Books: “Master of the Mountain”

August 22, 2012

My master’s thesis focused on an aspect of the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson. As a grad student at Penn State, I had access to the stacks at Butler Library in order to do some of the research. That would have been a good thing for a person with singleness of purpose, but not for an undisciplined scholar like me. The route to the “Jo” section of the stacks took me through the “Je” section, where I frequently stopped to browse through the papers of Thomas Jefferson. I have always found his intellect irresistible, and he has had an important influence on my writing. Accordingly, my research in the “Jo” section took a lot longer than it should have.

Jefferson, of course, had his flaws, just as we all do. His biggest one, unfortunately, ruined the lives of hundreds of people over several generations — the people he held in slavery, this herald of equality for “all men.”

That’s the topic of Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves,” a book by Henry Wiencek scheduled for publication in October.

Jefferson, by Wiencek’s account, carefully constructed a society of slaves to do the work at Monticello, Jefferson’s plantation estate in Virginia. Those slaves, like slaves on many other properties in that era, were arranged in a sort of hierarchy based on several factors: Jefferson’s assessment of their potential, the nature of the work they were consigned to, and their relationship to Jefferson. That’s “relationship” in the literal sense, because many of Jefferson’s slaves had a family connection to his wife, Martha. That relationship originated in a liaison between Jefferson’s father-in-law, Thomas Wayles, and one of his slaves, Betty Heming. There were several children born of that relationship and the whole lot, Betty included, became Jefferson’s property when Wayles died. One of those children was Sally Hemings, with whom, Wiencek and many others believe, Jefferson himself was intimate long after Martha Jefferson had died. That subject has gotten a lot of attention in recent years as researchers have tried to determine with certainty whether or not Jefferson fathered children with Sally Hemings. Wiencek presents arguments on both sides but is convinced by the evidence in favor of paternity, including contemporary accounts of household servants bearing a striking resemblance to the lord of the manor himself.

Sexual relationships between masters and slaves were commonplace. If Jefferson and Sally Hemings had such a relationship it would not be nearly so remarkable as the fact that Jefferson owned slaves at all. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Tommy J wrote that. He also publicly denounced slavery and mixed-race sexual relations and argued for emancipation and citizenship for black Americans. He simply didn’t apply those principles to his own life and “property.” Privately he argued — although he knew from the achievements of his own slaves that he was lying — that he didn’t believe black people were capable of participating in a free society, that they were, in fact, little more than imbeciles. He compared them to children. Wiencek writes and documents that Jefferson once even privately speculated that African women had mated with apes. (CP: Mr. Wiencek points out in his comments below that Jefferson made this observation publicly.)

Perhaps Jefferson was trying to make himself feel better about his real motive for keeping people in bondage: profit. He had meticulously calculated what an enslaved human being could generate in income, and it was enough for a long time to allow him to live a privileged life, entertaining a constant train of distinguished guests and satisfying his own thirst for fine French wines, continental cuisine, and rich furnishings.

Jefferson wasn’t the only “founding father” to engage in this behavior. James Monroe, James Madison, and George Washington all kept slaves; Washington freed his only in his will. (CP: This is true but out of context, as Mr. Wiencek explains in his comment below.) It is often written in defense of such men that they had grown up in an atmosphere of slavery and were simply products of their time. That’s an idea that Wiencek debunks, both because Jefferson himself had so often excoriated the institution of slavery and because he had been urged by some of his contemporaries to free his slaves. In fact, Jefferson was upbraided by the Marquis de Lafayette, a hero of the American Revolution, who visited the United States in 1824 and bluntly expressed his disappointment not only that slavery was still in place but that Jefferson himself was still holding people in bondage.

Wiencek also reports that at the request of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who also had participated in the Revolution, Jefferson assisted in the preparation of Kosciuszko’s will in which he left $20,000 with which Jefferson was to buy and free slaves. When Kosciuszko died, Jefferson refused to carry out the will.

Wiencek’s book is a good opportunity to take a close look at how slavery was constituted, how enslaved men, women, and children lived in Virginia in the early 19th century. But its real value is in stripping away the veneer that has been placed over men like Jefferson in an effort to legitimize modern political philosophy through a distorted view of the purity of their motives and personal lives.

Books: “John Quincy Adams”

August 3, 2012

A man of about my grandfather’s vintage was telling me that he once owned a house in Brooklyn and the candy store on the first floor. When I asked what had become of the property, he brought his hands together in a loud clap and said, “Mr. Hoover.” The implication was that he had lost the house and store as a result of the Great Depression and that the Great Depression was Mr. Hoover’s fault.

