Books: “Master of the Mountain”

August 22, 2012

My master’s thesis focused on an aspect of the impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson. As a grad student at Penn State, I had access to the stacks at Butler Library in order to do some of the research. That would have been a good thing for a person with singleness of purpose, but not for an undisciplined scholar like me. The route to the “Jo” section of the stacks took me through the “Je” section, where I frequently stopped to browse through the papers of Thomas Jefferson. I have always found his intellect irresistible, and he has had an important influence on my writing. Accordingly, my research in the “Jo” section took a lot longer than it should have.

Jefferson, of course, had his flaws, just as we all do. His biggest one, unfortunately, ruined the lives of hundreds of people over several generations — the people he held in slavery, this herald of equality for “all men.”

That’s the topic of Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves,” a book by Henry Wiencek scheduled for publication in October.

Jefferson, by Wiencek’s account, carefully constructed a society of slaves to do the work at Monticello, Jefferson’s plantation estate in Virginia. Those slaves, like slaves on many other properties in that era, were arranged in a sort of hierarchy based on several factors: Jefferson’s assessment of their potential, the nature of the work they were consigned to, and their relationship to Jefferson. That’s “relationship” in the literal sense, because many of Jefferson’s slaves had a family connection to his wife, Martha. That relationship originated in a liaison between Jefferson’s father-in-law, Thomas Wayles, and one of his slaves, Betty Heming. There were several children born of that relationship and the whole lot, Betty included, became Jefferson’s property when Wayles died. One of those children was Sally Hemings, with whom, Wiencek and many others believe, Jefferson himself was intimate long after Martha Jefferson had died. That subject has gotten a lot of attention in recent years as researchers have tried to determine with certainty whether or not Jefferson fathered children with Sally Hemings. Wiencek presents arguments on both sides but is convinced by the evidence in favor of paternity, including contemporary accounts of household servants bearing a striking resemblance to the lord of the manor himself.

Sexual relationships between masters and slaves were commonplace. If Jefferson and Sally Hemings had such a relationship it would not be nearly so remarkable as the fact that Jefferson owned slaves at all. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Tommy J wrote that. He also publicly denounced slavery and mixed-race sexual relations and argued for emancipation and citizenship for black Americans. He simply didn’t apply those principles to his own life and “property.” Privately he argued — although he knew from the achievements of his own slaves that he was lying — that he didn’t believe black people were capable of participating in a free society, that they were, in fact, little more than imbeciles. He compared them to children. Wiencek writes and documents that Jefferson once even privately speculated that African women had mated with apes. (CP: Mr. Wiencek points out in his comments below that Jefferson made this observation publicly.)

Perhaps Jefferson was trying to make himself feel better about his real motive for keeping people in bondage: profit. He had meticulously calculated what an enslaved human being could generate in income, and it was enough for a long time to allow him to live a privileged life, entertaining a constant train of distinguished guests and satisfying his own thirst for fine French wines, continental cuisine, and rich furnishings.

Jefferson wasn’t the only “founding father” to engage in this behavior. James Monroe, James Madison, and George Washington all kept slaves; Washington freed his only in his will. (CP: This is true but out of context, as Mr. Wiencek explains in his comment below.) It is often written in defense of such men that they had grown up in an atmosphere of slavery and were simply products of their time. That’s an idea that Wiencek debunks, both because Jefferson himself had so often excoriated the institution of slavery and because he had been urged by some of his contemporaries to free his slaves. In fact, Jefferson was upbraided by the Marquis de Lafayette, a hero of the American Revolution, who visited the United States in 1824 and bluntly expressed his disappointment not only that slavery was still in place but that Jefferson himself was still holding people in bondage.

Wiencek also reports that at the request of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who also had participated in the Revolution, Jefferson assisted in the preparation of Kosciuszko’s will in which he left $20,000 with which Jefferson was to buy and free slaves. When Kosciuszko died, Jefferson refused to carry out the will.

