Amazon Update No. 6: “The Other Sister”

November 20, 2014

Movies that accurately portray the lives of people who have mental disabilities are important. Such movies, by helping the general population better understand the exceptional people in their midst, can create a healthier and more constructive environment for everyone. The Other Sister,’ a 1999 film starring Diane Keaton and directed by Gary Marshall, tried to do that but fell on its face. In fact, it was embarrassing for me to watch, and it should have been embarrassing for the actors to perform.

The “other” sister of the title is Carla Tate, played by Juliette Lewis, who is mentally challenged in some way but who is bright and personable and eager to live independently. Carla is the youngest of three daughters of well-off parents, Elizabeth and Radley, played by Diane Keaton and Tom Skerritt.

At the beginning of the film, Carla has successfully completed the course of study at a private boarding school and is returning to her family’s home. She wants to get on with her life (and by that she means get training at a public polytech school, get a job, and get an apartment), but Elizabeth has no confidence in her daughter’s ability to do anything but live under the protection of her parents. Radley — who seems to have licked a drinking problem — is a little more willing to let Carla stretch. Carla does go to a tech school, and there she meets Danny McMann (Giovanni Ribisi) who, of course, is also mentally challenged and, it seems, less bright and emotionally stable than Carla. The two strike up a friendship and then fall in love and then become sexually active — an aspect of their story that the filmmakers handled with exquisite clumsiness. Carla wears Elizabeth down enough to get an apartment, but Danny isn’t doing as well in school, and his absentee father cuts off funding for any further education. There is a painful scene in which Danny attends a country club Christmas party with Carla and her parents, is intimidated by the surroundings, gets hopelessly drunk, grabs the bandstand microphone and blurts out his feelings for Carla and the fact that the two have been having sex. She is furious at the crowd for laughing at her, as she interprets their reaction, and at Danny for embarrassing her. The next we see of Danny, he is on a train heading home, wherever that is.

Cut to the wedding ceremony of the second of the three daughters. Marshall, perhaps to demonstrate that the spirit of Laverne and Shirley is never quite exorcized from his soul, brings Danny back, in the balcony of the church, of course, from whence he interrupts the nuptials with a parody of The Graduate. The young couple, now reunited, want to wed, but Elizabeth won’t consent. Carla and Danny are determined to marry with or without Elizabeth’s blessing or presence, but the worth reader can no doubt anticipate how that turns out. As if to test how much an audience can tolerate in a 139-minute movie, Marshall and the other writers arrange for Danny, who was a kind of gofer for the polytech’s marching band, surprise Carla outside the church with the band in full regalia marching by and playing “Seventy-six Trombones.”

I guess the filmmakers were concerned that this movie would not seem socially relevant, and so they included a subplot in which Elizabeth is estranged from her third daughter, who lives in a gay relationship. Guess what happens at the end.

The most annoying thing about this movie is that it treats a serious subject like a sit-com. The annoyance is aggravated by the patronizing portrayals of both of the young people—although Juliette Lewis does her best with what she was given to work with—and by the improbable and even slapstick scenes. Marshall doesn’t seem to know what he wants to do with those characters, or maybe he’s simply not competent to deal with such personalities. How else to explain that on one hand Carla is presented to us as mature, confident, and determined, while on the other hand she accompanies her mother to a benefit event at an animal shelter and starts barking at the dogs being housed there and ultimately turns them loose. The sequence in which a bartender at a high-end country club serves an obviously troubled young man one powerful drink after another stretches credibility to the breaking point. A scene in which Elizabeth comandeers a golf cart to chase a distraught Carla across the country club lawns is hopelessly absurd. And Keaton’s portrayal of the inconsistently up-tight Elizabeth can set one’s teeth on edge.

Roger Ebert, of happy memory, commenting about this film, cited Jean-Luc Godard’s observation that the best response to a bad film is to make a good film. In this case, Ebert wrote and I agree, that film is Dominick and Eugene. Don’t see this one; see that one.

