Netflix Update No. 49: “Sabah”

July 10, 2011

The 2005 Canadian film Sabah has a lot to recommend it, but nothing more potent that Arsinee Khanjian, the actress in the title role.

The film concerns a family of Syrian Muslims living in Toronto. Sabah is an unmarried 40-year-old woman who is responsible for looking after her stylish but perhaps a little hypochondriac widowed mother. Unlike most of her family, Sabah wears drab traditional Muslim clothing — something that seems to symbolize the oppression she has been subjected to by her brother Majid (Jeff Seymour) since their father died. Majid wants Sabah at their mother’s side, and he monitors Sabah’s movements and finances as though he were her father.

In an unusual act of rebellion, Sabah — who loved to swim when she was a child — begins to surreptitiously visit an indoor pool in the city, despite her brother’s instruction that a Muslim woman is not seen in a bathing suit in public. At the pool, Sabah meets a secular Christian man, Stephen — played by Shawn Doyle — who is very courteous to her but also is clearly fascinated with the timid woman from their first encounter.

The poolside meetings evolve into a sweet romance, but Sabah’s insistence on keeping the relationship a secret from her family tries Stephen’s patience. Meanwhile, Majid’s young niece defies him by refusing to accept his choice of a husband for her, as Majid wrestles with a broader family problem that he has been keeping from his mother and siblings.

This movie — sort of an Abie’s Irish Rose for the 21st century — infuses the familiar challenge of intermarriage with a well-written script and thoughtful direction, both by Ruba Nadda, a Canadian of Arab ancestry. Our only reservation about the book was that the resolution of the family’s complicated problems was a bit too sudden — especially given the earlier intransigence of Majid.

The characters are all well played, and Doyle in particular deserves credit for the nuances and subtleties he brings to the person of Stephen. But Arsinee Khanjian, who was 45 when she made this film, is irresistible in the part of Sabah. The initial vulnerability, the glimpses of fire beneath a stoic exterior, and the thrill of her growing awareness of a wider world than she has ever known make Sabah an unusually attractive figure.

This film was well received when it was introduced, and those of us who are catching up to it late can see why.

Books: “No Regrets: The Life of Edith Piaf”

May 22, 2011

If it was Sunday night, I wanted to see Señor Wences. I did not want to see Edith Piaf, who turned up from time to time on Ed Sullivan’s TV show, “Toast of the Town.” It was all a part of being young and ignorant. I later learned to appreciate what an astounding singer Piaf was, but I knew nothing of her background before reading Carolyn Burke’s recent biography.

If it was Sunday night, I wanted to see Señor Wences. I did not want to see Edith Piaf, who turned up from time to time on Ed Sullivan’s TV show, “Toast of the Town.” It was all a part of being young and ignorant. I later learned to appreciate what an astounding singer Piaf was, but I knew nothing of her background before reading Carolyn Burke’s recent biography.

Piaf had a rough life in many respects. She was born in 1915 in a poor part of Paris to nearly indigent parents – her father an acrobat named Louis Gassion and her mother a drug-addicted street singer whose professional name, as it were, was Line Marsa. Louis and Line separated and Line played almost no part in Edith’s life except to occasionally surface and ask for money — which Edith usually provided. Louis took responsibility for his daughter, although that meant, for a time, that he left her to live in a brothel that was managed by his mother. He later reclaimed the girl and took her “on the road” with him — first while he performed with a circus and then when he returned to the streets. Edith had to work, keeping house, passing the hat when Louis performed on the street, and eventually singing for coins herself.

When she was 16, Edith convinced her father to let her live on her own, but she maintained a close relationship with him for the rest of his life, which eventually meant supporting him. As a result of one of the first of a very long string of romantic and/or sexual relationships, she bore a child, a girl, who died at the age of two — an experience that affected Edith for the rest of her life. She gradually developed as a singer on the street and in Paris dives, but her career took off after she was discovered by a shady character named Louis Léplee, who booked her in his cabaret and taught her some things about performing before the public. He also dubbed her “piaf” — “sparrow” — because of her stature (4’10”) and her bird-like gestures.

