I’d know that voice anywhere

July 10, 2010

Somewhere, within the past few days, I saw the name “Ken Lynch.” It almost has to have been in the credits of a movie or TV show I was watching, but I can’t remember. Maybe I was dozing off at the time. It would not be unusual for me to have seen his name, because he appeared in about 175 television shows and movies — mostly TV. He frequently played a tough cop.

His name is not a household word, but I have been aware of him at least since I was 12 years old. I can recall that, because from 1949 to 1954 he had the title role in a detective series called “The Plainclothesman,” which was broadcast on the old Dumont network. I don’t remember when I started watching that show, but it could have been at the beginning, when I was 7, because Dad bought our first TV at Izzy Kaufman’s appliance store in ’49.

Television was new, and we had no context for it, so almost anything we saw was mesmerizing. I believe this cop show was especially so because of its unusual approach – namely, that the title character, known only as “the lieutenant,” never appeared on camera. The viewer, in effect, saw the story through the eyes of the lieutenant. Parenthetically — I suppose I could have just used parentheses — Dumont also had a detective series that ran from 1950 to 1954 in which one of the characters didn’t appear on camera. That series, which was broadcast live, was “Rocky King: Detective,” starring Roscoe Karns. At the end of each episode, Rocky King would talk on the telephone to his wife, Mabel, played by Grace Carney. Viewers would hear Mabel’s voice, but never see her face. Each show ended when Rocky hung up the phone and said, “Great girl, that Mabel!”

Possibly because the only impression I had of Ken Lynch was his distinctive raspy voice, I recognized it when I was watching an episode of “The Honeymooners,” a show that was very stingy about giving credit to actors other than the four stars. This occurred only a year or two after “The Plainclothesman” went off the air, but as sure as I was that we had finally seen “the lieutenant,” I couldn’t confirm it until much more recently.

In that episode, Ralph Kramden (Jackie Gleason) witnesses an armed robbery while playing pool with his sidekick, Ed Norton, and is afraid to tell police what he saw, because the robbers might retaliate. A detective comes to the Kramden apartment to question Ralph, and that detective is played by Ken Lynch. His voice, when he tells Ralph, “If you’re not a witness, you’re not entitled to police protection. And thanks — for nothin’!” is Lynch’s unmistakable file-on-metal sound.

Having no better way to exercise my brain cells, I wondered about that for decades. It was only the advent of the Internet and its seemingly inexhaustible resources that I was able to confirm that the invisible “lieutenant” was the visible cop in Bensonhurst.

Ken Lynch was born in Cleveland in 1910, and he died in Burbank in 1990. Oddly, despite his prolific career, Wikipedia doesn’t have an English language article on him, although there is one in French, but with no real biographical information. There is a short and descriptive profile of him on the International Movie Database web site, at THIS LINK.

Who is that woman?

June 15, 2010

At last, I know. I have been wondering for decades about an actress who had a brief role in an episode of “The Honeymooners,” and last night I found out by chance who she was.

The episode – one of the so-called “classic 39” – is a Christmas story in which Ralph Kramden saves money to buy Alice a present, but spends it on a bowling ball. Then he uses what money he has to buy a hairpin box that’s made of 2,000 match sticks glued together, believing the salesman’s story that the box came from the home of the Emperor of Japan. On Christmas Eve, before Ralph gives Alice this present, a neighbor – Mrs. Stevens – comes to the door and says she’s going to be away for the holiday and wants to give Alice a present before leaving. Of course, when Alice opens the package it’s a box just like the one Ralph bought, and the neighbor says she bought it at a novelty shop near the subway station.

The rest of that story doesn’t matter. What matters — to me, at least — is that I have always felt that the woman who played that small part was a wonderful actress. She created such a strong impression of Mrs. Stevens as warm and self-effacing that, even as a kid, I had a feeling that I’d like her to be my neighbor or even a member of my family — an aunt, maybe. Every time I see that episode, I’m entranced by that actress’s performance. But “The Honeymooners” producers were stingy with the credits, so the actress wasn’t identified.

