A gift horse of sorts

May 24, 2012

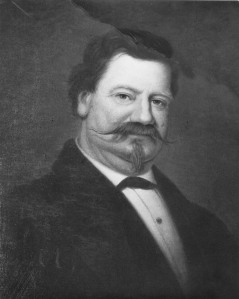

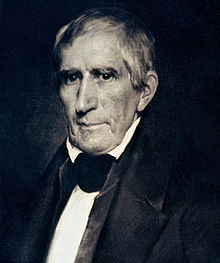

KING RAMA IV MONGKUT

When I discussed the book I wrote about in a post here this week, I got an unexpected response from several people who thought I couldn’t distinguish a camel from an elephant.

The book was “The Last Camel Charge” by Forrest B. Johnson, which reports on an experiment in which the U.S. Army imported several dozen camels from North Africa in the 1850s to see if they would perform better than horses and mules in the difficult conditions in the American Southwest. In about a half dozen cases in which I started to discuss this book, my companion asked me if I didn’t mean elephants. In all of these cases, they were mixing up the episode Johnson wrote about with the incident in which the King of Siam offered to send elephants to the United States for use as beasts of burden.

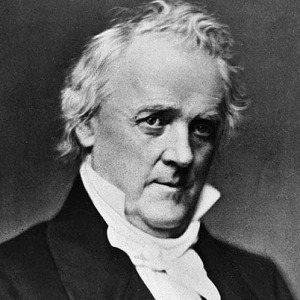

Most people who know about that offer heard about it in the musical play or the movie “The King and I,” in which, not surprisingly, it was badly distorted. In the movie and the musical, the King of Siam—Rama IV Mongkut—dictates, in English, a barely literate letter to Abraham Lincoln, offering to send the elephants. In reality, the king — who was fairly fluent in English — wrote such a letter, in his own hand, to Lincoln’s immediate predecessor, James Buchanan.

The king’s idea was that the elephants could be set free in the American wilderness and allowed to breed so that, as the herd grew, the animals could be captured and trained to carry cargo. Transportation being what it was in those days, that letter didn’t reach the White House until Buchanan had left office. So it was Lincoln who responded.

Lincoln, who signed the letter “your good friend,” wrote in part,

“I appreciate most highly Your Majesty’s tender of good offices in forwarding to this Government a stock from which a supply of elephants might be raised on our own soil. This Government would not hesitate to avail itself of so generous an offer if the object were one which could be made practically useful in the present condition of the United States.

“Our political jurisdiction, however, does not reach a latitude so low as to favor the multiplication of the elephant, and steam on land, as well as on water, has been our best and most efficient agent of transportation in internal commerce.”

From what I can tell, the portrayal of Mongkut in the stage show and the film was inaccurate in broader ways. While Yul Brynner, who created the role in both cases, represented the king as ignorant and in some ways boorish, Mongkut — a Buddhist monk and eventually an abbott — seems to have been well informed. He studied English, Latin, and astronomy and was an admirer of Jesus of Nazareth if not of Christian theological dogma.

Books: “The Last Camel Charge”

May 22, 2012

Samuel Bishop wanted to cross the Colorado River. Several hundred Mojave warriors objected. The factor that decided the argument: camels.

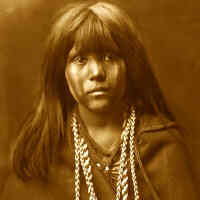

Forrest B. Johnson tells the story in his history “The Last Camel Charge.” It was April 1859, and Bishop’s friend and business partner — Edward “Ned” Beale — was leading a company of workers building a wagon trail between Arkansas and Los Angeles. The plan was for Bishop and a group of men from his ranch to rendezvous with Beale at the river and deliver supplies. But Bishop found his way blocked by Mojaves, whose people had lived in the region for a great many years. The Mojaves repelled Bishop’s first attempt to cross from California to the Arizona territory. After thinking things over, he hid the supplies, sent most of his men, wagons, and animals back to the ranch, leaving himself with 20 armed young men and 20 camels.

Camels? Six dozen of them had been imported from North Africa by the U.S. Army in an experiment championed by Jefferson Davis when he was a member of Congress and, during the administration of James Buchanan, secretary of war. The object was to determine if camels would be more serviceable than horses and mules in the punishing conditions in the American Southwest.

EDWARD BEALE

This experiment was carried on both by the Army and by civilians — namely Beale and Bishop. For the most part, it demonstrated exactly what its proponents expected. Camels could carry hundreds of pounds in excruciating heat without showing signs of fatigue. They would eat mesquite and cactus and almost any other vegetation that crossed their paths, whereas mules and horses required some form of grass. And, of course, camels could go for days without drinking, whereas desert travelers relying on horses and mules were frequently obliged to leave the trail and search for water to keep the animals alive.