When she was 16, Edith convinced her father to let her live on her own, but she maintained a close relationship with him for the rest of his life, which eventually meant supporting him. As a result of one of the first of a very long string of romantic and/or sexual relationships, she bore a child, a girl, who died at the age of two — an experience that affected Edith for the rest of her life. She gradually developed as a singer on the street and in Paris dives, but her career took off after she was discovered by a shady character named Louis Léplee, who booked her in his cabaret and taught her some things about performing before the public. He also dubbed her “piaf” — “sparrow” — because of her stature (4’10”) and her bird-like gestures.

Edith Piaf specialized in chasons réaliste, songs of realism that expressed the sorrows of the lower class — including the prostitutes, beggars, and love-starved sailors who were among the singer’s earliest acquaintances. Frustrated love was a constant theme in these songs and in Edith Piaf’s life.

In addition to having a powerful and expressive voice, Edith Piaf was a prolific songwriter, creating the lyrics for many of the songs she introduced. Many of her love affairs were with men in whom she also had an artistic interest, and she played the mentor to them, demanding almost excruciatingly hard work but, almost without exception, helping them to solidify their careers. Edith herself became a star in several media in both hemispheres — night clubs, movies, records, radio, and television.

In addition to having a powerful and expressive voice, Edith Piaf was a prolific songwriter, creating the lyrics for many of the songs she introduced. Many of her love affairs were with men in whom she also had an artistic interest, and she played the mentor to them, demanding almost excruciatingly hard work but, almost without exception, helping them to solidify their careers. Edith herself became a star in several media in both hemispheres — night clubs, movies, records, radio, and television.

Edith Piaf lived in France during the World War II period, and was criticized in her own time by people who thought she was too accommodating to the German occupation. But Burke reports that the singer was instrumental in helping Jewish friends hide from the Nazis and that she irritated the Nazis, perhaps deliberately, by singing the work of a Jewish songwriter. But Edith was even bolder than that, by Burke’s account. She agreed to visit French soldiers who were being held in prisons in Germany, and she made a point of being photographed with them. Then she returned, as part of a plot by the French Resistance, and slipped some of those soldiers false identification that included their faces cropped from those photos. Some 188 of those men escaped, using those fake credentials.

Edith Piaf lived in France during the World War II period, and was criticized in her own time by people who thought she was too accommodating to the German occupation. But Burke reports that the singer was instrumental in helping Jewish friends hide from the Nazis and that she irritated the Nazis, perhaps deliberately, by singing the work of a Jewish songwriter. But Edith was even bolder than that, by Burke’s account. She agreed to visit French soldiers who were being held in prisons in Germany, and she made a point of being photographed with them. Then she returned, as part of a plot by the French Resistance, and slipped some of those soldiers false identification that included their faces cropped from those photos. Some 188 of those men escaped, using those fake credentials.

It’s an understatement to say that Edith Piaf didn’t take care of herself. She worked very hard, both in rehearsals and in a hectic schedule of bookings, partly because of the cost of maintaining not only her own lifestyle but also a coterie of friends, hangers-on, and just plain cheats, whom she deliberately cultivated as a sort of salon. She drank heavily and she became dependent on a complex of pain killers — for debilitating arthritis — sleeping pills, and uppers. This regimen apparently contributed to the ruin of her liver which in turn caused her death in 1963.

The poet Jean Cocteau — a close friend of the singer — described Edith Piaf as a genius and called her “this astonishing little person.” “A voice rises up from deep within,” he wrote, “a voice that inhabits her from head to toe, unfolding like a wave of warm black velvet to submerge us, piercing through us, getting right inside us. The illusion is complete. Edith Piaf, like an invisible nightingale on her branch, herself becomes invisible. There is just her gaze, her pale hands, her waxen forehead catching the light, and the voice that swells, mounts up, and gradually replaces her.”

The poet Jean Cocteau — a close friend of the singer — described Edith Piaf as a genius and called her “this astonishing little person.” “A voice rises up from deep within,” he wrote, “a voice that inhabits her from head to toe, unfolding like a wave of warm black velvet to submerge us, piercing through us, getting right inside us. The illusion is complete. Edith Piaf, like an invisible nightingale on her branch, herself becomes invisible. There is just her gaze, her pale hands, her waxen forehead catching the light, and the voice that swells, mounts up, and gradually replaces her.”