So the other might I watched the 1949 version of “All the King’s Men” on TCM. The film is based on a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Robert Penn Warren, and it is the story of Willie Stark, a corrupt politician modeled after Huey Long. I had not seen it before, and the first time I heard the voice of the actress playing Stark’s wife, Sally, I knew my question had been answered. A little Googling confirmed that the Kramdens’ neighbor was portrayed by Anne Seymour.

Anne Seymour, it turns out, had an extensive career. The International Movie Database lists 121 film and television appearances for her between 1944 and 1988. “All the King’s Men” was her second movie. Her last was “Field of Dreams.” She played the newspaper publisher in Chisolm, Minnesota who helped Ray Kinsella learn about Dr. Archie “Moonlight” Graham.

The actress’s birth name was Anne Eckert, and her family was in the theater for at least seven generations dating back to the early 18th century in Ireland. Her brothers, James and John Seymour, were screen writers. Anne made her stage debut in 1928, and she later also worked in radio drama. Though she spent the bulk of her career working in television, she played Sara Delano Roosevelt, the mother of Franklin Roosevelt, in the 1958 Broadway production of “Sunrise at Campobello,” for which Ralph Bellamy won a Tony award for his portrayal of FDR. Although Anne Seymour got good review for her work in that play, she was not cast in the film version.

The bigger they are . . . .

March 16, 2010

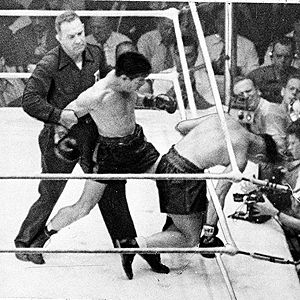

Once again the other morning, instead of getting up I clicked on the TV and turned to Turner Classic Movies. Never a good idea. We ended up watching “The Harder They Fall,” a 1956 movie starring Humphrey Bogart, Rod Steiger, and Virginia Mayo. It was Bogart’s last film; he died the following year.

“The Harder They Fall” was ostensibly based on the life of Primo Carnera, and if it was, it wasn’t meant as a compliment to the Italian boxer. The film concerns an Argentine giant who is brought to the United States by an unscrupulous promoter (Steiger) whose angle is to build up the unwitting and incapable kid through a series of fixed bouts and then bet against him when he fights for the heavyweight title. As far as I know there is no proof, but there is a persistent story Carnera was used in just that way.

The cast of “The Harder They Fall” included Jersey Joe Walcott, who won the world heavyweight title in 1951, when he was 37 years old. Walcott — who served as sheriff of Camden County and chairman of the N.J. State Athletic Commission — played a trainer in “The Harder They Fall,” and seemed comfortable in the part.

Also in this cast was Max Baer, who played the heavyweight champion who beat the Argentine kid and put an end to his career. This appears to have been a none-to-subtle reference to the fact that Baer took the title from the 275-pound Carnera in 1934. There is also an episode in this film in which the boxer played by Baer gives his opponent such a beating that the man suffers brain damage and dies. That, too, happened in Baer’s career: In 1930, a fighter named Frankie Campbell — brother of Dodger star Dolph Camilli — died after a bout with Max Baer in San Francisco.

Max Baer — father and namesake of the actor-director-producer who played Jethro in “The Beverly Hillbillies” — appeared in a couple of dozen movies and television productions. His brother, Buddy Baer — who was just as hard a puncher — had a record of 52 wins and 7 losses with 46 knockouts. He never won a title, but he had the distinction of once knocking Joe Louis out of the ring — in a fight that Louis ended up winning on a disqualification call. Baer claimed Louis had hit him and knocked him down after the bell ended the seventh round, and he refused to answer the bell for the eighth. Buddy Baer, too, appeared in numerous movies and television shows after he gave up boxing.

There were other personable guys who dabbled in entertainment after they were through in the ring, including Rocky Graziano and “Slapsie” Maxie Rosenbloom.

Graziano was a New York street brawler and thief who did time on Riker’s Island and spent lots of time in other sorts of incarceration and under the protection of the Catholic Church. He went AWOL from the Army after punching an officer, and he was suspended from boxing for failing to report an attempted bribe and again for running out on a bout. He was a very good boxer and immortalized himself in the annals of the sport for his three bloody fights with Tony Zale in 1946, 1947, and 1948. The second of those fights made Graziano middleweight champion of the world.