Amazon Update No. 5: “The Holiday”

November 12, 2014

I met Shelley Berman in 1972. He was staying in Bernardsville, New Jersey — I think it was Mike Ellis’s house — and appearing in a production of Neil Simon’s Last of the Red Hot Lovers at the Paper Mill Playhouse in Millburn. Berman had become widely known because of his television appearances. His signature routine was sitting on a stool and talking on an imaginary telephone — a bit he put his stamp on before Bob Newhart used it in his own act. I had always thought of Berman as a kind of reiteration of Oscar Levant. I never met Levant, but Berman’s often dour persona reminded me of what I had read about the pianist-composer. I also think that certain points in their lives, they resembled each other physically. I found Berman to be articulate. I remember quite well the case he made about the damage critics can do to performers’ careers. It was something he had experienced himself and had thought a lot about; he could have made that argument before a jury.

I bring up Shelley Berman because we saw him the other night in a 2006 movie, The Holiday. I watch movie credits right to the end, and that’s how I discovered that Berman was in the movie. He had a small role, and I hadn’t recognized him. He was 82 years old when he made that film. But when I saw his name in the credits, I went back into the movie to have a look. I wouldn’t have known him, but the point is that he was a perfect choice for the part he played. And that — the casting — is what makes this movie worthwhile.

The Holiday, which was produced and directed by Nancy Meyers, is about two women who are unhappy in love. Iris Simpkins (Kate Winslet), who writes a society column for The Daily Telegraph of London, has been in love with a colleague for years. He is an affectionate and manipulative friend; he’s also engaged, and there is no prospect for him to return her passion. Meanwhile, frenetic Amanda Woods (Cameron Diaz), who owns and operates a lucrative Los Angeles company that makes movie trailers, finds out that her live-in lover has been having an affair with his secretary. Both women abruptly decide to take a holiday to assuage their anguish and, under the only-in-the-movies rule, they end up swapping houses. The outcome is exactly what you’d expect — in a movie.

But although the plot is obvious and implausible, the casting decisions were impeccable and the result is a very entertaining movie. Winslet and Diaz are perfect as the ingenuous Iris and the frantic Amanda. Jude Law is disarming in an unusual role for him; he plays Iris’s brother, Graham,who makes Amanda’s visit to England worthwhile. Eli Wallach, who was 90 years old when this film was shot, has a tour de force as Arthur Abbott, a retired screen writer with whom Iris develops a warm relationship that revs up the lives of both parties. Shelley Berman plays a buddy of Abbott. The most ingenious stroke of all was the choice of Jack Black as Miles, a sympathetic Hollywood composer who shares with Iris a weakness for the wrong lovers. The script was written with Winslet, Diaz, Law, and Black in mind. Any one of us could had written it, as far as the story line goes, and the reviewers had a few things to say about that, but the movie with its stable of charming characters still made money.

Dustin Hoffman has a brief uncredited cameo in this film. It occurs when Miles and Iris go to a video store and are discussing The Graduate. Hoffman appears as a customer who overhears their conversation and reacts with a whimsical smile. Hoffman has said that he noticed all the cameras and lights at a Blockbuster store and stopped to find out what was going on. He ran into Meyers, whom he knew, and she wrote him into the scene.

Shelley Berman performed one of his telephone routines on Judy Garland’s television show. It is introduced by Garland and a short musical number. To see it, click HERE.

“That Trixie’s a sweet kid” — Ralph Kramden

November 6, 2014

When Joyce Randolph marked her 90th birthday recently, I took a glance at the Wikipedia article about her to see how recently it had been updated. Among the things I read there was that she was recruited to play Trixie Norton in Jackie Gleason’s series The Honeymooners after Gleason saw her doing a commercial for Clorets, which was a chlorophyl gum on the order of Chicklets. That isn’t what she told me when I visited her at her Central Park West apartment in 1976. On that occasion, she said that she had first been hired by Gleason to appear in a serious sketch he insisted on performing on his comedy-variety show, The Cavalcade of Stars, which was then being broadcast on the Dumont Network, originating at WABD, Channel 5, in New York.

“Gleason liked to write for the show or suggest things to the writers,” Joyce told me. “This time he wanted to do a serious sketch about a down-in-the-heels vaudevillian who meets a woman he loved many years before. We did very little rehearsing, and when we went on with it people were a little flabbergasted. They didn’t know whether to laugh or cry or what. A couple of weeks later, the part of Trixie came up, and Gleason said, ‘Get me that serious actress.’ ” Perhaps the Clorets commercial got her cast in the dramatic turn, but however Joyce got cast as Trixie Norton, she became an immortal among television actors. The Honeymooners first appeared in October 1951 as a six-minute sketch on The Cavalcade of Stars. The sketch became one of the regular features on the show; Trixie Norton was introduced as a former burlesque dancer and was played, in only one episode, by Elaine Stritch before Joyce Randolph got the part. In later and less successful iterations of The Honeymooners Trixie was played by Jane Kean, but the part is universally associated with Joyce Randolph.