The history of the economic calamity of the 1930s is complex, and while Herbert Hoover’s approach to it is open to criticism, it is simplistic to argue that he was responsible for the losses suffered by millions of people. Unfortunately for Hoover, most Americans who can identify him at all are likely to describe him as the president who failed to solve the Depression. And that means that most Americans have forgotten — or more likely have never known — that Hoover was a great public servant and, in several instances, an American hero. As Casey Stengel said, you could look it up: Hoover organized the evacuation of Americans from Europe at the outbreak of World War I; he organized the delivery of millions of tons of food to Belgium after it had been invaded by Germany; he ran the commission that made sure American food supplies were conserved so that there would be enough to supply U.S troops in Europe during the war; he ran the administration that fed millions of people in Central Europe after the war; he oversaw the government response to the Great Mississippi Flood in six states in 1927; he organized a program that fed school children in impoverished occupied Germany after World War II; and under presidents Truman and Eisenhower he headed two commissions that successfully recommended reorganization and efficiencies in the federal government.

Hoover had his failings and even his dark side, but the country’s ignorance of his accomplishments — to say nothing of his long career as an engineer and businessman — is out of whack.

Hoover is not alone in this. John Quincy Adams’ legacy has suffered a similar fate, as Harlow Giles Unger explains in a biography of the sixth president that will be published in September. Adams’ presidency was a dud, but he otherwise led one of the most outstanding public lives in the history of the country. He was the son of brilliant parents — Abigail and John Adams — and they expected big things of him. Unger reports, in fact, that John Adams, the second president, expected his son to eventually follow him into that office, after getting a classical education and learning and practicing law. John Q. grew up in the midst of the American Revolution; in fact, he and his mother were eye witnesses to the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Defining events in his life, though, were successive trips to Europe with his father, who was engaged in diplomacy. Those trips led to a career in diplomacy for the younger Adams who was not excelled by anyone serving in that capacity before or since. He later served as secretary of state in the administration of James Monroe and again did outstanding work, including his authorship of what became known as the Monroe Doctrine. He was, Unger argues, one of the most important experts on foreign affairs in American history.

John Quincy Adams was elected to the presidency without campaigning for the office, and in a certain sense he wasn’t elected at all. The wildly popular war hero Andrew Jackson won more popular votes in the election of 1824 but not enough electoral votes to carry the day. Henry Clay threw the election into Adams’ lap by instructing the Kentucky delegation to vote for Adams, who had not won an electoral vote in that state. When John Q took office, he named Clay secretary of state, which was a much more powerful office then than it is now. Although it would have been out of character for Adams to have conspired with Clay in order to gain the presidency, that’s how many Americans read it, Unger writes, and it got Adams’ administration off to a poor start.

Adams had an ideal that would sound odd to Americans today: he believed that principle was more important than party. Tell that to John Boehner and Nancy Pelosi. Adams carried this idea to extremes, going to the mat first with his own Federalist party and then with the opposition Republicans on one issue or another. As a result, he really had no party, while Andrew Jackson was building the new Democratic party into a meaningful force. He also gave no thought to even conventional patronage when he appointed his cabinet, and so he was, as Jimmy Durante used to say, “surrounded by assassins.”

The short version is that Adams’ presidency didn’t amount to much, and he left office in a significant funk after losing the election to Jackson. But he was invited to run for Congress from a district in his native Massachusetts, and so he became one of three presidents to hold public office after leaving the White House. (The others were Andrew Johnson, who was elected to the U.S. Senate and William Howard Taft, who was appointed chief justice of the United States.)

Adams spent 17 years in the House of Representatives and it was, as Unger recounts in dramatic fashion, a wild scene. Adams hated slavery, which he had first seen up close when he traveled to Poland as a teenager. The House leadership didn’t want the subject broached in the chamber and passed rules to prevent the word “slavery” from being uttered or petitions against slavery from being presented. Adams fought furiously against this procedure, violating the rules repeatedly, and demanding over and over to know, “Am I gagged? Am I gagged?” He eventually became a highly respected figure in the House, even by those who disagreed with him, and reputedly was one of a handful of the best who ever served there.

During this period, Adams also got involved in the legal case of a group of more than fifty African men and women who were being transported as slaves from one port in Cuba to another when they seized control of the ship, the Amistad. The ship was taken into custody in American waters, and the Africans on board sued to keep from being returned to bondage.