Bishop had borrowed the camels from the Army. Now, although he was leading a troupe of civilians, he put them to military use. As he approached the river, he found an estimated 500 Mojave assembled there to deny him a crossing. He assembled his men, mounted on camels in four rows of five each. They galloped — likely at 40 miles per hour — directly into, and through, the ranks of the Mojave. Bishop crossed the river and didn’t lose a man.

In spite of all the evidence that camels were more suited than other animals to travel in the deserts of the Southwest, the experiment didn’t last very long after Bishop’s charge. There was a complex of reasons for that, not the least of which was the outbreak of the Civil War in 1860. Among other effects of the war was the departure of Jefferson Davis, camel proponent par excellence, from the federal government. Davis, of course, took up the secession cause and became president of the Confederacy.

In spite of the title of this book, camels aren’t the only subject Johnson covers.

The writer places the camels in the wild milieu that was the American West in those days. For example, he reports extensively on the conflict between the Mormons who had migrated to the Utah Territory to escape from the turmoil they had become embroiled in further east. When they were settling in Utah, they wanted to live on their own terms, and that brought them into conflict with the national government. At one point, while the Beale expeditions and the camel experiment were going on, President Buchanan, perhaps hoping to distract attention from the growing crisis over expansion of slavery into the western territories, declared the Mormons in rebellion against the United States and ordered the Army to deal with them— something, fortunately, that became unnecessary.

The writer also gives vivid accounts of the rigors encountered by folks traveling across country — the weather, the terrain, the hostile and violent people, not all of them natives.

Books: “A Natural Woman”

April 27, 2012

It may not be possible to dislike Carole King.

It may not be possible to dislike Carole King.

What’s not to like? She has written some of the best pop and rock songs of the past five decades, she has a record of social responsibility, and she’s a nice person.

In a way, her memoir, A Natural Woman, is similar: What’s not to like? It’s a conversational account of a remarkable American life; in some ways, it would be hard to believe if one didn’t already know that it’s true. King (Carol Klein) is a Brooklyn native who found herself in awkward straits in school because her mother enrolled her early, and then she skipped a grade — so she was perennially younger than her classmates and felt out of place.

She showed early signs of a bent for entertaining, and she was writing songs in her teens. In fact, she was only 18 when she and her husband, Gerry Goffin, wrote “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” for the Shirelles. She also became a mother for the first of four times at around the same time. Among the songs she has written since then, either on her own or with a collaborator, are “Where You Lead, I Will follow”; “I’m Into Something Good”; “It’s Too Late, Baby”; “The Loco-Motion”; “Take Good Care of My Baby”; “Go Away, Little Girl”; “I Feel the Earth Move;” “You’ve Got a Friend,” and “Natural Woman.’’

For a long time, King saw herself as a writer and “sideman” — that is, one of the musicians playing and even singing behind a lead performer. By King’s account, James Taylor changed that single-handedly. It occurred in 1970 while Taylor was touring to promote his album “Sweet Baby James.” King was to play piano for Taylor at a performance at Queens College, which was her alma mater. As the show was about to begin, Taylor told King he wanted her to sing lead that night on “Up on the Roof,” a song she had written with Goffin and a favorite of Taylor’s (and mine, not that it matters).

King writes that she was taken aback by this request but had no time to talk Taylor out of it. When that spot in the set came around, Taylor introduced King to the audience as an alumna of the college and a co-writer of the song and, without rehearsal, she took her first turn as a lead singer. In time, of course, she become a good enough lead that her album Tapestry become one of the best selling collections of all time.

King devotes a lot of space in this book to a personal life that is difficult for an outsider to fully understand. She married Goffin when she was 17, and the pair, barely more than children, settled into suburban life in West Orange. But Gerry got restless, he fooled around with drugs, he eventually plunged into serious depression. The marriage ended, but King and Goffin continued to be friends and collaborators. King had three more marriages, none of which, based on her own accounts, seem to have been well thought out. Two ended in divorce and one ended when her husband — who she says struck her on several occasions — died as a result of a drug overdose.

King emphasizes in this book that she didn’t like touring and that she didn’t seek stardom because of the baggage that came with it. She had a yen for a simple life, particularly as compared to life in the New York City and Los Angeles areas. From both a cultural and environmental point of view, she carried that quest to its logical extreme by buying a ranch in Idaho. Before she picked the spot, in fact, she and her fourth husband, Rick Sorensen, and her two youngest children lived for three years in a cabin that had no electricity, running water, or heat.

When King first decided to make Idaho her principal residence, her oldest child, Louise, then 17, declined to make the move, and she stayed behind in Los Angeles. Eventually, all of King’s children would wind up in California. All of those children apparently have had fruitful lives, but King’s priorities are still a little hard to grasp.