For a good example of that voice, click HERE.

I am troubled, for example, by the tags on Lipton tea bags. They’re flimsy and problematic. The design is ingenious enough. The tab is part of the envelope in which each tea bag nestles. In this respect, Lipton has it all over most brands, whose tea bags lie naked in the box. The envelope is perforated so that the user can detach the part that serves as the tag, but the envelope is made of such thin paper that the staple doesn’t grip the string very well, and as often as not the tag slips off. And that means that the whole string often winds up in the cup when the water is poured.

Most other brands — Wegmans and Twinnings, for instance — while eschewing the envelope, make the tags out of sturdier stuff.

It has occurred to me to call Lipton’s 800 number about this, but I had such an unsatisfying experience about a decade ago when I called Nabisco to complain about the way graham crackers are wrapped that I don’t have the heart to try it again.

It has occurred to me to call Lipton’s 800 number about this, but I had such an unsatisfying experience about a decade ago when I called Nabisco to complain about the way graham crackers are wrapped that I don’t have the heart to try it again.

There are two reasons why I don’t just drink another brand of tea. One is that Lipton tea is the only kind I like — at least, as compared to other ones that I have tried. Some people (you know who you are) sniff at this, implying that there is something pedestrian about Lipton and, therefore, about me, but that doesn’t move me. I have, to borrow a phrase from Jefferson Davis, “the pride of having no pride.”

The second reason I don’t switch brands is loyalty — not so much to the brand as to the salesman. When I was a kid, I was a devoted fan of Arthur Godfrey, who was a radio and television mogul back in the Bronze Age. Lipton was one of his sponsors and probably the one the public most associated with him. He pitched the tea and Lipton’s packaged soup. In those days before the highly produced commercials we see now, the host of a show often was the one who sold the products. Godfrey used to kid the sponsors; he might have been the first one who dared to do it. When he did his spiel for Lipton’s chicken soup, he used to assure the audience that a chicken had at least walked through the concoction.

The second reason I don’t switch brands is loyalty — not so much to the brand as to the salesman. When I was a kid, I was a devoted fan of Arthur Godfrey, who was a radio and television mogul back in the Bronze Age. Lipton was one of his sponsors and probably the one the public most associated with him. He pitched the tea and Lipton’s packaged soup. In those days before the highly produced commercials we see now, the host of a show often was the one who sold the products. Godfrey used to kid the sponsors; he might have been the first one who dared to do it. When he did his spiel for Lipton’s chicken soup, he used to assure the audience that a chicken had at least walked through the concoction.

Godfrey was troublesome. He was talented and bold as a showman, but he also was kind of full of himself, and many people my age and older might remember him best for having fired Julius La Rosa and several other regular members of his variety show cast — without warning, on live television.

Nobody’s perfect. I made a commitment to Arthur Godfrey that I would drink Lipton tea and no other, and I have been more loyal to him than he was to Julie La Rosa.

Nobody’s perfect. I made a commitment to Arthur Godfrey that I would drink Lipton tea and no other, and I have been more loyal to him than he was to Julie La Rosa.

Besides my one-sided deal with Godfrey, I might as well mention that I’m not happy when I don’t find a prominent portrait of Sir Thomas Lipton on the box of tea. Lipton, who founded the brand, was one of the great self-made businessmen of the latter 19th and early 20th centuries. I identify with him because he was a grocer, as were my father and grandfather. Of course, we had one store and Lipton eventually had about 300.

When Lipton got into the tea trade, he broke the established wholesaling patterns so that he could sell the product at low prices to the working poor. Lipton tea boxes used to feature a large picture of Thomas Lipton with a tea cup in his hand and a yachting cap on his head – an image that has been relegated to a tiny logo. Lipton was a yachting enthusiast and tried five times with five different yachts to win the Americas Cup. What he finally won was a special trophy honoring him as the “best of all losers.”