Adams gave a seven-hour argument before the U.S. Supreme Court which, although most of the justices were hard-nosed southern slave holders, ruled unanimously that the Africans should be set free.

In recounting Adams’ career, Unger provides a close look into the life of the distinguished and patriotic Massachusetts family: the relationship between John Q. Adams and his redoubtable parents, and between John Q. and his wife, Louisa, who at times lost patience with the demands her husband’s public service made on family life.

Unger’s book brings this good and great man back to life at least on the printed page. It was a life that deserves much more attention than it gets.

Books: “The Longest Fight”

July 16, 2012

Prize fighting was part of my growing up.

My parents associated with some people who were connected to the boxing game: a promoter, a ring announcer, a cut man. At times, Mom and Dad would attend fights; I remember Mom coming home after one of those occasions with flecks of blood on her pink suit. Apparently they were at ringside.

In those days, the 1950s, we could watch fights on broadcast television, and we saw Carmine Basilio, Ezzard Charles, Jersey Joe Walcott, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Archie Moore.

Then, as now, I was a little schizophrenic when it came to boxing. I liked watching fighters like the ones I named, but I didn’t approve of boxing and thought it should be banned. I thought, and think now, that an enterprise in which the object is to knock your opponent senseless has no place in a civilized society.

Boxing was, in fact, illegal in most of the United States in the period discussed in William Gildea’s book, The Longest Fight. Where it was legal, one of the most prominent practitioners of “the sweet science” was Joe Gans, Gildea’s subject, the lightweight champion of the world and the first African-American to hold a world boxing title.

Gans held the lightweight title from 1902 to 1908 and he won the welterweight title as well in 1906. A native of Baltimore, he was strikingly handsome, well spoken, witty, courteous, and charming. Those qualities plus his nearly matchless skill in the ring attracted a large following, including white folks in numbers that were unusual for a black athlete in the days when Jim Crow was in such full vigor that racial epithets and garish cartoon figures of black Americans were commonplace in daily newspapers.

Gildea recounts that Gans put up with plenty of abuse during his career, but he had learned the wisdom of restraint, and he practiced it in and out of the ring. When a white opponent spat in Gans’s face while the referee was going through the ritual of instructions, Gans bided his time until the fight began. His demeanor in everyday life was disarming, and he won over many people who otherwise would have included him in their overall prejudices about black people.

Gildea reports that people such as promoters and managers took advantage of Gans, because they knew a black athlete had no recourse and often was risking his life just by climbing into the ring with a white boxer.

In what was arguably the biggest fight of Gans’s career — the “long fight” referred to in the title of this book — the manager of Oscar “Battling” Nelson insisted that Gans submit to three weigh-ins on the day of the contest, and under unheard of conditions. Gans just stood for it. No one, he knew, wins at the weigh-in.

That fight took place in September 1906 under a broiling sun in the Nevada desert town of Goldfield. Gans defended his lightweight title against Nelson, whom Jack London called “the abysmal brute” for both his free-swinging style and his penchant for dirty tactics like groin punches and head-butting. Nelson was also an unapologetic racist who made no bones about his revulsion for Gans and black people in general. It was a fight to the finish, and the finish didn’t come until the referee disqualified Nelson for a low blow in the 42nd round, after two hours and 48 minutes of combat.

By that time, Gans had beat the tar out of Nelson whose face, Gildea writes, was almost unrecognizable, but if Nelson had one positive attribute it was that he could take punishment, so he was still standing when the referee made Gans the winner.

Gildea describes the “fight to a finish” in episodes running through the book, interrupting the account from time to time to relate other aspects of Gans’s career and private life, including the two dives he acknowledged, his warm relationship with his mother, his romantic ties, his establishment of a Baltimore hotel and saloon that was a drawing card for a stylish crowd, both black and white, and his early death.

Gildea, whose carefully crafted narrative makes this book especially enticing, clearly explains the quality that made Gans a perennial winner. He blocked his opponents’ punches, moved as little as possible, threw a punch only when he saw an opening. And when he did punch, the blow was short and direct — in fact, Gildea writes, Gans introduced the technique of reaching out to touch his opponent and freezing the distance in his mind.

Gans is largely forgotten today, but as Gildea demonstrates, he was an important figure in the history of boxing and, more significantly, in the history of black citizens in the United States. Like the black men and women who were the first to venture into other fields, Gans took a barrage of slings and arrows for the team, and he did it with style.