After his fighting career, Graziano — who, like a lot of guys with his background, was a charismatic figure — became a popular entertainer, especially on television comedies and variety shows.

Rosenbloom won the world light heavyweight title in 1932 and held it until 1934. On the one hand, his method of moving around the ring made it hard for opponents to land decisive blows, but that quality also meant that his fights often went the distance, and he took a lot of shots to the head. This eventually affected his physical health. Still, he capitalized on the image of a goofy pug and became a familiar figure on television. Although he wasn’t a serious actor, he played a significant role in Rod Serling’s “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” the iconic boxing story that starred Jack Palance and Ed and Keenan Wynn and included in its cast Max Baer.

In an interesting parallel, Primo Carnera, who was even more unlikely an actor than Rosenbloom, also hit one high note in a limited screen career. Carnera was a giant. When he defended his heavyweight title against Paolino Uzcudun, the two fighters weighed a total of 488 3/4 pounds — the most weight ever in a title match. And when he defended the title against Tommy Laughran, the average weight of the two fighters was 227 pounds, but Laughran weighed only 184. It was the biggest disparity ever in a title bout.

Carnera used his size and generally menacing appearance to his advantage in the 1955 film “A Kid for Two Farthings,” and he won critical approval for his portrayal of villainous wrestler Python Macklin.

Many years ago, I wrote a story about a group of college students who were fans of the “Honeymooners” television series. These students hadn’t been born in the 1950s when the show had its initial run, but they couldn’t get enough of it. Although I do the same thing with “The Honeymooners” and some other vintage shows, I asked them why they watched the episodes so often that they could recite most of the dialog, and they told me that the way the writers and actors used language was one of the things that fascinated them.

Fast forward to “Seinfeld,” which still holds my interest partly because of the way the writers and actors used language — for instance, a particular device, very New York to my ear, used to evoke comparisons. This phraseology was used seven times in the series — five times by Jerry speaking to George or Elaine, once by Helen Seinfeld speaking to Jerry, her son, and once by George, speaking to Elaine.

The one instance in which Jerry wasn’t the speaker occurred in the series premiere, “The Stakeout,” in which Jerry tries to flirt with a woman he meets at a dinner party, annoying Elaine, who is, in effect, his date at the party. The next day, when Jerry’s visiting mother tells Jerry that Elaine called while he was out, he asks, “What was the tone of her voice? How did she sound?” To which Helen replies: “Who am I — Rich Little?”

In the episode known as “The Jacket,” Jerry makes a reference to composer Robert Schumann, but mispronounces the name, putting the accent on the first syllable. George says, “Artie Schumann, from Camp Hatchapee?” To which Jerry answers, “No, you idiot!” And George says, “Who are you — Bud Abbott? Why are you calling me an idiot?”

In “The Trip,” in which Jerry invites George to accompany him on a trip to Los Angeles, George arrives at Jerry’s apartment with a big pile of luggage. Jerry looks at the bags and says: “It’s a three-day trip. Who are you — Diana Ross?”

In “The Revenge,” George plans to get back at the boss who fired him from a real estate firm by slipping the boss a “mickey” at the firm’s anniversary party. When George reveals this plan, the incredulous Jerry says: “Who are you — Peter Lorre?”

In “The Wink,” Elaine tells Jerry that she has agreed to go on a date with the man who calls from her wake-up service. Jerry says: “I still can’t believe you’re going out on a blind date.” Elaine answers: “I’m not worried. It sounds like he’s really good-looking.” To which Jerry answers: “You’re going by sound? What are we — whales?”

And in “The Limo,” Jerry and George find themselves in a limousine with two neo-Nazis who think George is their leader. George suggests that they extricate themselves by jumping out of the moving car. “We’re doing sixty miles an hour!” Jerry says. “So we jump and roll,” George explains. “You won’t get hurt.” And Jerry replies: “Who are you — Mannix?”

Finally, in the episode in which NBC president Russell Dalrymple gets food poisoning after Elaine sneezes on his pasta primavera, George has a tumultuous session with his counselor, Dana, played by Gina Hecht. During the session, Dana tells George that she read the script for a sit-com pilot Jerry and George have pitched to NBC, and she was not impressed. When George repeats this to his friends, Elaine — who recommended Dana — says, “Maybe she didn’t think it was funny,” to which George replies, “Oh, she didn’t think it was funny? What is she – Rowan and Martin?”