Lipton also did a lot to assist medical volunteers in Europe during World War I, including putting his yachts at the disposal of organizations transporting medical personnel and supplies and traveling himself to Serbia to show his support for doctors, nurses, and soldiers at the height of a typhus epidemic. Twinnings? I don’t think so.

John Surratt: On the lam in Rome and Alexandria

April 16, 2011

Maybe I’ve read too much about the plot against Abraham Lincoln; that may be why I can’t get up any enthusiasm about Robert Redford’s film “The Conspirator.” For more than 50 years, I’ve been wading through so many accounts either exonerating or condemning Mary Surratt for complicity in the crime, that I’m practically schizophrenic on the subject. I first took interest in the assassination when my dad subscribed to the Reader’s Digest condensed book series. The first book we got included a truncated version of Jim Bishop’s 1955 history The Day Lincoln Was Shot. Being a sucker for a sob story, my first inclination was to sympathize with Mrs. Surratt as an innocent victim of Edwin Stanton’s over-the-top response to the death of the president — which occurred, incidentally, 146 years ago this very day. I was about 14 when I read that book, and I think the idea of a woman being hanged superseded any calm analysis of the evidence.

Maybe I’ve read too much about the plot against Abraham Lincoln; that may be why I can’t get up any enthusiasm about Robert Redford’s film “The Conspirator.” For more than 50 years, I’ve been wading through so many accounts either exonerating or condemning Mary Surratt for complicity in the crime, that I’m practically schizophrenic on the subject. I first took interest in the assassination when my dad subscribed to the Reader’s Digest condensed book series. The first book we got included a truncated version of Jim Bishop’s 1955 history The Day Lincoln Was Shot. Being a sucker for a sob story, my first inclination was to sympathize with Mrs. Surratt as an innocent victim of Edwin Stanton’s over-the-top response to the death of the president — which occurred, incidentally, 146 years ago this very day. I was about 14 when I read that book, and I think the idea of a woman being hanged superseded any calm analysis of the evidence.

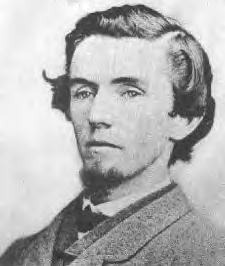

I’m probably more suspicious of Mary Surratt now than I was then, although I think the way the defendants were tried in that case was outrageous. Meanwhile, the most interesting figure in that case — well, the most entertaining, anyway — was Mary Surratt’s son John, whose story — as far as I know — has yet to be put on film. John Surratt was 20 years old at the time of the murder, and he had been active as a messenger and a spy for the Confederacy.

Surratt was involved with John Wilkes Booth in a conspiracy to kidnap Lincoln, take him to the Confederate capital in Richmond, and try to exchange him for southern war prisoners. That plot was unwittingly derailed by Lincoln, who changed the travel plans that the conspirators were relying on. It’s well established that Surratt wasn’t among the little circle of characters Booth enlisted after ramping his plan up to murder. But Surratt beat it out of the country as soon as the foul deed was done, leaving his mother behind to face the wrath of a seething Union. He may have been in upstate New York on a spying mission when Lincoln was killed. At any rate, he turned up in Canada and, after his mother had been hanged, he went to England, then to Paris, then to Rome. The unification of Italy hadn’t been completed yet, and John Surratt was able to enlist in the papal army and engage in combat with the forces of Giuseppe Garibaldi. According to Surratt, he wrote to an influential person in the United States to ask if it would be safe for him to return — by which he meant, would he be tried in a civil court or by an illegal court-martial like the one that had convicted his mother.

Surratt was involved with John Wilkes Booth in a conspiracy to kidnap Lincoln, take him to the Confederate capital in Richmond, and try to exchange him for southern war prisoners. That plot was unwittingly derailed by Lincoln, who changed the travel plans that the conspirators were relying on. It’s well established that Surratt wasn’t among the little circle of characters Booth enlisted after ramping his plan up to murder. But Surratt beat it out of the country as soon as the foul deed was done, leaving his mother behind to face the wrath of a seething Union. He may have been in upstate New York on a spying mission when Lincoln was killed. At any rate, he turned up in Canada and, after his mother had been hanged, he went to England, then to Paris, then to Rome. The unification of Italy hadn’t been completed yet, and John Surratt was able to enlist in the papal army and engage in combat with the forces of Giuseppe Garibaldi. According to Surratt, he wrote to an influential person in the United States to ask if it would be safe for him to return — by which he meant, would he be tried in a civil court or by an illegal court-martial like the one that had convicted his mother.