When King first decided to make Idaho her principal residence, her oldest child, Louise, then 17, declined to make the move, and she stayed behind in Los Angeles. Eventually, all of King’s children would wind up in California. All of those children apparently have had fruitful lives, but King’s priorities are still a little hard to grasp.

I found it disconcerting, too, that she devoted a chapter to her decision to practice yoga, remarking that the discipline helped her find her “center.” She presents this as a life-shaping event, but she never explains what she means by finding her center, and except for one glancing reference, she never mentions yoga again.

Perhaps because she is such a nice person, King chooses her words carefully when she’s describing her interactions with other people, even the husband who brutalized her. While it wouldn’t necessarily be useful for her to share any rancor she might be harboring, her approach is tentative enough to make a reader wonder what else she chose to withhold.

King mentions an editor in the acknowledgments, but I was happy to find that it seemed as if this book was largely King’s own work. It has the feel of a kitchen-table conversation. Apparently it is as much as King wanted to share, so it will have to do for now.

Books: “Nixon’s Darkest Secrets”

March 30, 2012

There is a scene in a PBS documentary about Jack Paar that illustrates as well as anything why William Shakespeare would have loved Richard Nixon.

The scene comes from a 1963 episode of Paar’s groundbreaking talk show. Nixon, since leaving the vice presidency, had lost elections for president and for governor of California, but for a two-time loser, he was in a good mood — one might say light-hearted, a term not often associated with RMN.

Paar reminds the audience of something that was widely known at the time, namely that Nixon was a piano player. Paar also explained, to Nixon’s obvious amusement, that Nixon had also written some music for the piano and that his wife had made recordings of him playing his own tunes.

Paar said that bandleader Jose Meles had used one of those recordings to write an arrangement to back up one of Nixon’s compositions, and Paar asked Nixon to take to the keyboard.

Before complying, Nixon noted that Paar had asked earlier about Nixon’s political ambition. “If last November didn’t finish it, this will,” Nixon said, “because — believe me — the Republicans don’t want another piano player in the White House,” a reference to Harry S. Truman whose musical virtuosity was about on the same level as Nixon’s.

When I saw this incident on a PBS documentary about Paar, I thought about what a complex creature a human being is, and I thought about that again when I read Don Fulsom’s book, Nixon’s Darkest Secrets. Considering the depth and breadth of Nixon’s corruption and paranoia, I wouldn’t have thought it possible for a writer to do a hatchet job on the old trickster, but Don Fulsom has managed it.

On paper, at least, Fulsom has some credentials to be writing about this subject. He covered the White House and was Washington bureau chief for United Press International, which once upon a time was a viable news agency. Having been a journalist myself for more than 40 years, I would have expected a writer with Fulsom’s resumé, producing a book this long after Nixon’s death, to provide some insight into the whole man. As deeply immersed in muck as he was, after all, Nixon didn’t spend his whole time drinking himself blotto, assaulting people who annoyed him, beating his wife, raking in dough through his bag men, or plotting to have people like Jack Anderson killed.

On paper, at least, Fulsom has some credentials to be writing about this subject. He covered the White House and was Washington bureau chief for United Press International, which once upon a time was a viable news agency. Having been a journalist myself for more than 40 years, I would have expected a writer with Fulsom’s resumé, producing a book this long after Nixon’s death, to provide some insight into the whole man. As deeply immersed in muck as he was, after all, Nixon didn’t spend his whole time drinking himself blotto, assaulting people who annoyed him, beating his wife, raking in dough through his bag men, or plotting to have people like Jack Anderson killed.

And while his administration was forever besmirched by his prolongation of the Vietnam war and his order for the secret and murderous bombing of Cambodia, it was productive in many ways, including creation of the Occupational and Health Safety Administration , the National Endowment on the Arts, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Nixon approved the first significant step toward a federal affirmative action program. And Nixon — as probably only he could have — altered the course of modern history by changing the U.S. relationship with the Soviet Union and China.

Although Fulsom has riffled through some of the more recently released documents about Nixon, he hasn’t contributed anything to our understanding by recounting in nauseating detail the depravities of the man’s life. We get it. He was a sleaze. But he was also this other guy. This guy with a remarkable grasp of foreign affairs. This guy who supported a lot of moderate initiatives. And this guy who played the piano. And from this distance, that’s what’s so fascinating about him.

Look for Fulsom’s book with the scandal rags at the checkout counter. Shakespeare would have told the whole story.

You can see Nixon playing the piano on Jack Paar’s show by clicking HERE.

Books: “Eisenhower: The White House Years”

March 25, 2012

When I was a grad student at Penn State, former President Dwight Eisenhower visited the campus. It wasn’t a public event; he was speaking to a group of students from State College High School. But I was working in the public information office and found out about it and simply walked into Waring Hall at the appointed time. It was 1964 — a different era. Nobody asked who I was.