That is true, in part, because Joyce played the part when The Honeymooners was broadcast as a free-standing half-hour sitcom in 1955 and 1956. Those thirty-nine episodes are among the most revered examples of American television comedy. While many shows from that era — Our Miss Brooks and The Life of Riley, for instance — seem stilted in retrospect, The Honeymooners still entertains viewers who have seen the episodes over and over again. Joyce didn’t claim to know definitely why that should be so, but she speculated that one factor was the spontaneity of the performances. “We filmed a show once, and we did it with an audience,” she told me. “We’d start at 8 o’clock and we’d be finished by 8:30, just as though we did it live.” She said the cast would rehearse on Monday and Tuesday and film a show on Wednesday, then rehearse on Wednesday and Thursday and film a show on Friday.” Gleason himself frequently skipped rehearsals and missed cues and confused the lines during the filming, but there were no breaks or re-takes, so those mistakes were preserved as part of the shows. Joyce Randolph told me that in those early days of television, some audience members became so absorbed in the show that they lost their sense of what was real and what was not. “In fact,” she said, “people used to send in draperies and tablecloths for the set; they thought the Kramdens really lived like that.”

Joyce Randolph was kind of the Zeppo Marx in the Honeymooners act, because her own personality was not that distinctive (perhaps making her a perfect choice to play the wife of a New York City sewer worker) and she was playing fourth fiddle to three strong character actors — Gleason, Art Carney, and Audrey Meadows. Still, her own genuine earnest and wholesome quality came through in Trixie’s persona, which is why no one really could replace her in that part.

Amazon Update No. 4: “A Walk in the Spring Rain”

October 15, 2014

Ingrid Bergman and Anthony Quinn should have quit while they were behind. These two giants of the screen appeared together in the 1964 film The Visit, and it was a disaster. We didn’t know that before we watched their next joint venture, A Walk in the Spring Rain, released in 1970. This film, based on a novel by the same name by Rachel Maddux, has the disadvantage of never making sense.

Bergman plays Libby Meredith, a New York City woman whose husband, Roger (Fritz Weaver) is a college professor. Roger is under pressure to publish an academic work, so he takes a sabbatical, and the couple repair to a rented house in rural Tennessee where Roger plans to hold forth on some aspect of the Constitution of the United States. This move occurs while the Merediths are in the midst of a disagreement with their married daughter, Ellen (Katharine Crawford), who wants to attend law school but isn’t getting either encouragement or any offer of material assistance from her parents. The film doesn’t help us understand the couple’s chilly response to their daughter’s ambition. The rental house is overseen by a local man, Will Cade (Quinn), who immediately takes a shine to Libby and makes no attempt to hide it. He pursues her right under Roger’s nose until she succumbs. The problem is that it is not clear why she succumbs. We had the feeling that we were supposed to think she was bored with a husband who was absorbed in his academic career, but Roger is portrayed in the film as being attentive and even playful with her.

It also strains belief that Libby and Will carry on this affair while Roger is not only unaware of it but happily lets his wife go off on jaunts with this earthy guy who is always leering at her and making suggestive remarks. Not everyone is as blind as Roger, though, and the relationship between Libby and Will eventually explodes in lethal violence. Even after that, the pair are able to keep their liaison a secret from Roger. In movies and plays about infidelity, I like to have some sympathy for the transgressors, and that’s usually because I have no sympathy for the offended partner. But this story gives me no reason to dislike Roger or even Will’s eccentric spouse, Ann, played by Virginia Gregg. On the other hand, Quinn doesn’t come across as attractive or endearing — although I think director Guy Green was going for that — but rather as a predator who has no regard for anything but his own desires.

