoking statement about fame and fan worship.”

The other skirmish has been prompted by a statue of Jackson erected outside Craven Cottage Stadium in London. The stadium is the home of the Fulham Football Club, a soccer team. Mohamed al-Fayed — whose son Dodi died in the auto accident that killed Princess Diana — owns the football club. The elder Fayed was a friend of Jackson.

Art critics have had a field day with the statue and some of Jackson’s disciples have criticized it, too.

Fayed responded to the criticism with a certain delicacy: “If some stupid fans don’t understand and appreciate such a gift, they can go to hell.”

I’ve often thought, when I pass the statue of Vice President Garret Hobart in front of City Hall in Paterson, how melancholy he must be as hundreds of people pass him each day without a glimmer of recognition. On the other hand, he has nobody attacking him except the pigeons.

Talking baseball

March 10, 2011

But to put that story in context, Scolari told me that his father — attorney Art Scolari — had played baseball at East Side High School in Paterson (this would have been long before Joe Clark got there) and then was an All-American shortstop at Drew University. Paterson? I was born in Paterson. My dad, who was about 13 years older than Art Scolari, went to Central High School where he ran track — particularly relays — and later managed a semi-pro baseball team that played all around the Paterson area.

I haven’t told Peter Scolari this yet, but after our conversation, my web browser stumbled on a story in a 1939 issue of the old Daily Record of Red Bank, N.J., reporting that a teenager named Lawrence Mahoney, who was from Lincroft, had successfully defended his state horseshoe pitching championship for the fifth time in a row. It was no snap, according to the story: breathing down Mahoney’s neck was 15-year-old Art Scolari of Paterson. Mahoney was 9-0 in the tournament; Scolari was 8-1.

I could have talked about baseball all night — it’s one of my many excuses to talk too much — but I was at the George Street Playhouse in New Brunswick to talk to Peter Scolari about his current project, a production of Ken Ludwig’s new play, “Fox on the Fairway.” This play, with a golf theme, had its world premiere last year in Washington, D.C. It’s a farce, and that’s a word that sends up the skyrockets, because farce done badly — or even done “all right” — is a painful experience for an audience. I’ve been there. Scolari, who knows a lot more about it than I do, made that point: “I don’t like to see a farce in which folks do an okay job. I’ll watch ‘The Sunshine Boys’ or ‘The Odd Couple’ and have a great time if everybody does a ‘good’ job. If I go to a farce and everybody does a ‘good’ job, I think, ‘Why did you do this?’ ”

I’ve read Ludwig’s play, but reading farce is like reading a recipe. It lays out the parts and the moves, but it can’t even hint at the reality. I have also read at least one negative review of the Washington production, but the fact that a farce doesn’t work with one company doesn’t mean it won’t work with another. Ludwig, after all, is the author of “Lend Me a Tenor” and “Crazy for You,” both of which won him Tony awards. And Scolari knows a thing or three about playing comedy in general and farce in particular.

Scolari first drew national attention in 1980 when he co-starred with Tom Hanks in “Bosom Buddies,” a TV sit-com about two young men who dress in drag so they can live in a women-only hotel where the rent is dirt cheap and about what they can afford. The show, which lasted a couple of seasons, was indirectly inspired by the Billy Wilder movie “Some Like it Hot.” Since then, Scolari has put together a long resume of television and stage appearances, mostly in comedies, including 142 episodes of Bob Newhart’s second hit series, “Newhart.”

Talking to Scolari, who is witty, thoughtful, and articulate, was an entertainment in itself. If I weren’t aware that I was keeping him from his train after he had spent a full day of rehearsal, I would have prompted him to talk for another hour, just so I could listen. If I had had unlimited time and he had had unlimited patience, I would have steered him back around to baseball, because no sport lends itself to talk as well as baseball does, and my guess is that Scolari appreciates that as much as I do. I asked him which New York team he roots for now that he is living on the East Coast again after his sojourn in California. He could have simply said that he roots for the Yankees, but this wasn’t a guy answering questions. This was a guy talking baseball:

Thurman Munson, Yankees catcher, captain, All-Star, and MVP, was killed in a plane crash in 1979. He was 32.

“I follow the Yankees. I make no apologies about it, but they’re not the Yankees. For me the Yankees who owned my heart ended with the captain, with Thurman Munson. I never got over that, to be honest with you, as a fan. So you come back, and they’re your team, and they’re in the Bronx, and that’s really important — but it’s not quite the same.”