Wiencek’s book is a good opportunity to take a close look at how slavery was constituted, how enslaved men, women, and children lived in Virginia in the early 19th century. But its real value is in stripping away the veneer that has been placed over men like Jefferson in an effort to legitimize modern political philosophy through a distorted view of the purity of their motives and personal lives.

Books: “The Longest Fight”

July 16, 2012

Prize fighting was part of my growing up.

My parents associated with some people who were connected to the boxing game: a promoter, a ring announcer, a cut man. At times, Mom and Dad would attend fights; I remember Mom coming home after one of those occasions with flecks of blood on her pink suit. Apparently they were at ringside.

In those days, the 1950s, we could watch fights on broadcast television, and we saw Carmine Basilio, Ezzard Charles, Jersey Joe Walcott, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Archie Moore.

Then, as now, I was a little schizophrenic when it came to boxing. I liked watching fighters like the ones I named, but I didn’t approve of boxing and thought it should be banned. I thought, and think now, that an enterprise in which the object is to knock your opponent senseless has no place in a civilized society.

Boxing was, in fact, illegal in most of the United States in the period discussed in William Gildea’s book, The Longest Fight. Where it was legal, one of the most prominent practitioners of “the sweet science” was Joe Gans, Gildea’s subject, the lightweight champion of the world and the first African-American to hold a world boxing title.

Gans held the lightweight title from 1902 to 1908 and he won the welterweight title as well in 1906. A native of Baltimore, he was strikingly handsome, well spoken, witty, courteous, and charming. Those qualities plus his nearly matchless skill in the ring attracted a large following, including white folks in numbers that were unusual for a black athlete in the days when Jim Crow was in such full vigor that racial epithets and garish cartoon figures of black Americans were commonplace in daily newspapers.

Gildea recounts that Gans put up with plenty of abuse during his career, but he had learned the wisdom of restraint, and he practiced it in and out of the ring. When a white opponent spat in Gans’s face while the referee was going through the ritual of instructions, Gans bided his time until the fight began. His demeanor in everyday life was disarming, and he won over many people who otherwise would have included him in their overall prejudices about black people.

Gildea reports that people such as promoters and managers took advantage of Gans, because they knew a black athlete had no recourse and often was risking his life just by climbing into the ring with a white boxer.

In what was arguably the biggest fight of Gans’s career — the “long fight” referred to in the title of this book — the manager of Oscar “Battling” Nelson insisted that Gans submit to three weigh-ins on the day of the contest, and under unheard of conditions. Gans just stood for it. No one, he knew, wins at the weigh-in.

That fight took place in September 1906 under a broiling sun in the Nevada desert town of Goldfield. Gans defended his lightweight title against Nelson, whom Jack London called “the abysmal brute” for both his free-swinging style and his penchant for dirty tactics like groin punches and head-butting. Nelson was also an unapologetic racist who made no bones about his revulsion for Gans and black people in general. It was a fight to the finish, and the finish didn’t come until the referee disqualified Nelson for a low blow in the 42nd round, after two hours and 48 minutes of combat.

By that time, Gans had beat the tar out of Nelson whose face, Gildea writes, was almost unrecognizable, but if Nelson had one positive attribute it was that he could take punishment, so he was still standing when the referee made Gans the winner.

Gildea describes the “fight to a finish” in episodes running through the book, interrupting the account from time to time to relate other aspects of Gans’s career and private life, including the two dives he acknowledged, his warm relationship with his mother, his romantic ties, his establishment of a Baltimore hotel and saloon that was a drawing card for a stylish crowd, both black and white, and his early death.

Gildea, whose carefully crafted narrative makes this book especially enticing, clearly explains the quality that made Gans a perennial winner. He blocked his opponents’ punches, moved as little as possible, threw a punch only when he saw an opening. And when he did punch, the blow was short and direct — in fact, Gildea writes, Gans introduced the technique of reaching out to touch his opponent and freezing the distance in his mind.