This movie was filmed in Tennessee and it’s premiere was held in Knoxville. Ingrid Bergman sat next to Rachel Maddux during the screening. The TCM web site quotes from Bergman’s autobiography her account of this event: “(A)ll through the film she was saying to me, ‘What is this?…What happened to the scene when she?…This isn’t meant to be here…this is later…Haven’t they understood that?’ …I didn’t know what I could do to help her. The book had been so well written, full of the country and the true feelings of a woman in this situation…and now poor Rachel Maddux had seen her book go down the drain. So she went to the ladies’ room and cried. I went after her and tried to comfort her…The film had been a good try. We’d started off with such high hopes. I thought maybe we could do a film with that elusive feeling which Brief Encounter [1945] had. We’d worked hard. We’d done our best and at the end of it we’d made Rachel Maddux cry.”

Books: “The Romanov Sisters”

September 14, 2014

It’s a shame that William Shakespeare didn’t live long enough to know the Romanovs. They would have made a great subject for one of his tragedies. I think of that every time I read about them, and the idea was reinforced by Helen Rappaport’s recent book, The Romanov Sisters. The title refers to the daughters of Nicholas II and Alexandra, the last emperor and empress of Russia. The girls — Olga, Maria, Tatiana, and Alexandra — their brother Alexei, their parents, and several retainers, were murdered by Bolshevik thugs in Siberia in 1918. Rappaport has written about that, but in this absorbing book she focuses on the years from the births of the five children to their deaths. Although the sisters are supposed to be the principal subjects of this book, Rappaport really provides a portrait of the whole family. And her portrait gives the impression, which I have drawn from other books on this subject, that these Romanovs were nice people who were unsuited for their position in life. One example of the character of these people is that Nicholas and Alexandra, unlike most royal couples in that era, married for love and remained deeply in love for the rest of their lives.

NICHOLAS and his children, OLGA, TATIANA, MARIA, ANASTASIA, and ALEXEI in a photograph taken by the empress Alexandra.

One of their overriding obligations was to produce a male heir for Nicholas, but the first four children were girls. One after another, these births sent reverberations throughout Russia where the question of an heir became a preoccupation the moment Nicholas succeeded to the throne. Although they were aware of the implications, Nicholas and Alexandra reveled in the arrival of each of their daughters. When the heir, Alexei, finally did arrive, the euphoria within the family was muted when he was diagnosed with hemophilia — the royal disease. Helping her son became an obsession for Alexandra. In itself that was natural and maybe even commendable, but it exacerbated existing problems with Alexandra’s public image. Among the Russians, she was suspect from the start, because her background was not Russian but English and German. She was a favored granddaughter of Victoria. She frustrated both common and privileged Russians, too, by living an insular life, preferring to hunker down with her immediate family rather than appear in public, even at state occasions where her presence would have been expected.

The Russian gossip circuits, and diplomatic circles, buzzed over the plain, almost homespun manner in which the four grand duchesses dressed, their casual demeanor among the few outsiders they spent time with — notably the sailors and officers on the royal yacht — and the infrequency of the girls’ public appearances. Alexandra’s isolation was a result both of her choice of a lifestyle and of her multitude of real and imagined illnesses, and it was aggravated by her exhausting focus on Alexei’s condition. Her tendency to keep her children close by deprived them of a full social life to the extent that the ostensibly future emperor of all the Russias would frequently shrink from strangers who visited the family’s home. Alexandra’s standing among the Russians, including the royal family, wasn’t improved any by her association with Grigori Rasputin, the enigmatic, unkempt “holy man” who, it seemed to the empress, was the only person capable of easing her son’s suffering. Rappaport is not judgmental in writing about Rasputin, and she provides what for me was new context by including input from Rasputin’s daughter. I also learned from Rappaport that it was not only Alexandra but also her daughters who felt a strong emotional and spiritual attachment to the strange man.

Russians suspected Alexandra’s loyalty because of her apparent aloofness and her British and German origins. And yet one of the most dramatic aspects of her life occurred during World War I when she and her two older daughters took formal training as nurses and worked in hospitals, some of which they themselves established. By Rappaport’s account, this was no publicity stunt, but a serious undertaking, often in gruesome circumstances, including the many amputations performed on soldiers carried back from the front.

Nicholas and Alexandra were complicit in their own undoing because of their firm belief in a divinely sanctioned monarchy, their stubborn adherence to a lifestyle that did not meet the expectations of either their subjects or the international community, and their failure in general to read the signs of the times. Still, it’s difficult to come away from their story without a deep sense of sadness over the waste of what might have been beautiful lives.

“Surrounded by assassins!”