Who are you? Who am I? A very “exerstential” question, as Elaine Benes observed.

For a list of actual people referred to in “Seinfeld” scripts, click on THIS LINK.

“My mind is my own church” — Thomas Paine

January 17, 2010

In their learned discussion this week, political philosopher Glenn Beck and stateswoman Sarah Palin evoked the spirits of the “founding fathers” — a term, by the way, that was coined by an earlier genius, Warren G. Harding. After his own apotheosis of George Washington, Beck inquired of Gov. Palin, “Who is your favorite founder?” Apparently not wanting to offend the disciples of any one of our forbears, Gov. Palin demurred: “Ummm … you know … well, all of them.” Beck, clearly trying to uphold his reputation as a hard-hitting and objective interviewer, expressed his reservation by dismissing the governor’s attempt at delicacy as “bull crap” and demanded to know who was her favorite. The two great minds, as it turned out, were superimposed much like a prophetic convergence of heavenly bodies. Gov. Palin’s choice was George Washington. She made her reason clear: She empathized with Washington’s indifference to public office, except as a temporary duty, and his disdain for notoriety in general. So it was a natural choice for the former city council member, mayor, and governor, and unsuccessful candidate for lieutenant governor and vice-president — and recently engaged Fox News commentator. Neither Beck nor Palin brought up slave-holding or land speculation, but it was only a one-hour program.

Given the spiritual underpinnings of the two thinkers, their discourse naturally turned to religion. They agreed that religious faith was an important motivation for the “founding fathers,” although Glenn Beck darkly noted, “except Thomas Paine — we think he might have been an athiest.” As far as the others were concerned, Gov. Palin twice tried to assure Beck — who didn’t seem to be listening — that “we have the documents.”

Paine might have run afoul of Glenn Beck and Gov. Palin anyway inasmuch as he eventually described Washington with words like “hypocrite,” “apostate,” and “imposter.” However, unless the “we” who share Glenn Beck’s suspicions know something that historians do not know, Paine was not an athiest but a deist — deism being all the rage at the time, including among many of the “founders.”

As for the “documents” the governor referred as evidence that the republic somehow was founded on religious principles, perhaps she will be specific when she settles into her role as a commentator or when she publishes her next book. Presumably she is not referring to the Declaration of Independence, which is not part of the organic law of the land, nor such things as Thanksgiving proclamations. Nor can she mean the treaty with Tripoli, ratified by the Senate and signed by the deist founding father and president, John Adams — a treaty that explicitly rejects the idea that the government of the United States was founded on Christian principles. If Gov. Palin can find religion — except a prohibition against establishing it — in the federal Constitution, which is the law of the land, she has an obligation to expose it for the rest of us.

As for the “documents” the governor referred as evidence that the republic somehow was founded on religious principles, perhaps she will be specific when she settles into her role as a commentator or when she publishes her next book. Presumably she is not referring to the Declaration of Independence, which is not part of the organic law of the land, nor such things as Thanksgiving proclamations. Nor can she mean the treaty with Tripoli, ratified by the Senate and signed by the deist founding father and president, John Adams — a treaty that explicitly rejects the idea that the government of the United States was founded on Christian principles. If Gov. Palin can find religion — except a prohibition against establishing it — in the federal Constitution, which is the law of the land, she has an obligation to expose it for the rest of us.

Netflix Update No. 25: “My Louisiana Sky”

December 29, 2009

We watched a 2001 children’s movie from Showtime, “My Louisiana Sky,” and we weren’t surprised afterward to learn that it had won numerous awards — including the Andrew Carnegie Award and three daytime Emmys — and had been nominated for more.

Based on a novel by Kimberly Willis Holt, the story concerns Tiger, a 12-year-old girl, who lives on a farm in Louisiana with her mentally handicapped parents — Corinna and Lonnie Parker — and her maternal grandmother, Jewel Ramsey. Corinna (Amelia Campbell) is childlike, less mature now than her own daughter, and Lonnie (Chris Owens) is barely literate but is savvy enough to not only hold down a job on a nearby farm but to win the trust and respect of the owner. Jewel (Shirley Knight) keeps the house, maintains order, and does per-diem farm work — sometimes with the help of Tiger (Kelsey Keel), to earn some cash.