When I was a grad student at Penn State, former President Dwight Eisenhower visited the campus. It wasn’t a public event; he was speaking to a group of students from State College High School. But I was working in the public information office and found out about it and simply walked into Waring Hall at the appointed time. It was 1964 — a different era. Nobody asked who I was.

Eisenhower had been out of office for about four years. He was 74 and had suffered heart attacks and a stroke. Still, he stood at the edge of the stage with his head high and his shoulders back — in short, with the military bearing long associated with him. He encouraged those kids to take an interest in civic affairs and not to expect other folks to do all the work either inside or outside of government.

Eisenhower had been an iconic figure in our house, both because of his role in World War II and because he had kept the presidency out of Democratic hands for eight years.

Some of the family’s faith in Ike was well placed, even given the straight party-line mentality, but of course he was more complicated than he was portrayed around our place.

And, in fact, the Dwight Eisenhower that Jim Newton describes in Eisenhower: The White House Years is a complicated guy. While he was still in office, especially during his second term, he was often lampooned as an absentee president who golfed while the Soviets and Chinese plotted to conquer the world.

While it’s true that Eisenhower tried to fit golf and bridge into his routine, that characterization seemed ludicrous at the time, and Newton demonstrates well that it was fantasy. He shows that, on balance, Eisenhower’s administration, which kept the United States out of a shooting war for eight years, launched the interstate highway system and the St. Lawrence Seaway, and left the country with its last budget surplus until 1999, was an overall success.

Newton doesn’t discuss this in detail in this book, but Eisenhower’s achievements as supreme allied commander in Europe during World War II were in a significant way due to his firm but understated command as well as his personal diplomacy as he coordinated military officers and heads of state who had little or nothing in common except an enemy.

Similar qualities came into play when Eisenhower took on the presidency. He wasn’t inclined to the grand gesture, and his credo was what he called “the middle way,” meaning that on any issue he looked for the ground that was equidistant from extremes on either right or left.

Meanwhile, while Ike might have seemed like a man obsessed with cutting down on his slice, he was engaging in intense discussions concerning the rising belligerence of the Soviets and Chinese, more than once talking his military brass out of resorting to nuclear weapons. He was also overseeing covert activities undertaken by the CIA to overthrow foreign governments whose behavior was perceived as inimical to American interests — Iran and Guatemala among them. Eisenhower also made flight-by-flight decisions about high altitude surveillance of the USSR, and his administration was embarrassed when one of the planes was shot down and the pilot captured.

From our perspective, two of the most disappointing things about Eisenhower were his unwillingness to take the lead on civil rights for black citizens and his public silence about the demagoguery of Sen. Joseph McCarthy.

Eisenhower was content with the concept of “separate but equal,” and he was unhappy with the Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs the Board of Education. When the Board of Education in Little Rock, Arkansas, decided to obey the spirit of that ruling by admitting nine black teenagers to Central High School, there was immediately a crisis of authority as Gov. Orval Faubus, the Arkansas National Guard, and a howling white mob prevented the kids from entering. Eisenhower tried to finesse the problem by summoning Faubus to Washington and bargaining with him, but Faubus double-crossed Ike by withdrawing both the National Guard and himself from the scene. So Eisenhower was forced to do something distasteful to him, sending members of the 101st Airborne Division, with bayonets fixed, to escort the students into the school.

Eisenhower was content with the concept of “separate but equal,” and he was unhappy with the Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs the Board of Education. When the Board of Education in Little Rock, Arkansas, decided to obey the spirit of that ruling by admitting nine black teenagers to Central High School, there was immediately a crisis of authority as Gov. Orval Faubus, the Arkansas National Guard, and a howling white mob prevented the kids from entering. Eisenhower tried to finesse the problem by summoning Faubus to Washington and bargaining with him, but Faubus double-crossed Ike by withdrawing both the National Guard and himself from the scene. So Eisenhower was forced to do something distasteful to him, sending members of the 101st Airborne Division, with bayonets fixed, to escort the students into the school.

Eisenhower didn’t say or do anything publicly about McCarthy’s paranoid campaign of terror against real and imagined communists until the senator overreached and directed his venom at the U.S. Army. Then the president issued an order forbidding employees of the executive department from providing evidence to McCarthy’s committee.

Eisenhower’s reticence concerning McCarthy extended to the point that Ike let McCarthy pillory Gen. George Marshall, Ike’s mentor and possibly the man he most admired. Eisenhower ostensibly regretted that for the rest of his life, but the damage had been done.

Eisenhower’s reticence concerning McCarthy extended to the point that Ike let McCarthy pillory Gen. George Marshall, Ike’s mentor and possibly the man he most admired. Eisenhower ostensibly regretted that for the rest of his life, but the damage had been done.

Newton probably is a little easy on Eisenhower, but if he is, he’s easy on a man who led one of the most unselfish and productive lives of public service in American history, a life untouched by the personal and professional corruption and the blind partisanship that has affected major figures in American history before and after him.