August 28, 2014

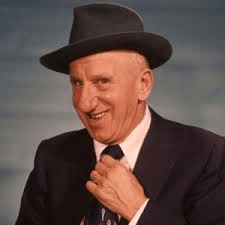

Two crossword puzzles that I recently completed had clues that referred to Jimmy Durante. In one, the solution was Durante’s surname; in the other, the solution was his nickname, “Schnozzola.” Designers of crossword puzzles seem to assume — accurately, for all I know — that theirs is an aged audience. But for the annual rebroadcast of Frosty the Snowman, few people today would ever hear Durante’s voice. My guess is that few people under forty years of age know who he was. This is a natural consequence of the passage of time and of changing tastes in entertainment. Durante was a talented jazz pianist, comedian, and all-around showman. He also set a standard for humility, decency, and generosity. He probably was one of the most recognizable stars of his time, and his “time” lasted for fifty years.

Two crossword puzzles that I recently completed had clues that referred to Jimmy Durante. In one, the solution was Durante’s surname; in the other, the solution was his nickname, “Schnozzola.” Designers of crossword puzzles seem to assume — accurately, for all I know — that theirs is an aged audience. But for the annual rebroadcast of Frosty the Snowman, few people today would ever hear Durante’s voice. My guess is that few people under forty years of age know who he was. This is a natural consequence of the passage of time and of changing tastes in entertainment. Durante was a talented jazz pianist, comedian, and all-around showman. He also set a standard for humility, decency, and generosity. He probably was one of the most recognizable stars of his time, and his “time” lasted for fifty years.

I wonder how many people who see the 1992 film Scent of a Woman catch the reference to Durante. In that film, retired and blind army Lt. Col. Frank Slade, who is bent on suicide, is forced off the ledge, as it were, in a violent struggle with a prep school student named Charles Sims. When the climactic scene winds down, the exhausted Slade, played by Al Pacino, mumbles in a hoarse voice, “Did you ever have the feeling that you wanted to go, but still have the feeling that you wanted to stay?” Even before that line was appropriated for Pacino’s Oscar-winning role, it had been appropriated to express profound ideas about life and death — and particularly about the transition from one to the other. But it didn’t start out that way. Far from originating in deep thought, the line was written and made famous by the antithesis of deep thought, Jimmy Durante. It’s on the order of Groucho Marx’s trademark tune, “Hello, I must be going.” Durante sang the lyric as early as 1931 in a long-forgotten movie, The New Adventures of Get Rich Quick Wallingford. He sang it to Monty Wooley in the 1942 film version of The Man Who Came to Dinner. And he sang it again in the 1944 film Two Girls and a Sailor. In that case, as on many other occasions in his long career, he used it as an introduction to another of his compositions, “Who will be with you when I’m far away?”

To see Pacino deliver the line and Durante sing it to Monte Wooley, click HERE.

To see Durante’s performance in Two Girls and a Sailor, click HERE.

Robin Williams

August 12, 2014

The genius of Robin Williams first sunk in for me when we saw him in the motion picture Awakenings in which he played a character based on the neurologist Oliver Sacks.

We didn’t see that film principally because Robin Williams starred in it but because we were interested in the topic. Sacks pioneered the use of the drug L-Dopa by treating a group of patients who had been in a catatonic state for decades as a result of an epidemic of encephalitis that lasted from 1917 to 1928. But we were impressed by Williams’ portrayal which was very understated. And it was only later, when we saw an earlier documentary with the same title, that we realized how well the often manic Williams had captured the shyness of Dr. Sacks.

The breadth of his range was one of the wonderful things about Robin Williams. Recently, we happened to watch again the hilarious but poignant movie Bird Cage in which he co-starred with Nathan Lane. In spite of the over-the-top humor laced through that movie, Williams’ character was restrained, and the contrast with Lane’s flamboyant character is an important reason why the film works so well.

Pat and I had a chance to chat with Robin Williams in 1998 at a party following the New York premiere of the movie Patch Adams, in which Williams played the unorthodox doctor who wanted to use humor in the treatment of patients. At the invitation of our friend Marvin Minoff, who co-produced that film, we attended the premiere at the Ziegfeld Theater and then the party at Four Seasons. We noticed Williams standing alone, so we approached him, intending only to compliment him on his performance, but he seemed willing to talk, so we willingly obliged. The conversation was so casual that I can’t recall details, except that he spoke of his mother, describing her as his first audience. He was subdued, but Pat and I agreed afterward that he was remarkably accessible for a person of his stature and that he seemed to be pleasant to the core, which, in its way, is as precious a quality as any other.