There is one prodigal family member — Jewel’s other daughter, Dorie, played by the redoubtable Juliette Lewis — who has left rural life behind for a career in Baton Rouge.

Tiger experiences isolation and rejection because of the way other children regard her parents. The only child who pursues a friendship with her is Jesse Wade Thompson (Michael Cera), and Tiger has trouble accepting his exuberance. When life at home deteriorates, she considers but does not leap at the prospect offered by Dorie of a comfortable and exciting life in the city.

While adults may find it simplistic, the portrayal of a girl deciding where her true happiness lies can be a valuable object lesson for children.

Under the direction of Adam Arkin — whose brother Anthony is married to Amelia Campbell — every cast member delivers a strong performance. Arkin and Kelsey Keel won two of the Emmys.

Say, who is that guy, anyway?

December 23, 2009

When we were watching the “Dragnet” Christmas episode the other night, a familiar face appeared. It was the clerk at a fleabag hotel. And as we do every time we see him, we said, “Wow, that guy must have made a thousand movies and TV shows.”

This time for a change, I decided to find out who he was, and he turned out to be character actor Herb Vigran. According to the International Movie Database, he appeared in 314 TV episodes and movies between 1934 and 1987. His last film, “Amazon Women on the Moon,” was released the year after his death.

Vigran held a law degree, but he never practiced law because he was in love with acting. Besides all the TV and movies, he did some stage work, including the 1936 Broadway classic “Having a Wonderful Time” with John Garfield and Eve Arden. He also worked in radio and was a regular on “The Jack Benny Program” before doing three years of military service during World War II.

His hundreds of TV jobs included multiple appearances on “The Adventures of Superman,” the original “Dragnet” and the later revival, “The Jack Benny Show,” “I Love Lucy,” and “Gunsmoke.”

He was so successful as a character actor that he had one of the most familiar faces in America — he looked like your Uncle Ed — but he rarely played the same part twice and was known to most of his audience as “Wotzisname.”

“To love at all is to be vulnerable” — C.S. Lewis

December 18, 2009

There are two things I still have to dig out in order to observe Christmas properly. One is the heirloom manger figures; the other is the DVD of the “Dragnet” episode in which the statue of the infant Jesus is stolen from a creche in a Los Angeles mission church. That’s the original 1953 version with Ben Alexander playing Frank Smith.

There are two things I still have to dig out in order to observe Christmas properly. One is the heirloom manger figures; the other is the DVD of the “Dragnet” episode in which the statue of the infant Jesus is stolen from a creche in a Los Angeles mission church. That’s the original 1953 version with Ben Alexander playing Frank Smith.

For the benefit of the uninitiated, LA detectives Joe Friday (Jack Webb) and Frank Smith are called to a church in a Latino neighborhood by Father Rojas because the statue has gone missing as the Christmas morning Masses are approaching. The poker-faced cops mechanically set about looking for the culprit, but have to return to the church on Christmas Eve to tell the priest that they have come up dry. While they’re standing with him near the sanctuary, they hear a racket coming from the direction of the front doors, and a little boy, Paco Mendoza, comes up the center aisle pulling the statue in a wagon. When the priest questions him in Spanish, the boy explains that he had promised that if he got a wagon for Christmas, Jesus would get the first ride. Frank Smith wonders aloud that the boy has the wagon already, before Christmas arrives. In one of the great exchanges in television history, the priest explains that the wagon didn’t come from the usual source; it was one of the toys refurbished by members of the fire department. “Paco’s family,” he tells the detectives, “they’re poor.” To which Friday, glancing at the Christ child back in its crib, says in his monotone: “Are they, Father?”

Our manger scene consists of white plaster figures, made in France, that belonged to my mother. She told me that she received the set from a Syrian priest when she was a child, and it wasn’t new then. Most of the figures have been broken and repaired one or more times, and one of the animals mysteriously disappeared about ten years ago. The set has a classic look to it, so we wouldn’t consider replacing it. It’s a few cuts above those translucent, illuminated plastic ones that have appeared on various lawns in the past week or so.