Although his correspondent advised him to stay away for three more years, Surratt decided to take his chances and go home. Before he could do so, however, someone in the Vatican recognized him, and Pope Pius IX ordered him arrested. Surratt was confined to a monastery on a mountain somewhere between Rome and Naples. Meanwhile the Vatican secretary of state informed the United States Secretary of State William Seward, and a man-of-war was dispatched from the Indian Ocean to fetch Surratt. When he was removed from his cell to be transferred to Rome, he broke away from his captors and dove over a wall onto a rock ledge about thirty five feet below. He was momentarily unconscious, but came to himself and scrambled down the mountainside to the village below. As he continued his flight, he fell in with a company of Garibaldi’s troops and told them he was an American deserter from the pope’s forces. They protected him until he departed for Alexandria, Egypt. There, he decided again that he should return to the United States, and he stopped disguising his identity. He was tracked down and arrested and sent home via Marseilles on the U.S. Navy sloop Swatara.

Although his correspondent advised him to stay away for three more years, Surratt decided to take his chances and go home. Before he could do so, however, someone in the Vatican recognized him, and Pope Pius IX ordered him arrested. Surratt was confined to a monastery on a mountain somewhere between Rome and Naples. Meanwhile the Vatican secretary of state informed the United States Secretary of State William Seward, and a man-of-war was dispatched from the Indian Ocean to fetch Surratt. When he was removed from his cell to be transferred to Rome, he broke away from his captors and dove over a wall onto a rock ledge about thirty five feet below. He was momentarily unconscious, but came to himself and scrambled down the mountainside to the village below. As he continued his flight, he fell in with a company of Garibaldi’s troops and told them he was an American deserter from the pope’s forces. They protected him until he departed for Alexandria, Egypt. There, he decided again that he should return to the United States, and he stopped disguising his identity. He was tracked down and arrested and sent home via Marseilles on the U.S. Navy sloop Swatara.

At home, Surratt got his wish, as it were, when he was tried for murder by a civil court in a proceeding that lasted from June 10 to August 10, 1867. The jury was divided — eight voting to acquit and four to convict — and Surratt was a free man. He lectured on his involvement in the Lincoln case without much success. He later became a teacher and eventually worked in the offices of a steamship company. He married, and he and his wife had seven children. He died in 1916.

At home, Surratt got his wish, as it were, when he was tried for murder by a civil court in a proceeding that lasted from June 10 to August 10, 1867. The jury was divided — eight voting to acquit and four to convict — and Surratt was a free man. He lectured on his involvement in the Lincoln case without much success. He later became a teacher and eventually worked in the offices of a steamship company. He married, and he and his wife had seven children. He died in 1916.

John Surratt is one of those captivating figures who flit around the outskirts of historical events which we sometimes think about only in terms of the major players. Judging by his previous relationship with Booth, this story probably would have been very different if Surratt hadn’t been out of town on April 14, 1865. As it is, he comes across as a scamp who makes good copy and probably would make an even better movie.

The text of one of Surratt’s lectures is at THIS LINK.

“They can go to hell” — Mohamad al-Fayed

April 11, 2011

In the Capitoline Museum in Rome there is a bronze statue of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. This is the only complete bronze statue of a Roman emperor that still exists. It was erected while the old stoic was in office – 176 AD. The reason that there are no other bronze statues from that era is that it was routine in the fourth and fifth centuries to melt them down so that the metal could be used for other statues or for coins. Sic semper gloria, as the saying goes. Statues of the emperors were destroyed also because Christians — apparently with no regard for the historical curiosity of future generations — regarded them as offensive remnants of paganism. In fact, it is said that the statue of Marcus Aurelius survived because it was erroneously thought to be an effigy of the sort-of Christian emperor Constantine.