“We start and end with the family” — Anthony Brandt

January 31, 2011

Since I was a kid, I have been fascinated by instances in which multiple members of a family have worked in the same or similar fields. For example, the other day I heard an interview on WNYC radio with Louis Rozzo, a fish dealer who was making an argument for taking the trouble to buy fresh anchovies and sardines and other fish that are typically packed in oil and canned. The conversation was interesting enough, but a detail that resonated with me was that Rozzo is the fourth generation owner of F. Rozzo and Sons. I would have liked to hear more about that.

In a similar way, I like reading about people like the Delahanty brothers – five of them played major league baseball – or the Harrisons, who included a signer of the Declaration of Independence, a Virginia legislator and attorney general, two presidents of the United States, and two members of Congress. The five Marx Brothers have always interested me less for their comedy than for their family history, which started with their maternal uncle, Al (Schoenberg) Shean, who was a famous vaudevillian.

This topic has been on my mind because I had an opportunity recently to talk with actress Stephanie Zimbalist, who is soon to appear in a production of Frank Gilroy’s play “The Subject Was Roses” at the George Street Playhouse in New Brunswick. On her own, Stephanie Zimbalist has built a substantial resume of performances on television and on the stage. However, her family’s background in the performing arts goes back at least as far as her great-grandfather Aron Zimbalist, who was an orchestral conductor in Russia in the 19th century. Her grandparents were both outstanding classical performers whom I have admired since I was very young. Her grandfather was Efrem Zimbalist, a concert violinist whose name can be mentioned in the same sentence with Jascha Heifitz and Fritz Kreisler. Efrem Zimbalist was married to Alma Gluck (nee Reba Feinsohn), who was one of the most popular female vocalists of the early 20th century. My family had 78 rpm recordings by both of these artists — along with others — and, long before I understood their significance, I listened to them over and over again on our wind-up Victrola.

Alma Gluck, who was born in Romania, was a soprano who was on the roster at the Metropolitan Opera Company. She also had a substantial concert career and was one of the first serious artists to make phonograph records, and that greatly contributed to her fame. She made more than 170 recordings for Victor between 1911 and 1924, choosing songs from a wide variety of genres. She and her husband made at least 32 recordings together, and he had a long list of recordings of his own. Zimbalist was also a composer and the director of the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia.

Efrem Zimbalist and Alma Gluck were the parents of Efrem Zimbalist Jr. – Stephanie’s father – who is a popular film and television actor whose starring roles included the TV series 77 Sunset Strip and The FBI.

Stephanie Zimbalist justifably has a great deal of pride in this heritage. I found that she enjoys talking about Alma Gluck – who died before Stephanie was born – and is well schooled in her grandmother’s career. Stephanie told me — only half joking, I suppose — that she didn’t pursue a singing career because she didn’t want to weather comparisons with her grandmother. Still, Stephanie Zimbalist has a trained voice and has given some performances. Speaking about her grandmother, she told me, “Daddy said she would have loved me, but I don’t know. She was tough task master on him. She wanted him to be a doctor or an engineer, and he wanted to be a dancer or a gymnast.” But the musical gene apparently didn’t skip a generation with the actor, Stephanie said. “He says he knows very little about music, but he knows an awful lot. He studied orchestration at Curtis, and he’s written a lot of things; he’s written many many pieces of music.”

Stephanie Zimbalist’s mother, the former Stephanie Spaulding, died in 2007. Stephanie cares for her mom’s pet, an elegant long-hair dachshund named Scampi, who participated in our interview. I asked Stephanie what would be next in her career after her run at George Street, and she said, “Nothing. I don’t have a career. I just have bumps in the road. That’s probably why I’m doing good work these days, if I am doing good work. Nothing’s an agenda. I don’t do anything to see where it will take me. I just do it for the work. On my plate in my life right now is this sweet little thing” — a reference to Scampi, who was on Stephanie’s lap. “And then, my Dad is 92, God bless him, and doing very well, but I spend quite a bit of time with him, just to be there.”

A publicity shot for “77 Sunset Strip”: Roger Smith, left, as private detective Jeff Spencer; Efrem Zimbalist Jr., right, as Spencer’s colleague, “Stu” Miller; and Edd Burns as their protege, Gerald “Kookie” Kookson — the inspiration for the 1959 pop song “Kookie, Kookie, Lend Me Your Comb.”

The bigger they are . . . .

March 16, 2010

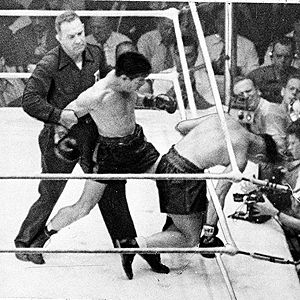

Once again the other morning, instead of getting up I clicked on the TV and turned to Turner Classic Movies. Never a good idea. We ended up watching “The Harder They Fall,” a 1956 movie starring Humphrey Bogart, Rod Steiger, and Virginia Mayo. It was Bogart’s last film; he died the following year.