Gans is largely forgotten today, but as Gildea demonstrates, he was an important figure in the history of boxing and, more significantly, in the history of black citizens in the United States. Like the black men and women who were the first to venture into other fields, Gans took a barrage of slings and arrows for the team, and he did it with style.

“We are all brothers. . . .”

May 4, 2012

I gather from schnibles I’ve seen on the Internet that 30 Rock caught some flack for a parody of the 1950s television series Amos ‘n’ Andy. In the 30 Rock sketch, which was called Alfie and Abner, the characters were played by Tracy Morgan and John Hamm, who was in black face and an Afro wig, an image some folks found offensive. Somewhat incongruously — not to put too fine a point on it — the set was a replica of the Kramdens’ Bensonhurst kitchen rather than the most frequent Harlem scenes on Amos ‘n’ Andy — the Mystic Knights of the Sea lodge hall and the apartment of George and Sapphire Stevens.

The premise of the 30 Rock sketch was that one actor was in black face because NBC thought it would be too big a step to have two black actors on the stage at the same time. The irony is that Amos ‘n’ Andy, which had its original run from 1951 to 1953, was the first television series to have virtually an all black cast. White actors appeared in incidental roles in only a handful of episodes. I think it’s fairly well known that the show was driven out of production because of objections — most prominently from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People — on the grounds that it presented negative stereotypes of black Americans. It continued in reruns on some stations into the 1960s.

The television series evolved from a radio series that ran from 1928 until 1960. At the height of its success, Amos ‘n’ Andy was not only the most popular radio show on the air but the most popular diversion of any kind. And yet that series featured white actors mimicking black characters — namely Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, who created the show. For a while, Gosden and Correll performed all the male roles and some of the females. Later, other actors and actresses were cast in the supporting parts while Gosden and Correll continued to play the principal figures: Amos Jones, Andrew H. Brown, and George “Kingfish” Stevens. Gosden and Correll went a step further in the 1930 RKO movie “Check and Double Check,” donning black face to play Amos (Gosden) and Andy (Correll). Duke Ellington and his orchestra appeared in that movie.

The TV series is now controlled by CBS, which has withdrawn it from circulation and has at times taken legal action in an attempt to squelch the widespread Internet sale of bootleg tapes and DVDs of the episodes.

The Amos ‘n’ Andy television show is in a unique position, I think, in the sense that if it were judged in a vacuum — with no reference to who created it and when it first appeared — the conclusion might be different than it is when the show is viewed in its historical context. It was introduced when black American citizens in large numbers were still being denied their civil rights, when black people in many parts of the country were regularly threatened with violence, and when black people were freely lampooned in movies, cartoons, and minstrels. The show was still being broadcast in syndication in 1955, when Sarah Louise Keys, Claudette Colvin, and Rosa Parks in turn refused to give up their seats on the Montgomery, Alabama bus system to make way for white passengers. With Jim Crow making his last stand against legal equality and common decency, it shouldn’t have been surprising that black society and others would object to some of the characterizations on Amos ‘n’ Andy.

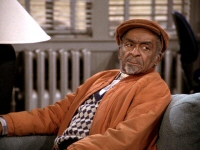

I have owned copies of all 78 known episodes of the series for many years, and I have watched them all several times and assigned students to write about them. I have also done a lot of research about the show itself and about the actors who appeared in it, and I have interviewed several people who were connected to it, including Nick Stewart who played Lightnin’ — the janitor at the lodge hall. Based on all that exposure, I think one can at least make the argument that, taken out of its milieu, Amos ‘n’ Andy would be no more offensive than all-black sitcoms that have appeared since, including Sandford and Son and Family Matters.

In fact, Amos ‘n’ Andy is fashioned on the same model as The Honeymooners. The rap on Amos ‘n’ Andy has been that it perpetuates stereotypes of black men as lazy, shiftless, and dumb, and of black women as shrewish and unattractive. As for the men, those characterizations apply to only four characters in the series: Andy Brown (Spencer Williams Jr.), George “Kingfish Stevens (Tim Moore), Lightnin’ (Nick Stewart, billed as Nick O’Deamus), and the lawyer Algonquin J. Calhoun (Johnny Lee).