And, what’s more, we’d do it again.

June 16, 2012

A phone rang in the newsroom at around 8:30 am, and the caller had a problem. He was a shift worker who got off a half hour before and had been in the nearby tavern long enough to get into, first, an argument and, second, a wager.

This was happening in Perth Amboy, long before the advent of the Internet or, for that matter, desk-top computers. The reporter taking the call was surrounded by mechanical Royal typewriters. But none of this context was of interest to the caller. He needed an answer, and he needed it soon. The question: “Is a giraffe’s tail as long as its neck?” There was money riding on the answer and, one suspected, paper money.

The reporter didn’t promise to resolve the question, but he did promise to call back one way or the other.

The home of the Perth Amboy Evening News, later The News Tribune, from 1923 until 1969. The present owner has preserved the name above the doors.

The reporter riffled through the meager reference materials in the newsroom but did not find the answer. With an air of futility, he called the nearby Staten Island Zoo, and located a person who provided information that may or may not have settled the wager. The giraffe’s neck is about six feet long. Its tail is about three feet long, but the tuft of hair at the end could double the length. The reporter called the pay phone at the tavern, repeated the data and hung up, praying that there were no weapons on the premises.

I recalled this incident the other day when I heard on National Public Radio that a listener had complained about a report on All Things Considered about a round of layoffs at a group of newspapers in the South. The listener wanted to know why the NPR news staff thought the layoffs of journalists was any more tragic than the layoff of anyone else. I didn’t hear the broadcast the listener was referring to, so I don’t know if the NPR staff exhibited some disproportionate sympathy for people of their kind, but the exchange reminded me of something I don’t hear much about in the reporting and commentary on the decline of newspapers in the United States.

A patch from The News Tribune, which was located in Woodbridge from 1970 to the mid 1990s. The patch is for sale on eBay.

The giraffe incident was a lighthearted example of the role local newspapers have played in their communities, a role that usually dealt with far more serious issues than animal anatomy.

The local newspaper was the last resort for many folks who were trying to settle wagers, finish their homework, or save their homes, their families, or their lives. There is no way to calculate the number of questions that were answered or problems that were solved by personnel at the newspapers that employed me for more than 40 years. Occasionally these matters resulted in stories; sometimes they were very big stories. But in countless instances, the news staff acted as exactly what it was, a surrogate for the public, and might spend hours or days or weeks wrestling with an issue that never generated a word in print. “You are the voice of those who have no voice,” one of my publishers once told me, and we all took that seriously.

The news staff, cumulatively, had skills, knowledge, and contacts that many people did not have. And in the days when newspapers had significant circulation and influence on public opinion, the voice of a journalist on the other end of the phone was, for many, especially those in public authority, vox Dei.

The news staff, cumulatively, had skills, knowledge, and contacts that many people did not have. And in the days when newspapers had significant circulation and influence on public opinion, the voice of a journalist on the other end of the phone was, for many, especially those in public authority, vox Dei.

The Home News Tribune, successor to The News Tribune of Woodbridge and the Daily Home News of New Brunswick.

But for those who called, whether readers or not, we constituted the only place to turn.

A friend once told me about a young woman, an immigrant, who was working in New York City as a translator. Her grandmother had come from the Old Country to visit her, and never went back. The grandmother’s visa had long since expired when she started to show signs of dementia. Because of the grandmother’s immigration status, the granddaughter was afraid to seek help but at the same time was afraid to leave her grandmother alone during the day. What, my friend wanted to know, did I intend to do about it? These folks had no connection to the newspaper; they lived in another part of the state. I called whom I needed to call and soon had a promise that the elderly woman’s immigration status would be normalized so that she could get the care she needed.

That’s one example. The women and men I worked with for four decades could contribute dozens, scores, of stories of that kind. I don’t know what will replace that resource, that safety valve —that friend who won’t turn away—in the life of a community.

A gift horse of sorts

May 24, 2012

KING RAMA IV MONGKUT

When I discussed the book I wrote about in a post here this week, I got an unexpected response from several people who thought I couldn’t distinguish a camel from an elephant.

The book was “The Last Camel Charge” by Forrest B. Johnson, which reports on an experiment in which the U.S. Army imported several dozen camels from North Africa in the 1850s to see if they would perform better than horses and mules in the difficult conditions in the American Southwest. In about a half dozen cases in which I started to discuss this book, my companion asked me if I didn’t mean elephants. In all of these cases, they were mixing up the episode Johnson wrote about with the incident in which the King of Siam offered to send elephants to the United States for use as beasts of burden.