It has not been unusual for statues of great, or at least dominant, figures to be desecrated by unappreciative come-latelies. Just the other day, some Syrians who are impatient with the fact that they lack basic political and economic rights did insulting things to an image of their former president, Hafez al-Assad, affectionately known as the “butcher of Hama” because of an unpleasant incident in which he caused the deaths of from 17,000 to 40,000 people.

There was some unpleasantness of a different sort about 8 years ago concerning a statue erected in Richmond representing Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad. The statue reflects on Lincoln’s visit to the ruined city in April 1865 at the end of the Civil War. There were bitter protests by people who objected to the statue, apparently still not able to concede Lincoln’s conciliatory attitude toward the southerners whose treason brought on the war in the first place.

Meanwhile, there has been some statuary-related turmoil in England. The trouble isn’t about figures of Neville Chamberlain or Guy Fawkes or Edward VIII. No, the man at the center of the maelstrom is Michael Jackson. There are two new statues of Jackson in place in the UK, and both of them are getting the raspberry from some of Jackson’s fans.

One scuffle is about a statue of Jackson dangling his baby son out of a hotel window. The life-sized image — which the artist calls “Madonna and Child” — recalls the incident in which Jackson held his son Prince Michael II out of a window in Berlin in 2002 while hundreds of fans were gathered below.

The sculpture is by a Swedish-born artist named Maria von Kohler; it’s displayed in the window of a music studio in East London. Jackson’s fans — who apparently haven’t been lured away by any of Simon Cowles’ instant sensations — find the sculpture revolting. They see it as an part of a persistent campaign of slander against Jackson, who set the bar for slander rather high. Viv Broughton, chief executive of the music studio, has a different view. He called the sculpture a “thought-provoking statement about fame and fan worship.”

The other skirmish has been prompted by a statue of Jackson erected outside Craven Cottage Stadium in London. The stadium is the home of the Fulham Football Club, a soccer team. Mohamed al-Fayed — whose son Dodi died in the auto accident that killed Princess Diana — owns the football club. The elder Fayed was a friend of Jackson.

Art critics have had a field day with the statue and some of Jackson’s disciples have criticized it, too.

Fayed responded to the criticism with a certain delicacy: “If some stupid fans don’t understand and appreciate such a gift, they can go to hell.”

I’ve often thought, when I pass the statue of Vice President Garret Hobart in front of City Hall in Paterson, how melancholy he must be as hundreds of people pass him each day without a glimmer of recognition. On the other hand, he has nobody attacking him except the pigeons.

Netflix Update No. 46: “Walk Don’t Run”

February 18, 2011

We watched the 1969 film “Walk Don’t Run,” which was notable for being Cary Grant’s last movie. He retired, so the story goes, because he realized that he could no longer pull off the leading man image and didn’t think his fans would accept him in supporting roles. So he was “retired” for 20 years, as far as the movies were concerned.

In “Walk Don’t Run,” Grant plays a prominent British businessman, Sir William Rutland, who visits Tokyo during the 1964 Olympic Games, arrives two days ahead of schedule and can’t find a hotel room. He spots a notice posted by someone wanting to share an apartment and goes to the address. The “someone” is Christine Easton (Samantha Eggar), a nervous young lady who is engaged to a supercilious employee of the British Embassy. She isn’t interested in sharing her apartment with a strange man, but Rutland ignores her protests, confuses her with the kind of fast talk that Grant was so good at, and moves in. Christine tries to make the arrangement as hard as possible on Rutland by imposing an impossibly tight schedule for use of the bathroom, but Rutland – though totally unable to keep up with the timetable – isn’t that easily dissuaded.

During a business call in Tokyo, Rutland meets brash American Steve Davis, who is a member of an American Olympic team — though he won’t say which one — and who also is without a place to stay until the Olympic quarters open. Davis is played by the ill-starred Jim Hutton. Rutland and Davis are at odds at first, but Rutland ends up subletting half of his room to Davis — without asking Christine, of course. She objects when she finds out, but she is no match for the two of them. Rutland, who is happily married and old enough to be Christine’s father, doesn’t like Christine’s fiancée and thinks Davis would be a better match for her. Therein lies the story, although there’s a subplot in which Davis is accused of being a spy.