These men live in a universe in which virtually everyone is black and, significantly, in which everybody but them is dignified, moral, and responsible. Just as The Honeymooners didn’t imply that all white men were naive schemers like Ralph Kramden or good-natured dumbbells like Ed Norton, Amos ‘n’ Andy didn’t imply that all black men were lummoxes, wasters, or charlatans. In both cases, the point was that the main characters were out of step with everyone around them; they were the exceptions, not the rules.

The most prominent female character on Amos ‘n’ Andy was Sapphire Stevens, the Kingfish’s wife. Sapphire was played by Ernestine Wade, who actually was a pretty woman. Sapphire longed for a more genteel life in which she wasn’t hounded by bill collectors and in which she could associate with folks a little more erudite and stimulating than Andy Brown. Wade portrayed her as a decent woman who was faithful to a husband who didn’t deserve it; if Sapphire nagged the Kingfish and at times lost her temper with him, no one could blame her any more than they could blame Alice Kramden from blowing up at Ralph.

Less sympathetic a character, perhaps, was Ramona Smith, Sapphire’s mother, who was presented as the classic bellicose battleship of a mother-in-law — an accessory the Kingfish had in common with Ralph Kramden.

The broadest of the regular characters were the shambling, drawling Lightnin’, and Calhoun, a loudmouth and a fake.

There was a shift in emphasis in the television series in which Amos, although a title character and often the voice that introduced the episode (“Hello, folks. This is Amos. . . .”), became a secondary figure, and the Kingfish became the focal point of almost every episode. In the TV series, Amos was a level-headed, intelligent, soft-spoken, man who owned his own taxicab and led a quiet life with his lovely wife, Ruby, and their two daughters. Amos was often the Jiminy Cricket to the Kingfish and Andy, giving them sound advice and sometimes directly getting them out of trouble.

An aspect of this show that is always overlooked is the quality of the cast it brought together. Many of the actors had long careers as entertainers, persisting through an era in which they were unappreciated, type cast, and often rudely treated.

Tim Moore, who played the chronically unemployed and finagling Kingfish, had a remarkable life as a vaudevillian, entertaining all over the world. He also appeared in several Broadway shows and in films. He was even fairly successful as a boxer. He was lured out of retirement to play the role in Amos ‘n’ Andy. His character’s sobriquet was actually his title as head of the lodge — the kingfish. When he wanted his pals to bail him out of some scrape, he often reminded them, “After all, we are all brothers in that great organization, the Mystic Knights of the Sea.”

Spencer Williams Jr., who played the sweet but gullible oaf Andy Brown, was an important figure in the history of American film. A World War I army veteran who worked in many aspects of the movie business, including as a sound technician, eventually became a writer, director, and producer of so-called “race movies,” films that were made specifically to be shown in segregated theaters. His film “Go Down Jesus,” which was made on a $5,000 budget and with nonprofessional actors, was one of the most successful “race films” of all time. Time magazine called it one of the “25 most important films on race.”

Alvin Childress, who played the sensible and gentle Amos Jones, held a bachelor’s degree in sociology. He began working as an actor with a Harlem theater company, and he worked on both the stage and on film. He appeared on Broadway as Noah in Philip Yordan’s play Anna Lucasta, which ran for 957 performances. Although he appeared in a couple movies and in episodes of Perry Mason, Sandford and Son, Good Times, and The Jeffersons, Childress, who felt he had been typed by casting directors as Amos Jones, had a hard time sustaining his career. His first marriage, which lasted for 23 years, was to a well known writer and actress, Alice (Herndon) Childress.

Nick Stewart, who played Lightnin’, was a dancer and comedian who appeared in night clubs, Broadway shows, films, and radio. Stewart was the voice of Br’er Bear in the 1946 Disney movie Song of the South. In 1950, He and his wife, Edna, founded the Ebony Showcase Theater in Los Angeles, where for many years they provided a venue in which black actors could appear in quality productions.