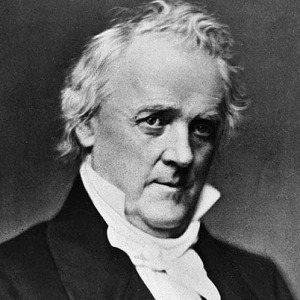

Most people who know about that offer heard about it in the musical play or the movie “The King and I,” in which, not surprisingly, it was badly distorted. In the movie and the musical, the King of Siam—Rama IV Mongkut—dictates, in English, a barely literate letter to Abraham Lincoln, offering to send the elephants. In reality, the king — who was fairly fluent in English — wrote such a letter, in his own hand, to Lincoln’s immediate predecessor, James Buchanan.

The king’s idea was that the elephants could be set free in the American wilderness and allowed to breed so that, as the herd grew, the animals could be captured and trained to carry cargo. Transportation being what it was in those days, that letter didn’t reach the White House until Buchanan had left office. So it was Lincoln who responded.

Lincoln, who signed the letter “your good friend,” wrote in part,

“I appreciate most highly Your Majesty’s tender of good offices in forwarding to this Government a stock from which a supply of elephants might be raised on our own soil. This Government would not hesitate to avail itself of so generous an offer if the object were one which could be made practically useful in the present condition of the United States.

“Our political jurisdiction, however, does not reach a latitude so low as to favor the multiplication of the elephant, and steam on land, as well as on water, has been our best and most efficient agent of transportation in internal commerce.”

From what I can tell, the portrayal of Mongkut in the stage show and the film was inaccurate in broader ways. While Yul Brynner, who created the role in both cases, represented the king as ignorant and in some ways boorish, Mongkut — a Buddhist monk and eventually an abbott — seems to have been well informed. He studied English, Latin, and astronomy and was an admirer of Jesus of Nazareth if not of Christian theological dogma.

Books: “The Last Camel Charge”

May 22, 2012

Samuel Bishop wanted to cross the Colorado River. Several hundred Mojave warriors objected. The factor that decided the argument: camels.

Forrest B. Johnson tells the story in his history “The Last Camel Charge.” It was April 1859, and Bishop’s friend and business partner — Edward “Ned” Beale — was leading a company of workers building a wagon trail between Arkansas and Los Angeles. The plan was for Bishop and a group of men from his ranch to rendezvous with Beale at the river and deliver supplies. But Bishop found his way blocked by Mojaves, whose people had lived in the region for a great many years. The Mojaves repelled Bishop’s first attempt to cross from California to the Arizona territory. After thinking things over, he hid the supplies, sent most of his men, wagons, and animals back to the ranch, leaving himself with 20 armed young men and 20 camels.

Camels? Six dozen of them had been imported from North Africa by the U.S. Army in an experiment championed by Jefferson Davis when he was a member of Congress and, during the administration of James Buchanan, secretary of war. The object was to determine if camels would be more serviceable than horses and mules in the punishing conditions in the American Southwest.

EDWARD BEALE

This experiment was carried on both by the Army and by civilians — namely Beale and Bishop. For the most part, it demonstrated exactly what its proponents expected. Camels could carry hundreds of pounds in excruciating heat without showing signs of fatigue. They would eat mesquite and cactus and almost any other vegetation that crossed their paths, whereas mules and horses required some form of grass. And, of course, camels could go for days without drinking, whereas desert travelers relying on horses and mules were frequently obliged to leave the trail and search for water to keep the animals alive.

Bishop had borrowed the camels from the Army. Now, although he was leading a troupe of civilians, he put them to military use. As he approached the river, he found an estimated 500 Mojave assembled there to deny him a crossing. He assembled his men, mounted on camels in four rows of five each. They galloped — likely at 40 miles per hour — directly into, and through, the ranks of the Mojave. Bishop crossed the river and didn’t lose a man.

In spite of all the evidence that camels were more suited than other animals to travel in the deserts of the Southwest, the experiment didn’t last very long after Bishop’s charge. There was a complex of reasons for that, not the least of which was the outbreak of the Civil War in 1860. Among other effects of the war was the departure of Jefferson Davis, camel proponent par excellence, from the federal government. Davis, of course, took up the secession cause and became president of the Confederacy.