This is a good-natured film, and the three principal actors do it justice. Grant was about 62 when he made this movie, and he hadn’t lost any of his appeal or energy.

The movie was shot on location in Japan, and that adds to its interest. Tokyo is a busy place, and the outdoor shots were done in the middle of the daily bustle.

This movie is based on a highly-regarded 1943 film, “The More the Merrier,” which I haven’t yet seen. That stars Charles Colburn, Joel Macrae, and Jean Arthur. It tells the same general story, but it takes place in Washington, D.C., and makes fun of the housing shortage there during World War II. Colburn plays the businessman, and he was widely praised for his performance. He and Grant were very different personalities, but I can picture Colburn playing the role.

Netflix Update No. 45: “Last Chance Harvey”

February 16, 2011

We watched the 2008 film “Last Chance Harvey” which stars Dustin Hoffman and Emma Thompson. Apparently this film attracted some attention when it was released, but I must have been out of town, because I don’t remember hearing about it. Hoffman and Thompson both got Golden Globe “best” nominations, so somebody was paying attention.

This movie got mixed reviews, but I’ll cast my lot with the yea-sayers.

Hoffman plays Harvey Shine, a song writer and musician who wanted to be a jazz pianist but settled for writing commercial jingles. Now that that industry depends far more on digital sound than on the black-and-whites, he’s having a hard time keeping up, so much so that his job is in jeopardy — hence the title of the film.

Meanwhile, Harvey is due to fly to London to attend the wedding of his daughter, Susan (Liane Balaban), who is tighter with her mom and stepfather than with Harvey, her dad. In fact, Harvey feels very much in the way at the dinner on the eve of the ceremony.

Meanwhile, the film follows the life of Londoner Kate Walker (Thompson), a lonely woman who works as a survey taker at Heathrow Airport. Despite a friend’s clumsy attempts to find her a match, Kate seems almost willingly trapped in a drab existence punctuated by constant phone calls from her aged and equally lonely mother.

OK, it’s obvious early on that Kate and Harvey are going to cross paths, but these characters are so well drawn by the actors, and their situations are so familiar, that it’s hard not to get interested in them. I read that Hoffman and Thompson had had a positive experience working together in a previous film and that Hoffman agreed to this role on the condition that he and Thompson ad lib some of their dialog. The relationship between them seems natural, so that strategy paid off.

Some viewers might be distracted by the age difference between Hoffman and Thompson — which is emphasized in a certain way by the difference in their heights — but there is no suggestion that their interest in each other is primarily sexual, or sexual at all, and the things that do attract them to each other make perfect sense. I, for one, am not cynical enough to dismiss the way Harvey’s personality is rejuvenated under the influence of a timid, self-conscious, but witty and intelligent woman. If one starts with the premise that Joel Hopkins’ script starts with — that both of their lives were at a dead end — the idea that they could form a relationship is both plausible and redemptive.

“Luckiest man on the face of the earth”

February 8, 2011

There’s a hilarious string of comments on the MSNBC web site stemming from a story about Lou Gehrig’s medical records. It’s entertaining to read these strings, because the readers who engage in them get upset and abusive – in this case, two of them sunk to assailing each other’s grammar – and then they get off on tangents and eventually go spinning off into space.

In this case, the brief story that started the row was about Phyllis Kahn, a member of the Minnesota State Legislature, who has introduced a bill that would open medical records after a person has been dead for 50 years, unless a will or a legal action by a descendant precludes it.

Kahn was inspired by a story that broke several months ago about a scientific study that speculated that the root cause of Gehrig’s death was concussions he suffered while playing baseball. Gehrig’s ailment, of course, was diagnosed as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, which affects the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord.

A study published last summer in the Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology made a connection between brain trauma and a form of ALS. Gehrig played first base, a position not usually associated with concussions, but he was hit in the head by pitches during his career, and he might have suffered head traumas in when he was the runner in a close play. He famously played for 14 years without missing a game, which means he played hurt many many times. In fact, although he is lionized for setting a record for consecutive games that stood until Cal Ripken Jr. surpassed it, Gehrig was criticized in some quarters in his own time by folks who regarded his streak as a foolish stunt and worried that he would damage his health.