Johnny Lee, who played the blustering, incompetent lawyer, Algonquin J. Calhoun, was a dancer and actor who appeared in a couple of dozen films and television shows, perhaps most notably as the voice of Br’er Rabbit in Song of the South. He had featured roles in Come On, Cowboy! (1948) and She’s Too Mean for Me (1948) and he played a stuttering bill collector in Boarding House Blues (1948). He also starred in an all-black musical comedy, Sugar Hill, at the Las Palmas Theatre in Hollywood in 1949. His last TV role was Mr. Gibbons the Locksmith on Dennis the Menace in 1963.

In addition to these regular players, Amos ‘n Andy provided occasional roles for some very talented actors, including the sisters Amanda and Lillian Randolph. Amanda Randolph, who played Ramona Smith, mother of Sapphire Stevens, was the first black actress to appear on a regularly-scheduled network television show. That was The Laytons, which appeared on the old Dumont network for two months in 1948. She was an exceptional jazz pianist and a composer. She appeared in New York musicals, entertained in Europe, performed in vaudeville, and cut records as both a musician and a vocalist. She appeared on Broadway, in films, and on radio. On radio, she played the title role in Beulah in the 1953-1954 season, inheriting the role from Lillian.

She was the first black American actress to have her own daytime network TV show — Amanda, which ran on Dumont in the 1948-49 season. Among her many TV roles was Louise, the wisecracking maid on Danny Thomas’s comedy series.

Lillian Randolph, who appeared in Amos ‘n’ Andy as Madame Queen, a former girlfriend of Andy Brown, was also a multi-talented performer on radio, television, and film. She had played Madame Queen on the radio, too, and made the character’s name a household word in the United States. She played the maid Birdie Lee Coggins in The Great Gildersleeve radio series, and she repeated the role in Gildersleeve films and the later TV series. Her performance of a gospel song on the TV series led to a gospel album on Dootone Records. She also made regular appearances on The Baby Snooks Show and The Billie Burke Show on radio. Her best known film roles probably were Annie in It’s a Wonderful Life and Bessie in The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer. Her television roles included Bill Cosby’s mother on The Bill Cosby Show, and Red Foxx’s aunt Esther on Sandford and Son. Altogether, she appeared in about 93 movie and television properties. In 1954, Lillian Randolph became the first black member of the board of directors of the Hollywood Chapter of the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.

One of the most eminent persons to appear on the Amos ‘n’ Andy TV series was Jester Hairston, who made occasional appearances as both Sapphire’s brother Leroy and as wealthy and dapper lodge member Henry Van Porter. Although he appeared in about 20 films and several TV shows, acting was secondary to Hairston’s career as a composer, songwriter, arranger, and choral conductor. He wrote the song “Amen” for the 1963 film Lilies of the Field and he dubbed the song for Sidney Poitier to lip-sync. He also wrote the Christmas carol Mary’s Little Boy Child. Harry Belafonte’s recording of the song reached No. 1 on the charts in the UK in 1957. From 1986 to 1991, Hairston played Rolly Forbes in the TV series Amen.

Hairston was a graduate of Tufts University, and he studied music at the Julliard School. He was highly regarded as a conductor of choirs, including on Broadway, and as a composer and arranger of choral music. In 1985, when few foreign performers were appearing in China, he took a multi-racial choir to tour the country. Hairston was a founder of the Screen Actors Guild.

Also among the actors who appeared on Amos ‘n’ Andy was Roy Glenn, who had a rich baritone-bass voice that he got to use in one episode, singing some lines from “Red Sails in the Sunset.” Glenn had a long acting career, appearing in 96 films and television shows. His most prominent role probably was Sidney Poitier’s father in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967).

The only Amos ‘n’ Andy alumnus I’m aware of who not only is still living but has worked as an actor recently is Jay Brooks, who appeared in two episodes of Seinfeld, as Sid, the man who provides a service in Jerry Seinfeld’s neighborhood by moving cars from one side of the street to the other to comply with New York City’s alternate-side parking regulations.