The motto of Eisenhower’s election campaign — “I like Ike” — was particularly apt. He had his flaws as we all do, but the quality of his public service flowed to a large extent from his character: He was a nice man.

Books: “The Nazi Séance”

February 27, 2012

One of the most bizarre characters among the opportunists, lackeys, and hangers-on who orbited around Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party was Erik Jan Hanussen — a mentalist who is the subject of Arthur J. Magda’s book The Nazi Séance.

Hanussen, who worked his way up from rinky-dink vaudevillian to international celebrity, lived on the edge. Driven almost entirely by his appetite for fame and fortune, he dazzled some people and irritated others, and while he was being applauded for his feats on stage he was also being hounded by skeptics and enemies.

His act consisted of such effects as finding people in an audience whose names had been written on slips of paper and sealed in envelopes, finding hidden articles, telling strangers details about their lives, and occasionally foretelling the future.

Hanussen also conducted private consultations and séances for which he charged substantial sums.

Hanussen also conducted private consultations and séances for which he charged substantial sums.

He had many critics, but the most serious challenge to his credibility may have been a criminal case of fraud brought against him in Czechoslovakia. Although he probably had defrauded the people involved, he beat the charges after the judge, who seems to have been sympathetic anyway, allowed Hanussen to conduct a daring demonstration of his skills in the courtroom.

He also became a target of the communists who in the late ’20s and early ’30s were struggling with the Nazis for political control of Germany and who had no patience with such things as magic and spiritualism.

Some of the Nazis, on the other hand, including some high-ranking ones, were caught up in a post-World War I wave of interest in other-worldly things.

Hanussen, Magida writes, had no interest in politics or government, but he cast his lot with the Nazis to the extent that he used his charisma and manipulative skills to make some influential friends, not the least of whom was Count Wolf-Heinrich von Helldorf, head of the Nazi storm troopers in Berlin. Hanussen, who lived lavishly, entertained Helldorf in style and, while the Nazis were still trying to consolidate their power, the mentalist repeatedly lent money to Helldorf, holding onto the IOUs. Hanussen, who owned a newspaper in Berlin, used it to vigorously promote Adolf Hitler and his party.

Hanussen’s success was to a large extent a result of his hubris, and the primary example of that was the fact that he was not a Danish aristocrat, as he claimed, but an Austrian Jew named Hermann Steinschneider.

How he kept this from the Nazis for as long as he did is unclear, particularly since he continued to observe some Jewish rituals. In fact, one of his three wives converted to Judaism when she married him.

Eventually he was outed, first by a German communist newspaper and then by a Nazi publication. Even after this happened, he continued to behave with an extraordinary recklessness. He went too far, though, in February 1933, when he conducted a séance attended by some Nazi elite and tried to goad a hypnotized young actress into talking about a large fire. The following day, the Reichstag, seat of the German government, was torched. The circumstances surrounding that fire are still in dispute, but the Nazis blamed the communists. Magida writes that Hanussen, from his apartment, inexplicably telephoned the editor of a communist newspaper — a man he was otherwise unlikely to talk to — to inform him of the fire and warn him of the possible consequences.

In addition, Hanussen tried to use Helldorf’s IOUs to strong-arm the Nazis into letting him in on a lucrative business deal from which he had been shut out. The Nazis hadn’t been in power very long before three men took Hanussen for a ride. His body, with three shots in it, was found much later in the forest where he had been killed.

Unlike most of the Nazis’ millions of victims, Hanussen asked for it. Ironically, the success he enjoyed before he was eliminated was in part a result of an attitude that he shared with Hitler, who took advantage of the desperation and aimlessness of the German people after the combined blows of defeat in World War I and deprivation during the Great Depression. The following remarks are Hanussen’s, but they might have come from either man:

“”Their sadness comes from the fact that they don’t have a teacher, a father, a boss, a friend who impresses them enough that they can trust him. Why do these people come to me? Because I am stronger than they are, more audacious, more energetic. Because I have the stronger will. Because they are children and I am a man.”

Books: “A Slave in the White House”

February 21, 2012

Folks confer a couple of lofty titles on James Madison, but “hypocrite” isn’t usually one of them. But Elizabeth Dowling Taylor isn’t bashful about using that term in her book A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons.

The subject of the book was born into slavery on Montpelier, Madison’s farm in Virginia, and remained in bondage until he was 46 years of age. Within the stifling confines of slavery, Jennings rose to the highest possible place, serving for many years — including the White House years — as Madison’s “body servant.” That meant that he attended to Madison’s personal needs — shaving him, for instance — and traveled with him pretty much everywhere. He also was often the first person a visitor encountered, and he supervised the other household staff in preparing dinners and receptions. Taylor surmises that Jennings, who was literate, paid a lot of attention to the conversations that took place when political and social leaders visited the Madisons.