“The Harder They Fall” was ostensibly based on the life of Primo Carnera, and if it was, it wasn’t meant as a compliment to the Italian boxer. The film concerns an Argentine giant who is brought to the United States by an unscrupulous promoter (Steiger) whose angle is to build up the unwitting and incapable kid through a series of fixed bouts and then bet against him when he fights for the heavyweight title. As far as I know there is no proof, but there is a persistent story Carnera was used in just that way.

The cast of “The Harder They Fall” included Jersey Joe Walcott, who won the world heavyweight title in 1951, when he was 37 years old. Walcott — who served as sheriff of Camden County and chairman of the N.J. State Athletic Commission — played a trainer in “The Harder They Fall,” and seemed comfortable in the part.

Also in this cast was Max Baer, who played the heavyweight champion who beat the Argentine kid and put an end to his career. This appears to have been a none-to-subtle reference to the fact that Baer took the title from the 275-pound Carnera in 1934. There is also an episode in this film in which the boxer played by Baer gives his opponent such a beating that the man suffers brain damage and dies. That, too, happened in Baer’s career: In 1930, a fighter named Frankie Campbell — brother of Dodger star Dolph Camilli — died after a bout with Max Baer in San Francisco.

Max Baer — father and namesake of the actor-director-producer who played Jethro in “The Beverly Hillbillies” — appeared in a couple of dozen movies and television productions. His brother, Buddy Baer — who was just as hard a puncher — had a record of 52 wins and 7 losses with 46 knockouts. He never won a title, but he had the distinction of once knocking Joe Louis out of the ring — in a fight that Louis ended up winning on a disqualification call. Baer claimed Louis had hit him and knocked him down after the bell ended the seventh round, and he refused to answer the bell for the eighth. Buddy Baer, too, appeared in numerous movies and television shows after he gave up boxing.

There were other personable guys who dabbled in entertainment after they were through in the ring, including Rocky Graziano and “Slapsie” Maxie Rosenbloom.

Graziano was a New York street brawler and thief who did time on Riker’s Island and spent lots of time in other sorts of incarceration and under the protection of the Catholic Church. He went AWOL from the Army after punching an officer, and he was suspended from boxing for failing to report an attempted bribe and again for running out on a bout. He was a very good boxer and immortalized himself in the annals of the sport for his three bloody fights with Tony Zale in 1946, 1947, and 1948. The second of those fights made Graziano middleweight champion of the world.

After his fighting career, Graziano — who, like a lot of guys with his background, was a charismatic figure — became a popular entertainer, especially on television comedies and variety shows.

Rosenbloom won the world light heavyweight title in 1932 and held it until 1934. On the one hand, his method of moving around the ring made it hard for opponents to land decisive blows, but that quality also meant that his fights often went the distance, and he took a lot of shots to the head. This eventually affected his physical health. Still, he capitalized on the image of a goofy pug and became a familiar figure on television. Although he wasn’t a serious actor, he played a significant role in Rod Serling’s “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” the iconic boxing story that starred Jack Palance and Ed and Keenan Wynn and included in its cast Max Baer.

In an interesting parallel, Primo Carnera, who was even more unlikely an actor than Rosenbloom, also hit one high note in a limited screen career. Carnera was a giant. When he defended his heavyweight title against Paolino Uzcudun, the two fighters weighed a total of 488 3/4 pounds — the most weight ever in a title match. And when he defended the title against Tommy Laughran, the average weight of the two fighters was 227 pounds, but Laughran weighed only 184. It was the biggest disparity ever in a title bout.

Carnera used his size and generally menacing appearance to his advantage in the 1955 film “A Kid for Two Farthings,” and he won critical approval for his portrayal of villainous wrestler Python Macklin.

The news that Marie Osmond’s son, Michael Blosil, has “committed suicide,” is unsettling, as such stories always are. What I find particularly sad about a person dying in that way is the loneliness that seems to be a necessary part of the context. I don’t even like the term “committed suicide,” because it evokes the notion that the person involved was ipso facto guilty of wrongdoing, whereas he or she was most likely making a solitary decision to end the torment of fear or confusion or sadness, or perhaps an indefinable feeling that made life unbearable.

I am shaken whenever I hear of someone taking his or her own life, and I had plenty of opportunities to be shaken in that way in more than 40 years of newspaper reporting. My mind almost involuntarily imagines the path that led that person from the potential with which most of us are born to the mental illness or physical ailment or poor choices or bad luck or combination of factors that made only death seem reasonable.