In one of those coincidences that one wouldn’t dare hope for, we finished our conversation with Robin Williams and spied Dr. Oliver Sacks, apparently trying to hide among the leaves of a rubber tree plant. I had read all of the books he had published up to that point, so we moved on to what turned out to be another conversation for another post.

One of Robin Williams’ foils in Patch Adams was played by Phillip Seymour Hoffman, who also struggled with internal demons and died tragically. You can view both actors in a scene from that film by clicking HERE.

Books: “The Presidents’ War”

August 5, 2014

When President Martin Van Buren died, 19 of his successors had already been born. At the onset of the Civil War, four of them — John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan — joined Van Buren in that exclusive category, former presidents. That was the only time five former presidents were living at one time until 1993 when Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush were still kicking around. It happened again in 2001 with Carter, Ford, Reagan, Bush, and Bill Clinton. The quintet that formed a sort of elite gallery watching the Union unravel are usually ranked in the bottom dozen or so when retrospective experts, who never faced such decisions, cast their ballots. But none of the former presidents saw themselves that way and, in that rough-and-tumble time, they didn’t pose as aloof elder statesmen while Abraham Lincoln dealt with the crisis of secession. What they did do is the subject of The Presidents’ War by Chris DeRose.

This is an unusual and possibly unique approach to the history of the three decades leading up to the war and the prosecution of the war itself. The Civil War is sometimes remembered simplistically as a war over slavery — either over whether slavery should be permitted in new states as the nation expanded westward or whether it should be abolished altogether. Both of these questions were at issue, but the controversy was more complicated than that because it was intertwined with the evolving understanding of the relationship between the states and what was then often referred to as the “general government” — the federal government. The rights of individual states vis-a-vis the federal government are still the subject of often contentious discourse, but the question was far less settled in the decades before and immediately after the Civil War than it is now.

Differing views over that question led to a crisis in 1832 when South Carolina declared that tariffs imposed by the federal government that year and in 1828 were null and void. Andrew Jackson, a tough customer, was president at the time, and he ordered that the duties be collected by whatever means were necessary and he formally declared that states did not have the power to nullify federal regulations or leave the federal union. The crisis was put off, in a sense, by a political compromise; it was put off, but not settled, and it would simmer and occasionally come to a boil until it exploded in secession and war. After Jackson, eight men, beginning with Van Buren, would exercise the executive authority while these fundamental questions remained unresolved and repeatedly threatened to rupture the union. Two of them — William Henry Harrison, the ninth president, and Zachary Taylor, the twelfth president, would die in office and would not play a significant role in government, and one of them, James Knox Polk, the 11th president, would die shortly after leaving office in 1849. Those five who would live to see the nation descend into the bloodiest war in its history had differing points of view on the seminal questions of the time. Although they are usually overlooked or derided in accounts of this period, DeRose explains in detail how they all were engaged in promoting their positions and often were active participants in the political dynamics of the time.

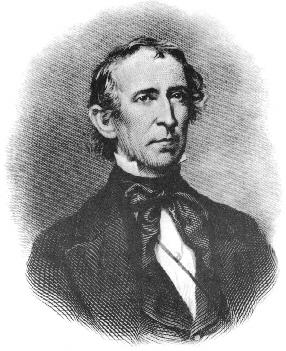

Perhaps the most interesting character DeRose brings back into the light is John Tyler of Virginia, the first man to serve as president without being elected to the office (succeeding Harrison, who died after a month in the White House) and the only former president to become a sworn enemy of the United States. During the administration of James Buchanan, Tyler acted as a go-between seeking an accommodation between the United States and the newly formed Confederacy. Tyler promoted and chaired a ill-fated peace convention in 1861 and then participated in the convention in which Virginia voted to secede from the Union. Tyler was eventually elected to the Confederate Congress, although he died before he took his seat. Although the circumstances were dubious, this last achievement made him one of only four former presidents to serve in public office, the others being John Quincy Adams, Andrew Johnson, and William Howard Taft.