One of the influential people Jennings became familiar with was Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, who served as a U.S. senator and as secretary of state. Madison had agreed, under pressure from a family member, to provide in his will that his slaves would be freed after specified periods. Madison — whose titles included “Father of the Bill of Rights” — reneged on that commitment and left about 100 slaves to his wife, with the provision that they would not be sold and that they would be freed at some point. When Dolley Madison began selling slaves in order to allay her financial problems, Jennings approached Webster, who had in the past assisted slaves. Webster arranged through a third party for Jennings to buy his freedom; Jennings worked for Webster for several years, and eventually, Webster took on the loan himself.

Jennings was the father of five; he married three times and was widowed twice. When he had satisfied his debt to Webster, he took a job in the Interior Department and worked there until a few years before his death in 1874. During the balance of his working life, he was a bookbinder.

Jennings also seems to have been something of an activist. The evidence Taylor had at her disposal suggested to her that even while he himself was a slave, he forged documents for others trying to get to free states and that after he had achieved his own freedom he was a player in the largest known attempt by slaves to escape to the North — 77 men, women, and children who tried to slip out of Washington via the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay.

The most dramatic incident that occurred during Jennings’ years as a slave probably was the invasion of Washington by British troops in 1814. By Taylor’s account, Jennings was one of the servants at the White House with Dolley Madison when the alarm came that the house had to be evacuated, and he evidently was among the small group that removed the life-sized Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington that now hangs in the East Room. The painting almost certainly would have been destroyed when the British ransacked and burned the mansion.

Taylor’s account of Jennings’ life provides a lot of insight into slavery in Virginia, which was a complex system governed by both necessity and tradition. Her book also explores the contradictory position in which Madison and his close friend, Thomas Jefferson, found themselves. Both men publicly acknowledged that human slavery was essentially evil and that it should be eliminated, but both men kept scores of slaves to labor on their behalf. They were openly berated for this by abolitionists in the United States and by visitors from abroad. The Marquis de Lafayette, for example, visited the United States in 1824 and told Madison and Jefferson that he was nonplussed to find that almost a half century after he had fought for human liberty in the colonies, two of the principal figures of the Revolution were still keeping human beings in bondage.

Madison gave what turned out to be only lip service to emancipation, insisting that while it was desirable, it was also more important to preserve the federal union. Madison also argued that any plan to emancipate slaves had to include a plan to remove them from the United States — probably to west Africa, where none of them had ever lived. His reasoning was that black and white Americans could not live together in peace, and he based that conclusion on his opinion that black people were a depraved race, lazy, profligate, and likely to resort to violence — an idea that apparently was not diluted by his long and close exposure to Paul Jennings, who was none of those things.

Books: “Masters of Mystery: The Strange Friendship of Arthur Conan Doyle & Harry Houdini”

February 13, 2012

While I was a grad student at Penn State, a family magic act appeared at Waring Hall. The show must have been either cheap or free, because we were living on $77 a month, and we went. With us was Michael Moran, an actor, who was visiting us that week. After each trick, Michael explained how it was done. All but one – the one in which the father in this family act crumpled up a piece of paper into a ball, placed it on a tennis racket, held the racket out at a right angle to his body, bouncing that wad of paper until it turned into an egg. He took the egg off the racket and broke it into a glass bowl. Michael couldn’t explain that one.

Intellectually, I knew that the magician had pulled a switch, but somewhere in my being I wanted to believe that he had changed that ball of paper into an egg.

This was nothing new. When I was a kid, I religiously (sic) watched Joseph Dunninger’s TV show. Dunninger was a mentalist who performed astounding feats and and made a standing offer of a $1,000 reward — a lot of money then — for anyone who could show that his subjects were in kahoots with him. Still, he ended every show by saying something like the following: “And remember, a child of ten could do the things I do, after thirty years of practice.” I found that disclaimer disappointing; I would rather he had said nothing and left us guessing — and left me able to believe that he could read minds.

I imagine that same neurotic desire in audiences contributed a lot to the success of Harry Houdini, and also the success of spiritualists and mediums who claim they can summon the spirits of the dead. Those folks are the subject of Christopher Sandford’s book, Masters of Mystery: The Strange Friendship of Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini.

The title is a little misleading in that Houdini and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes stories among other things, were never really “friends.” It was more that they were interested in each other, almost obsessed with each other. What they were interested in was their contrary opinions about contacting the dead. Doyle got immersed in that subject because of his own bereavements, and he was convinced not only that intelligence could exist apart from the body but that the dead could communicate with the living, notably through mediums, and that he himself had experienced it. He seriously believed that a new religion should be established based on that premise. Houdini, on the other hand — who had bereavement issues of his own — didn’t discount the possibility of life after death or even the concept of communicating with the dead, but he made a second profession out of investigating mediums and concluded that all of them, including Conan Doyle’s wife, were frauds.

