Books: “The Last Camel Charge”

May 22, 2012

Samuel Bishop wanted to cross the Colorado River. Several hundred Mojave warriors objected. The factor that decided the argument: camels.

Forrest B. Johnson tells the story in his history “The Last Camel Charge.” It was April 1859, and Bishop’s friend and business partner — Edward “Ned” Beale — was leading a company of workers building a wagon trail between Arkansas and Los Angeles. The plan was for Bishop and a group of men from his ranch to rendezvous with Beale at the river and deliver supplies. But Bishop found his way blocked by Mojaves, whose people had lived in the region for a great many years. The Mojaves repelled Bishop’s first attempt to cross from California to the Arizona territory. After thinking things over, he hid the supplies, sent most of his men, wagons, and animals back to the ranch, leaving himself with 20 armed young men and 20 camels.

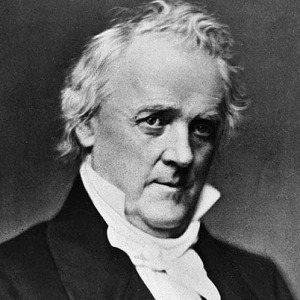

Camels? Six dozen of them had been imported from North Africa by the U.S. Army in an experiment championed by Jefferson Davis when he was a member of Congress and, during the administration of James Buchanan, secretary of war. The object was to determine if camels would be more serviceable than horses and mules in the punishing conditions in the American Southwest.

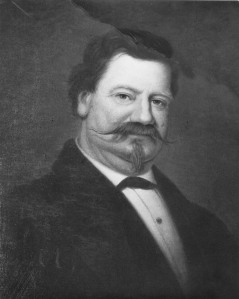

EDWARD BEALE

This experiment was carried on both by the Army and by civilians — namely Beale and Bishop. For the most part, it demonstrated exactly what its proponents expected. Camels could carry hundreds of pounds in excruciating heat without showing signs of fatigue. They would eat mesquite and cactus and almost any other vegetation that crossed their paths, whereas mules and horses required some form of grass. And, of course, camels could go for days without drinking, whereas desert travelers relying on horses and mules were frequently obliged to leave the trail and search for water to keep the animals alive.

Bishop had borrowed the camels from the Army. Now, although he was leading a troupe of civilians, he put them to military use. As he approached the river, he found an estimated 500 Mojave assembled there to deny him a crossing. He assembled his men, mounted on camels in four rows of five each. They galloped — likely at 40 miles per hour — directly into, and through, the ranks of the Mojave. Bishop crossed the river and didn’t lose a man.

In spite of all the evidence that camels were more suited than other animals to travel in the deserts of the Southwest, the experiment didn’t last very long after Bishop’s charge. There was a complex of reasons for that, not the least of which was the outbreak of the Civil War in 1860. Among other effects of the war was the departure of Jefferson Davis, camel proponent par excellence, from the federal government. Davis, of course, took up the secession cause and became president of the Confederacy.

In spite of the title of this book, camels aren’t the only subject Johnson covers.

The writer places the camels in the wild milieu that was the American West in those days. For example, he reports extensively on the conflict between the Mormons who had migrated to the Utah Territory to escape from the turmoil they had become embroiled in further east. When they were settling in Utah, they wanted to live on their own terms, and that brought them into conflict with the national government. At one point, while the Beale expeditions and the camel experiment were going on, President Buchanan, perhaps hoping to distract attention from the growing crisis over expansion of slavery into the western territories, declared the Mormons in rebellion against the United States and ordered the Army to deal with them— something, fortunately, that became unnecessary.

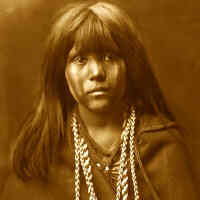

The writer also gives vivid accounts of the rigors encountered by folks traveling across country — the weather, the terrain, the hostile and violent people, not all of them natives.