In spite of the title of this book, camels aren’t the only subject Johnson covers.

The writer places the camels in the wild milieu that was the American West in those days. For example, he reports extensively on the conflict between the Mormons who had migrated to the Utah Territory to escape from the turmoil they had become embroiled in further east. When they were settling in Utah, they wanted to live on their own terms, and that brought them into conflict with the national government. At one point, while the Beale expeditions and the camel experiment were going on, President Buchanan, perhaps hoping to distract attention from the growing crisis over expansion of slavery into the western territories, declared the Mormons in rebellion against the United States and ordered the Army to deal with them— something, fortunately, that became unnecessary.

The writer also gives vivid accounts of the rigors encountered by folks traveling across country — the weather, the terrain, the hostile and violent people, not all of them natives.

Books: “Nixon’s Darkest Secrets”

March 30, 2012

There is a scene in a PBS documentary about Jack Paar that illustrates as well as anything why William Shakespeare would have loved Richard Nixon.

The scene comes from a 1963 episode of Paar’s groundbreaking talk show. Nixon, since leaving the vice presidency, had lost elections for president and for governor of California, but for a two-time loser, he was in a good mood — one might say light-hearted, a term not often associated with RMN.

Paar reminds the audience of something that was widely known at the time, namely that Nixon was a piano player. Paar also explained, to Nixon’s obvious amusement, that Nixon had also written some music for the piano and that his wife had made recordings of him playing his own tunes.

Paar said that bandleader Jose Meles had used one of those recordings to write an arrangement to back up one of Nixon’s compositions, and Paar asked Nixon to take to the keyboard.

Before complying, Nixon noted that Paar had asked earlier about Nixon’s political ambition. “If last November didn’t finish it, this will,” Nixon said, “because — believe me — the Republicans don’t want another piano player in the White House,” a reference to Harry S. Truman whose musical virtuosity was about on the same level as Nixon’s.

When I saw this incident on a PBS documentary about Paar, I thought about what a complex creature a human being is, and I thought about that again when I read Don Fulsom’s book, Nixon’s Darkest Secrets. Considering the depth and breadth of Nixon’s corruption and paranoia, I wouldn’t have thought it possible for a writer to do a hatchet job on the old trickster, but Don Fulsom has managed it.

On paper, at least, Fulsom has some credentials to be writing about this subject. He covered the White House and was Washington bureau chief for United Press International, which once upon a time was a viable news agency. Having been a journalist myself for more than 40 years, I would have expected a writer with Fulsom’s resumé, producing a book this long after Nixon’s death, to provide some insight into the whole man. As deeply immersed in muck as he was, after all, Nixon didn’t spend his whole time drinking himself blotto, assaulting people who annoyed him, beating his wife, raking in dough through his bag men, or plotting to have people like Jack Anderson killed.

On paper, at least, Fulsom has some credentials to be writing about this subject. He covered the White House and was Washington bureau chief for United Press International, which once upon a time was a viable news agency. Having been a journalist myself for more than 40 years, I would have expected a writer with Fulsom’s resumé, producing a book this long after Nixon’s death, to provide some insight into the whole man. As deeply immersed in muck as he was, after all, Nixon didn’t spend his whole time drinking himself blotto, assaulting people who annoyed him, beating his wife, raking in dough through his bag men, or plotting to have people like Jack Anderson killed.

And while his administration was forever besmirched by his prolongation of the Vietnam war and his order for the secret and murderous bombing of Cambodia, it was productive in many ways, including creation of the Occupational and Health Safety Administration , the National Endowment on the Arts, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Nixon approved the first significant step toward a federal affirmative action program. And Nixon — as probably only he could have — altered the course of modern history by changing the U.S. relationship with the Soviet Union and China.

Although Fulsom has riffled through some of the more recently released documents about Nixon, he hasn’t contributed anything to our understanding by recounting in nauseating detail the depravities of the man’s life. We get it. He was a sleaze. But he was also this other guy. This guy with a remarkable grasp of foreign affairs. This guy who supported a lot of moderate initiatives. And this guy who played the piano. And from this distance, that’s what’s so fascinating about him.

Look for Fulsom’s book with the scandal rags at the checkout counter. Shakespeare would have told the whole story.

You can see Nixon playing the piano on Jack Paar’s show by clicking HERE.