Our manger scene consists of white plaster figures, made in France, that belonged to my mother. She told me that she received the set from a Syrian priest when she was a child, and it wasn’t new then. Most of the figures have been broken and repaired one or more times, and one of the animals mysteriously disappeared about ten years ago. The set has a classic look to it, so we wouldn’t consider replacing it. It’s a few cuts above those translucent, illuminated plastic ones that have appeared on various lawns in the past week or so.

The tradition of assembling a manger scene — living or otherwise — originated in the 13th century with Francis of Assisi. The “Dragnet” crowd apparently wasn’t familiar with the tradition in which the image of the child is not placed in the manger until Christmas Eve, in time for the midnight Mass. A church like the one depicted in that episode would almost certainly have adhered to that custom. I have noticed that the child hasn’t been placed even in many of the lawn scenes that are out there now.

The child, of course, is the centerpiece of the feast, the vulnerable, innocent child who is both God and man in the belief of hundreds of millions of Christians. Why would God appear in human form — and as a newborn child? There is a learned and lovely reflection on this question on the blog “This Very Life,” written by Tania Mann in Rome. Those who are going to celebrate this holy day — and are very busy getting ready for whatever it implies for them — might want to spend a few minutes contemplating the reason for it all. If so, click HERE.

The child, of course, is the centerpiece of the feast, the vulnerable, innocent child who is both God and man in the belief of hundreds of millions of Christians. Why would God appear in human form — and as a newborn child? There is a learned and lovely reflection on this question on the blog “This Very Life,” written by Tania Mann in Rome. Those who are going to celebrate this holy day — and are very busy getting ready for whatever it implies for them — might want to spend a few minutes contemplating the reason for it all. If so, click HERE.

“. . . and in a manger cold and dark, Mary’s little boy was born” — Jester Hairston

December 15, 2009

One of the songs we listen to every year while we’re decorating our Christmas tree is “Mary’s Boy Child,” sung by Harry Belafonte, who first recorded it for an album in 1956. When it was reissued as a single, it reached No. 1 on the charts in Britain the following year. It was the first song to sell a million copies in England. Mahalia Jackson also recorded it in 1956. It has been covered by dozens of other artists ranging from the Maori soprano Kiri Te Kanawa to the disco group Boney M, which took it back to No. 1 in the UK in 1978.

It isn’t widely known, but this song was written by Jester Hairston — an unusually talented and versatile figure in American music and entertainment. Hairston (1901-2000) was a composer, songwriter, arranger, choral conductor, and actor. The grandson of slaves, he was born in North Carolina but lived from an early age outside of Pittsburgh. He graduated with honors from Tufts University and studied music at the Julliard School. His lifelong passion was for choral singing, and he conducted ensembles on Broadway and all over the world. In 1985, when such events were rare, he took the Jester Hairston Chorale, a multi-ethnic group, to sing in China.

Hairston did a lot of musical work for films. His most familiar work is probably the song “Amen” from the 1973 movie “Lilies of the Field” in which Sidney Poitier plays a young handyman who gets bamboozled into doing a lot of heavy labor for an order of German nuns in Arizona. Poitier won an Oscar for that performance, the first best-actor award to a black man. Poitier didn’t do any singing in that film, however. He lip-synched “Amen”; the voice was Jester Hairston’s.

Hairston had a lot of small roles in films — some of them demeaning, some without credit. He also appeared in the radio and television versions of “Amos ‘n Andy” — notably as Henry Van Porter, a high-end member of the Mystic Knights of the Sea lodge, which was the epicenter of much the action on the television series in particular. He also played Leroy, the brother-in-law of George “Kingfish” Stevens. More recent television audiences might remember Hairston for his role as Rollie Forbes in the series “Amen” that ran from 1986 to 1991.

You can hear Belafonte’s version of “Mary’s Little Boy” by clicking HERE. You can watch an amusing video HERE of Jester Hairston conducting a large choir in Odense in 1981 as they learn to sing the Christmas song in Danish.

There are interesting biographical notes about Jester Hairston HERE and HERE.