The actors who appeared on Amos ‘n’ Andy were often criticized for accepting roles on a show that some people felt was demeaning to black people. More often than not, the roles offered to black performers in those days in any venue were stereotyped if they weren’t out-and-out offensive. Some of the actors — Alvin Childress, for example — argued that they had to work where they could and that by accepting parts on the first all-black show on television, they had paved the way for others to follow. It’s too late to resolve that question but, taken on its own merits, Amos ‘n’ Andy was a funny show, due in large part to the performances of a lot of experienced actors who, over their careers, made enormous contributions to American popular culture. They don’t deserve to be forgotten.

Books: “What a Wonderful World”

August 13, 2011

Sometime in the early 1960s, I went with a couple of my cousins to hear Louis Armstrong and his band play at Seton Hall University. I can’t remember how I decided to attend that show; there was not a single Armstrong recording among my LPs – which were dominated by operatic arias and country-and-western songs. I knew Armstrong from his television appearances, and I do recall finding him irresistible: not the trumpeter — I didn’t know from trumpets — the whole package. Whenever Armstrong’s image appeared on the black-and-white screen, I would pay attention. He was unique, and he was entertaining.

I was not aware until I read Ricky Riccardi’s recent book, What a Wonderful World, that the quality that attracted me to Louis Armstrong was the very thing that some folks found irritating, disappointing, even traitorous. Jazz purists objected to Armstrong’s departure from his musical roots in his native New Orleans, and many black Americans objected to his on-stage persona, in which they saw the perpetuation of the minstrel end man – a clown whose vocation was amusing white audiences. This was complicated by the fact that although Armstrong was at the height of his international fame in the heyday of the American civil rights movement, he played no visible part in the campaign — this, despite the fact that he and his band had often felt the sting of prejudice.

In fact, Armstrong refused for decades to appear in New Orleans as long as local laws prohibited mixed-race bands — perhaps an ironic position for him to take, given the fact that one of the raps on him was that he was willing to play before segregated audiences. His explanation was that he played where his manager booked him, and that he played for whoever wanted to hear him — and they were legion. Armstrong maintained that he contributed as much as anyone else to the progress of black Americans, because he paved the way for others to be received by white audiences.

His bookings are an interesting topic in Riccardi’s book. Armstrong’s manager during the last several decades of his career was Joe Glaser, a Chicago tough guy with a criminal background. There was some kind of bond between the two men — so much so that their arrangement was based on a handshake so that Glaser’s financial obligations to Armstrong were not spelled out. Glaser certainly got rich on the relationship, and Armstrong insisted that he had everything he wanted in life, including his daily regimen of marijuana and an herbal laxative that he treated as kind of a sacrament.

Riccardi describes in some detail the schedule kept by Armstrong and his band, the All Stars. It’s exhausting just to read about it. It was not unusual for the musicians to perform forty one-nighters in a row without a break — and this went on for decades. Outsiders thought Glaser was taking advantage of Armstrong, wringing out every dime he could before the man dropped dead. Armstrong denied this; Riccardi doesn’t seem to accept it, but even in the material the author provides in this book — such as a letter in which Armstrong complains to Glaser about being treated “like a baby” — there’s a strong insinuation that the critics were right. Armstrong himself insisted that he was doing what he wanted to do, but he also complained from time to time about exhaustion, and he lost more than one player from the All Stars because the grind was just too much.

Riccardi describes in some detail the schedule kept by Armstrong and his band, the All Stars. It’s exhausting just to read about it. It was not unusual for the musicians to perform forty one-nighters in a row without a break — and this went on for decades. Outsiders thought Glaser was taking advantage of Armstrong, wringing out every dime he could before the man dropped dead. Armstrong denied this; Riccardi doesn’t seem to accept it, but even in the material the author provides in this book — such as a letter in which Armstrong complains to Glaser about being treated “like a baby” — there’s a strong insinuation that the critics were right. Armstrong himself insisted that he was doing what he wanted to do, but he also complained from time to time about exhaustion, and he lost more than one player from the All Stars because the grind was just too much.