The two men did correspond and then meet, and they exchanged visits with their families, but there was never any prospect that one would convert the other. Such friendship as there was came to an end when Conan Doyle’s wife, Jean, conducted a seance in which she purported to contact Houdini’s deceased mother, repeating the mother’s messages to her son through “automatic writing,” meaning that Jean’s hand involuntarily scribbled down what Cecilia Weiss was saying. Conan Doyle was convinced; Houdini was not, inasmuch as Jean wrote in English, a language Mrs. Weiss had never spoken, and called her son by the wrong first name. Houdini was polite about it at the time, but he later denounced the seance as a fake.

Although Conan Doyle was subjected to some criticism, he conducted a vigorous campaign to promote the ideas of spiritualism, drawing big crowds wherever he went. Houdini, on the other hand, took a lot of trouble to expose individual mediums as phonies, driving some of them out of the business. Sandford alludes several times to the obvious irony that Conan Doyle, who had invented the relentlessly logical Holmes, could accept as legitimate supposedly spiritual events for which there was no support or which were debunked by calmer minds. As for Houdini, it’s impossible to know how much of his crusade was based on his professed outrage over the manipulation of people who were desperate to contact their lost loved ones and how much was driven by the showman’s instinct that had made him an international celebrity.

Books: “William Henry Harrison”

January 27, 2012

United States presidents and baseball players have at least this in common: They can alter the record books just by showing up.

United States presidents and baseball players have at least this in common: They can alter the record books just by showing up.

A case in point is William Henry Harrison, the ninth president and the subject of a book by the same name — one of the Times Books series of short biographies of the presidents. The author is New York Times columnist Gail Collins.

Harrison was in office hardly a month, but he still made his marks. He was the first presidential candidate to personally campaign for the office. He was the last president born before the Declaration of Independence. He gave the longest inaugural address. He was the first president to be photographed while in office. He was the first president to die in office. He was the first president to die in office of natural causes. He served the shortest term — 31 days. He was part of one of two sets of three presidents who served in the same year — 1841 and 1881. He was the only president whose grandson was president.

As Gail Collins recounts with a lot of good humor, the campaign of 1840, in which the Whig Harrison defeated the incumbent Democrat Martin Van Buren, was a first of its kind, too, in the sense that it was the first really populist election in the United States, the first one that wasn’t dominated by a political and economic elite.

As Gail Collins recounts with a lot of good humor, the campaign of 1840, in which the Whig Harrison defeated the incumbent Democrat Martin Van Buren, was a first of its kind, too, in the sense that it was the first really populist election in the United States, the first one that wasn’t dominated by a political and economic elite.

Harrison had unsuccessfully challenged Van Buren in 1836 when the fractious Whigs ran two candidates — basically a northern and a southern. But in 1840, the party got behind Harrison and he far out paced Van Buren in electoral votes, although the popular vote was much closer. More than 80 percent of the eligible voters participated — a statistic that must be filtered through the fact that women and a great many men did not have the franchise in those days.

As Collins describes it, the Whig campaign was like a three-ring circus, with literally thousands of stump speakers going from town to town, parades, rallies, and dinners with plenty of alcohol.

The campaign was further distinguished by the Whigs’ successful effort to sell the public a candidate whom they could appreciate — a kind of frontiersman, one of the common folks, whose idea of a good time was flopping down in his log cabin and swilling hard cider.

In actual fact, Harrison was born on a Virginia plantation, was well educated and very mannerly, drank only in moderation and disapproved of drunkenness, and lived in a 16-room farmhouse in Ohio.

The 21st century voter may not be surprised to hear that the facts didn’t matter. The public bought the lie, which was encouraged with all kinds of “log cabin” events, images, songs, and verses, and other Whig politicians were happy to let some of the backwoods shading rub off on them.

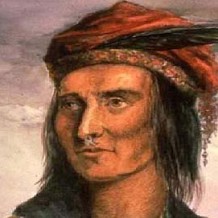

This was also the campaign of “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” — the “Tyler” being a reference to vice-presidential candidate John Tyler. Harrison had served in the army before retiring to his farm, and he was involved in several fights with the Indians and British in the struggle over the Northwest Territories. In one of those battles, near the juncture of the Tippecanoe and Wabash rivers in the Indiana Territory, Harrison, who was governor of the territory, routed a settlement being built by the brothers and Shawnee leaders Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (“the Prophet). Harrison had far more men, and he took far more casualties, and the battle wasn’t really decisive in the long run. He had a couple of much greater successes under his military belt. But, hey, “Tippecanoe and Tyler too” rhymes, and the alliteration was irresistible.