Researchers want to look at Gehrig’s medical records, which are housed at the Mayo Clinic, and Kahn thinks they should be allowed to do so – and that, in the absence of instructions to the contrary, the records of any person dead for 50 years should be accessible. Gehrig has no descendants

As a Lou Gehrig fan, my emotions are screaming, “Leave the big guy alone!” As a former journalist, my interest in free flow of information is muttering that such records should become available at some point — though I don’t know what that point should be. Considering the level of concern about concussion injuries in football, research in this area could be valuable, and Gehrig might have provided an almost unparalleled opportunity to examine the impact of repeated injuries. His doctors might even have considered a link between his grueling career and the illness that killed him. The Mayo Clinic and a bioethics professor at the University of Minnesota are opposing this bill, probably concerned more about the opening of a flood gate than about Gehrig’s privacy in particular.

Incidentally, Phyllis Kahn, a Democrat-Farm-Labor legislator, once pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor for stealing campaign brochures distributed on behalf of a Republican candidate and replacing them with material for one of Kahn’s DFL compatriots. But that’s a story for another post.

Netflix Update No. 44: “Caramel”

January 27, 2011

When we visited Lebanon toward the end of the Clinton administration, the country was still occupied by the Syrian army. The occupation was a nuisance, because we frequently came across checkpoints where the cousin who was driving us around had to explain himself — or ourselves — to these interlopers. To bog things down a little more, the Lebanese army had its own checkpoints. Besides being an obstruction, the presence of the Syrians served as a constant reminder of the tense atmosphere that has too often prevailed in the country.

My maternal grandparents were born in Lebanon, and our principal reason for going there was to visit members of my grandmother’s family. Thanks to my cousin’s generosity with his time, we also saw a good deal of the antiquity and natural beauty Lebanon has to offer. Coming from a country that hadn’t had a war on its soil in well over a century, we couldn’t help being struck by the contrast between the competing armies with their automatic weapons and the Lebanese people going about their everyday lives.

That came to mind when we watched “Caramel,” a film made in Beirut, co-written and directed by Nadine Labaki, who also plays the central character, Layale. The story is about six women, three of whom work in a beauty salon, which is the axis around which the action revolves. The title, incidentally, refers to a sweet concoction used in the salon for hair removal; it actually figures in the plot in two instances.

The characters in the story are Layale, who is in a self-destructive relationship with a married man; Nisrine (Yasmine al Masri), who is about to be married to a man who doesn’t know of her previous sexual experiences; Rima (Joanna Moukarzel), who is attracted to other women – including Siham (Fateh Safa), a stunning customer at the salon; Jamale (Giselle Aouad), a frequent client at the salon, an aspiring actress who is having trouble coping with age; and Rose (Sihame Haddad), an elderly seamstress who cares for an unbalanced older sister, Lili, (Aziza Semaan), and is conflicted when she gets what apparently is her only chance at romance.

Labake — whose eyes, by the way, are hypnotic — tells the stories of these women with a loving, delicate, sometimes even dreamy touch. The blend of drama and comedy is just right. The performances, without exception, are credible and affecting. All of the characters, including the distracted Lili, are endearing and sympathetic.

The choice of settings adds to the quality of this film, because Labake keeps the camera’s eye on the story, and doesn’t go exploring the city for its attractive waterfront or its war-scarred ruins, or its slums. In fact, there are no allusions to the recent history of Beirut; this story is about the interior lives of these women.

An interesting cultural aspect of this story is that Nisrine is the only Muslim in the circle of friends; the other women are Christians. Nisrine’s family is very traditional — and, presumably, so is her fiancée, which is why — with the support and encouragement of her friends, she takes a drastic step to deceive her groom about her virginity.

The dialog in this film is in Arabic, and we watched it with English subtitles. It’s fun to listen to the actual dialog, because — as we noted when we visited there — the Lebanese mix French and English into their Arabic. This movie was well received when it appeared in 2007, and the attention was well deserved.