I went through that exercise when I heard of the death of the actress Brenda Benet in 1982. About a decade before, I had interviewed Brenda and her husband at the time, Bill Bixby. I was struck by how animated they were and especially how charged up they were about their lives together. They both talked at once, and he paced back and forth so vigorously that a couple of times he paced right out of the room and into the hallway. They had struck a balance, they told me, between the intimacy of their marriage and the independence of their separate careers, and they were almost defiant in proclaiming it — so much so, that I began my account of the meeting by writing, “You don’t interview Bill Bixby and Brenda Benet so much as you defend yourself.”

They had a child in 1974 and were divorced in 1980, and the child – a boy – fell suddenly ill and died in 1981. Brenda ended her own life in 1982. How alone she must have felt with her grief.

News of suicide also reminds me of Willard Hershberger, who died by his own hand — when he was 30 years old — two years and a month before I was born. I know of him because he belongs to a class of men who never die to memory — major league baseball players.

Hershberger, whose home town had the comforting name of Lemon Cove, California, had a distinction that he shared with only a few dozen others; he played for the 1937 Newark Bears. The Bears — who had no connection to the present team of that name — were a Yankees farm club and are reputed in baseball lore to have been the greatest minor league team ever. Their record that year was 109-43, and they finished 25 1/2 games ahead of Montreal. The lineup included Joe Gordon, Babe Dahlgren, George McQuinn, and Charlie “King Kong” Keller.

It must have been an exciting experience for Hershberger, a catcher, who appeared in 96 games that season and batted .325 on a team that collectively batted .299 for the season. He was already 27 years old when he made his major league debut with the Cincinnati Reds in 1938. He was the backup to Hall of Fame catcher Ernie Lombardi. During the 1940 season — with the Reds in contention for the National League pennant — Hershberger was standing in for Lombardi when the team lost games on July 31 and August 2. Hershberger picked up a buzz among the players that they would not have lost if Lombardi had been in the lineup. Hershberger was distraught, and he expressed himself to manager Bill McKechnie.

Hershberger evidently told McKechnie that he felt responsible for the losses, mentioned that his father had taken his own life about a ten years before, and intimated that he might make the same decision. This was a private conversation, but accounts say that the manager thought he had calmed the young man. But Hershberger didn’t appear before the next day’s game, and he was found dead in his hotel room.

He was a member of a team, but in the end he felt that failure was his alone. Linda Loman could have been speaking of Hershberger when she said of her husband: “Attention, attention must be paid to such a person,” and I’m sure McKechnie second-guessed himself every day after Hershberger died. But I have had the experience of trying to help such a person and found, in the end, that the loneliness can be intractable, insistent, and that’s the most frustrating and the saddest thing about it.

“The more he thought about it, the more his head hurt.” — George Ade

December 12, 2009

I was driving on the New Jersey Turnpike on my way to Manhattan a couple of weeks ago when I had an almost irresistible urge to buy an expensive watch. In fact, the urge was more specific than that; I wanted to buy an expensive watch from Fords Jewelers. This was an odd sensation for me because I haven’t worn a watch since 1956.

It turned out that this passing compulsion had been brought on by a billboard that promoted Fords Jewelers with an image of Tiger Woods showing a classy watch on his wrist. Woods hadn’t taken his plunge from Paradise yet, so naturally the message from this sign bored into my brain and made me want to be like Tiger — the cost be damned.

Fortunately, I was on my way to Carnegie Hall, so I had to continue on my way. After two and a half hours of Arlo Guthrie and his family, the urge had subsided and I continued telling time by the sun.

Now we read that advertisers that have been using Tiger Woods as their shill might be re-thinking the wisdom of it. Earlier this year, USA Today ran a story about companies having similar misgivings about continuing their relationships with Michael Phelps and Chris Brown.

Something about this doesn’t make sense to me. Do advertisers believe — or do they have evidence to show — that consumers actually buy products because of the celebrities who endorse them? Or, do advertisers rely on celebrities principally to call attention to the brands? And if that’s the case, wouldn’t it make sense to continue with a Tiger Woods, who is now the focal point of many people who — not being golf fans — normally would pay him no mind? “Hey, that guy is a schlemiel — but isn’t that a great-looking watch?”

Jerry Stiller and Ann Meara told me in an interview many years ago that they were circumspect about what they would endorse. They wouldn’t want their names connected with anything that could be construed as unsavory or embarrassing, and they would have to have at least some confidence in the quality of the product. Funny thing is, if Stiller and Meara suggested I buy something, I actually might listen.