It is well known that Harrison was inaugurated on a bitter winter day, and that he foolishly appeared at the outdoor event — including his two-hour speech — without a hat or coat. Gail Collins explains further that the amiable president-elect arrived in Washington already exhausted from both celebratory events and sieges by office-seekers, and that the pressure didn’t let up in the capital.

The author writes that Harrison was 67 years old when he campaigned for the office, and that the Democrats dismissed him as a feeble old man — not a far-fetched idea in 1840, when a man of that age frequently was in his dotage. Collins says Harrison’s recklessness might have been his attempt to refute the Democrats’ claims. In any case, shortly after the inauguration, he came down with what was probably pneumonia. He died on April 4, 1841.

Books: “A Soldier’s Sketchbook”

January 13, 2012

During World War II, the popular radio star Kate Smith used to end her daily broadcasts by saying, “And remember … if you don’t write, you’re wrong!” Kate Smith, who was a major supporter of the war effort in general and of American troops in particular, was prodding those at home to send letters to soldiers and sailors. I don’t know whether Kate Smith introduced that expression, and that inspired a songwriter, or the other way around. I do know that a writer named Olive Kriser wrote a song by that title in 1943, and it, too, urged families and friends to write to the troops.

For me, that phrase has always evoked what I imagine was a melancholy aspect of the war years: young men and women suddenly separated from their families, friends, neighbors, familiar surroundings, everyday routines, and hurled into the maelstrom, wondering about the folks, about ever seeing them again, longing for a mundane conversation around the kitchen table, a cheese sandwich made by Mom. And yearning, yearning, for a word from home.

That was the real-life experience of tens of thousands of young people, including Joseph Farris of Danbury, Connecticut, who was drafted, trained, and shipped off to the fighting fields of France and Germany shortly after leaving high school.

Farris, who has become a very successful cartoonist and illustrator, has recreated his experience in A Soldier’s Sketchbook, an elegant volume published by National Geographic. Farris got lots of letters, but in this book, he reproduces many of the letters that he wrote to his parents and two brothers during the three years, beginning in May 1943, that he spent in the United States Army. The book also contains facsimiles of some of those letters and of other documents, photographs of Farris and some of his colleagues, and watercolors and drawings that he did while he was in service.

Farris, who has become a very successful cartoonist and illustrator, has recreated his experience in A Soldier’s Sketchbook, an elegant volume published by National Geographic. Farris got lots of letters, but in this book, he reproduces many of the letters that he wrote to his parents and two brothers during the three years, beginning in May 1943, that he spent in the United States Army. The book also contains facsimiles of some of those letters and of other documents, photographs of Farris and some of his colleagues, and watercolors and drawings that he did while he was in service.

Farris provides a narrative in which he demonstrates how he pulled his punches in his letters home, both because military censorship sharply restricted what combatants could write about and because he didn’t want to worry his family. The folks wouldn’t know until it was well over that Farris — who wound up heading a heavy machine-gun platoon — came under heavy fire, watched his fellows soldiers being blown away, shivered in the cold and wet of the foxhole, and confronted the fact that any hour could the last in his brief life.

By the time Farris got into combat, Italy had surrendered, Athens had been liberated, France had been invaded, and the German siege of Leningrad had been broken. The jig was up for the Third Reich. So although he experienced the worst of the war, he also had some less lethal duty, moving through towns in France and Germany and temporarily occupying houses that were far more comfortable than a hole in the ground.

By the time Farris got into combat, Italy had surrendered, Athens had been liberated, France had been invaded, and the German siege of Leningrad had been broken. The jig was up for the Third Reich. So although he experienced the worst of the war, he also had some less lethal duty, moving through towns in France and Germany and temporarily occupying houses that were far more comfortable than a hole in the ground.

A touching aspect of this book is the writer’s lack of self pity and his consistent concern for the well being of his parents and brothers. While he was still in harm’s way, he wrote to his younger brother George, “Dad, Mom, & I are exceedingly grateful, kid, that you are around to help out. Mom & Dad depend a helluva lot on you, so don’t let them down. You may work a little harder than many other fellows your age but in the long run it’s going to pay. You don’t know how thankful I am for the training I got in the store” — a reference to his family’s Danbury Confectionery — “not only the business experience but the systematic method necessary. You’re fortunate in having the swellest folks possible. If I can treat my future children half as good as Mom & Dad have treated us I’ll feel that (I) have done my job well.”

Throughout his military service, Farris thought about his plans for a career in art, and often asked his family to send him supplies. His work has appeared in the New Yorker and in other major publications. You can see many of his cartoons and illustrations by clicking HERE.

For another interesting aspect of World War II, click HERE to read about the Women’s Land Army. The site includes many letters written home by Genevieve Wolfe, who was one of a group of 40 young women from West Virginia who traveled to a camp in Ohio to provide labor needed on farms in the northern part of the state.