Books: “Eisenhower: The White House Years”

March 25, 2012

When I was a grad student at Penn State, former President Dwight Eisenhower visited the campus. It wasn’t a public event; he was speaking to a group of students from State College High School. But I was working in the public information office and found out about it and simply walked into Waring Hall at the appointed time. It was 1964 — a different era. Nobody asked who I was.

When I was a grad student at Penn State, former President Dwight Eisenhower visited the campus. It wasn’t a public event; he was speaking to a group of students from State College High School. But I was working in the public information office and found out about it and simply walked into Waring Hall at the appointed time. It was 1964 — a different era. Nobody asked who I was.

Eisenhower had been out of office for about four years. He was 74 and had suffered heart attacks and a stroke. Still, he stood at the edge of the stage with his head high and his shoulders back — in short, with the military bearing long associated with him. He encouraged those kids to take an interest in civic affairs and not to expect other folks to do all the work either inside or outside of government.

Eisenhower had been an iconic figure in our house, both because of his role in World War II and because he had kept the presidency out of Democratic hands for eight years.

Some of the family’s faith in Ike was well placed, even given the straight party-line mentality, but of course he was more complicated than he was portrayed around our place.

And, in fact, the Dwight Eisenhower that Jim Newton describes in Eisenhower: The White House Years is a complicated guy. While he was still in office, especially during his second term, he was often lampooned as an absentee president who golfed while the Soviets and Chinese plotted to conquer the world.

While it’s true that Eisenhower tried to fit golf and bridge into his routine, that characterization seemed ludicrous at the time, and Newton demonstrates well that it was fantasy. He shows that, on balance, Eisenhower’s administration, which kept the United States out of a shooting war for eight years, launched the interstate highway system and the St. Lawrence Seaway, and left the country with its last budget surplus until 1999, was an overall success.

Newton doesn’t discuss this in detail in this book, but Eisenhower’s achievements as supreme allied commander in Europe during World War II were in a significant way due to his firm but understated command as well as his personal diplomacy as he coordinated military officers and heads of state who had little or nothing in common except an enemy.

Similar qualities came into play when Eisenhower took on the presidency. He wasn’t inclined to the grand gesture, and his credo was what he called “the middle way,” meaning that on any issue he looked for the ground that was equidistant from extremes on either right or left.

Meanwhile, while Ike might have seemed like a man obsessed with cutting down on his slice, he was engaging in intense discussions concerning the rising belligerence of the Soviets and Chinese, more than once talking his military brass out of resorting to nuclear weapons. He was also overseeing covert activities undertaken by the CIA to overthrow foreign governments whose behavior was perceived as inimical to American interests — Iran and Guatemala among them. Eisenhower also made flight-by-flight decisions about high altitude surveillance of the USSR, and his administration was embarrassed when one of the planes was shot down and the pilot captured.

From our perspective, two of the most disappointing things about Eisenhower were his unwillingness to take the lead on civil rights for black citizens and his public silence about the demagoguery of Sen. Joseph McCarthy.

Eisenhower was content with the concept of “separate but equal,” and he was unhappy with the Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs the Board of Education. When the Board of Education in Little Rock, Arkansas, decided to obey the spirit of that ruling by admitting nine black teenagers to Central High School, there was immediately a crisis of authority as Gov. Orval Faubus, the Arkansas National Guard, and a howling white mob prevented the kids from entering. Eisenhower tried to finesse the problem by summoning Faubus to Washington and bargaining with him, but Faubus double-crossed Ike by withdrawing both the National Guard and himself from the scene. So Eisenhower was forced to do something distasteful to him, sending members of the 101st Airborne Division, with bayonets fixed, to escort the students into the school.

Eisenhower was content with the concept of “separate but equal,” and he was unhappy with the Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs the Board of Education. When the Board of Education in Little Rock, Arkansas, decided to obey the spirit of that ruling by admitting nine black teenagers to Central High School, there was immediately a crisis of authority as Gov. Orval Faubus, the Arkansas National Guard, and a howling white mob prevented the kids from entering. Eisenhower tried to finesse the problem by summoning Faubus to Washington and bargaining with him, but Faubus double-crossed Ike by withdrawing both the National Guard and himself from the scene. So Eisenhower was forced to do something distasteful to him, sending members of the 101st Airborne Division, with bayonets fixed, to escort the students into the school.

Eisenhower didn’t say or do anything publicly about McCarthy’s paranoid campaign of terror against real and imagined communists until the senator overreached and directed his venom at the U.S. Army. Then the president issued an order forbidding employees of the executive department from providing evidence to McCarthy’s committee.