Riccardi, who is a student of music and an authority on Armstrong, defends Armstrong’s repertoire; the subtitle of the book is The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years. Among the criticisms of Armstrong was that he played almost the same song set night after night, to which Armstrong replied that he played what the paying audience expected him to play. As for the indictment of Armstrong’ s wide grin and rolling eyes, it never occurred to me that those mannerisms were supposed to be a stereotype of a black man — if it had occurred to me, I would have been offended and would not have been at that show at Seton Hall. To me, Armstrong was just being himself. Still, his position on race, as Riccardi presents it in this book, was ambiguous at most. At times he would lose his temper and rant about the way black Americans were treated, but he was also capable of making a statement in which he adopted a shaky rationale based on a distinction between “lazy” black people and industrious ones like him. In the event, Armstrong had almost no black audience when he was recording his enormous pop hits, “Hello, Dolly” and “What a Wonderful World” and whether that was due to his play list or to his attitude toward his race remains a matter of conjecture.

Riccardi, who is a student of music and an authority on Armstrong, defends Armstrong’s repertoire; the subtitle of the book is The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years. Among the criticisms of Armstrong was that he played almost the same song set night after night, to which Armstrong replied that he played what the paying audience expected him to play. As for the indictment of Armstrong’ s wide grin and rolling eyes, it never occurred to me that those mannerisms were supposed to be a stereotype of a black man — if it had occurred to me, I would have been offended and would not have been at that show at Seton Hall. To me, Armstrong was just being himself. Still, his position on race, as Riccardi presents it in this book, was ambiguous at most. At times he would lose his temper and rant about the way black Americans were treated, but he was also capable of making a statement in which he adopted a shaky rationale based on a distinction between “lazy” black people and industrious ones like him. In the event, Armstrong had almost no black audience when he was recording his enormous pop hits, “Hello, Dolly” and “What a Wonderful World” and whether that was due to his play list or to his attitude toward his race remains a matter of conjecture.

You can watch and listen to Armstrong sing and play “Mack the Knife” by clicking HERE.

“. . . brothers, sisters all ….” — Pete Seeger

November 23, 2009

As there isn’t enough turmoil in the land of my ancestors — well, some of them, anyway — a popular Lebanese singer has stirred the stew by including a derogatory reference to Nubian people in the lyric of a children’s song. I won’t go into what the lyric says, but it’s described in a story in the English-language newspaper in Beirut, and that story is right HERE.

Reading that story in the Daily Star sent me on a search for the Nubians, with whom I was not familiar. I found out that the term describes more than two million black people who are concentrated in southern Egypt and northern Sudan. They are one of our links to antiquity, because they have preserved culture and tradition that dates from the beginning of civilization.

Stumbling across the reference to these people and the information available about them reminded me of an experience we once had while flying to California. On the plane with us were a group of people in rural dress who had coal-black skin and who spoke to each other in a language we were sure we had never heard. When we surmised that one white man was with that party, we asked him about them, and he told us they were aboriginal artists from Australia who were on a world tour with an exhibition of their work. That encounter made us so conscious of how diverse the world is and how little we know about the many kinds of people who compose what we call humanity.

So, too, now with the Nubians. The Daily Star quoted a fellow named Motez Isaaq, who represents the Committee for Nubian Issues: “We are one of the oldest civilizations on Earth. Instead, our image is constantly perpetuated as the uneducated doorman or waiter.” Isaaq gave Wahbe the benefit of the doubt by saying her lyric was offensive even though she may not have intended it to be. And he added, according to the Star’s paraphrase, “that stereotypes of minorities are so entrenched that referring to them in popular culture media is frequently done unconsciously.” How sad and how discouraging, particularly since Wahbe, whether consciously or not, addressed her bias to children.