Eisenhower’s reticence concerning McCarthy extended to the point that Ike let McCarthy pillory Gen. George Marshall, Ike’s mentor and possibly the man he most admired. Eisenhower ostensibly regretted that for the rest of his life, but the damage had been done.

Eisenhower’s reticence concerning McCarthy extended to the point that Ike let McCarthy pillory Gen. George Marshall, Ike’s mentor and possibly the man he most admired. Eisenhower ostensibly regretted that for the rest of his life, but the damage had been done.

Newton probably is a little easy on Eisenhower, but if he is, he’s easy on a man who led one of the most unselfish and productive lives of public service in American history, a life untouched by the personal and professional corruption and the blind partisanship that has affected major figures in American history before and after him.

The motto of Eisenhower’s election campaign — “I like Ike” — was particularly apt. He had his flaws as we all do, but the quality of his public service flowed to a large extent from his character: He was a nice man.

Books: “A Slave in the White House”

February 21, 2012

Folks confer a couple of lofty titles on James Madison, but “hypocrite” isn’t usually one of them. But Elizabeth Dowling Taylor isn’t bashful about using that term in her book A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons.

The subject of the book was born into slavery on Montpelier, Madison’s farm in Virginia, and remained in bondage until he was 46 years of age. Within the stifling confines of slavery, Jennings rose to the highest possible place, serving for many years — including the White House years — as Madison’s “body servant.” That meant that he attended to Madison’s personal needs — shaving him, for instance — and traveled with him pretty much everywhere. He also was often the first person a visitor encountered, and he supervised the other household staff in preparing dinners and receptions. Taylor surmises that Jennings, who was literate, paid a lot of attention to the conversations that took place when political and social leaders visited the Madisons.

One of the influential people Jennings became familiar with was Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, who served as a U.S. senator and as secretary of state. Madison had agreed, under pressure from a family member, to provide in his will that his slaves would be freed after specified periods. Madison — whose titles included “Father of the Bill of Rights” — reneged on that commitment and left about 100 slaves to his wife, with the provision that they would not be sold and that they would be freed at some point. When Dolley Madison began selling slaves in order to allay her financial problems, Jennings approached Webster, who had in the past assisted slaves. Webster arranged through a third party for Jennings to buy his freedom; Jennings worked for Webster for several years, and eventually, Webster took on the loan himself.

Jennings was the father of five; he married three times and was widowed twice. When he had satisfied his debt to Webster, he took a job in the Interior Department and worked there until a few years before his death in 1874. During the balance of his working life, he was a bookbinder.

Jennings also seems to have been something of an activist. The evidence Taylor had at her disposal suggested to her that even while he himself was a slave, he forged documents for others trying to get to free states and that after he had achieved his own freedom he was a player in the largest known attempt by slaves to escape to the North — 77 men, women, and children who tried to slip out of Washington via the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay.

The most dramatic incident that occurred during Jennings’ years as a slave probably was the invasion of Washington by British troops in 1814. By Taylor’s account, Jennings was one of the servants at the White House with Dolley Madison when the alarm came that the house had to be evacuated, and he evidently was among the small group that removed the life-sized Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington that now hangs in the East Room. The painting almost certainly would have been destroyed when the British ransacked and burned the mansion.

Taylor’s account of Jennings’ life provides a lot of insight into slavery in Virginia, which was a complex system governed by both necessity and tradition. Her book also explores the contradictory position in which Madison and his close friend, Thomas Jefferson, found themselves. Both men publicly acknowledged that human slavery was essentially evil and that it should be eliminated, but both men kept scores of slaves to labor on their behalf. They were openly berated for this by abolitionists in the United States and by visitors from abroad. The Marquis de Lafayette, for example, visited the United States in 1824 and told Madison and Jefferson that he was nonplussed to find that almost a half century after he had fought for human liberty in the colonies, two of the principal figures of the Revolution were still keeping human beings in bondage.

Madison gave what turned out to be only lip service to emancipation, insisting that while it was desirable, it was also more important to preserve the federal union. Madison also argued that any plan to emancipate slaves had to include a plan to remove them from the United States — probably to west Africa, where none of them had ever lived. His reasoning was that black and white Americans could not live together in peace, and he based that conclusion on his opinion that black people were a depraved race, lazy, profligate, and likely to resort to violence — an idea that apparently was not diluted by his long and close exposure to Paul Jennings, who was none of those things.