Martin Van Buren of New York, who served one term as president, had ambitions to return to the White House, but they were ultimately frustrated. He was one of many Americans who held that slavery was morally wrong but that it was protected by the Constitution. Although he was initially opposed to the election of Abraham Lincoln, Van Buren ultimately supported him and the war effort. Millard Fillmore, also of New York, was the last Whig president and, therefore, the last president who was not associated with either the Democratic or Republican parties. When the crisis had reached the point of no return and Lincoln called on the northern states to raise troops, Van Buren supported him, as did Fillmore. Van Buren argued that “the attack upon our flag and the capture of Fort Sumter by the secessionists could be regarded in no other light than as the commencement of a treasonable attempt to overthrow the Federal Government by military force. ….”

Fillmore was elected vice president on the ticket with Zachary Taylor and was vaulted into the presidency by Taylor’s death. He, too, skated on the thin ice between his own professed abhorrence of slavery and both the fact that it was protected by the Constitution and his desire to avoid antagonizing the southern states. He was sufficiently repulsed by slavery, in fact, that he raised money and contributed some of his own to enable his coachman to buy his own freedom and that of his family, but Fillmore supported enforcement of the fugitive slave law because it was the law of the land and because, like his four contemporaries, he did not want to provoke the South into Civil War. Three years after he left office, he unsuccessfully ran for president on the ticket of the anti-Catholic American Party, although he himself was not anti-Catholic. Although he was opposed to secession, he did not support Lincoln’s decision to emancipate slaves as a means of expediting an end to the war.

Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire, who was a brigadier general during the war with Mexico, was a Democrat who was opposed to secession but openly supported the institution of slavery in the South. He was a close associate of Jefferson Davis, who became president of the Confederacy, and antagonistic toward Lincoln. Pierce, who was beset by personal tragedy and drinking problems, attempted to undermine Lincoln’s policies by organizing an unprecedented “commission” of the living former presidents to mediate the differences between North and South. The commission, which would have been heavily weighted against Lincoln’s positions, never materialized.

James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, Lincoln’s immediate predecessor, had adopted the problematic view that states did not have a right to secede from the union and that the federal government did not have the power to stop them by force.

Buchanan, who had had a distinguished career, particularly as a diplomat, failed to preserve the peace between North and South and left office stinging with the idea that he would be regarded as a failure as president. It wasn’t known at the time, but he had exerted pressure on the Supreme Court to broaden its pending ruling in the Dredd Scott case to not only determine Scott’s status but to state that Congress did not have the power to prohibit slavery in the western territories. He spent his retirement years at his home in Wheatland, but he persistently trumpeted the idea that his policies were precursors to Lincoln’s. Buchanan busied himself during that time writing a memoir in hopes of vindicating himself, but he is generally regarded as having been hopelessly inept, at least with regard to secession.

DeRose covers a lot of ground in this book, but by telling the story in terms of the presidents who tried to cope with nagging and explosive issues, he brings as clarity to the subject that is not always present in accounts of that complex period. And besides writing a history of the run-up to the war, he provides a chronicle of the evolution of a public office — the presidency — noting that the five former presidents who lived to see secession and war had “feared that he would break the customs of the office that they had established and carefully cultivated. Their concerns were well founded. The American presidency is now a dynamic institution and powerful force for principle in the hands of the proper occupant…. Often American has been bereft of the leadership it wanted. But … in hours of great crisis for the Republic, America has never failed to find the reader to match the moment.”

“This call to the bullpen is brought to you by . . . .”

July 25, 2014

My brother often shares with me his irritation with the broadcasters who describe Yankee baseball games on television and radio. We were, after all, raised in baseball by Mel Allen and Red Barber, in whose care baseball play-by-play was an art. In a way, no announcers can satisfy us with Mel and Red as a standard. This week, my brother complained that John Sterling, who does the radio broadcasts with Suzyn Waldman, has repeatedly called attention to the fact that the 1927 Yankees used only 25 players over the whole season. I guess that was an implied criticism of, or at least a contrast to, the multiple roster changes — making trades, buying contracts, and bringing kids up from the minors — the Yankees have made during this season in which, incidentally, eighty percent of the starting rotation is on the disabled list.

In fact, however, making comparisons between baseball in the 1920s and baseball in the 2000s is a tricky business. Sterling was right about the number of players on the Yankees’ roster in ’27, and my cursory tour through the statistics for that season suggest that 25 was a low number even then. But Sterling didn’t pick the ’27 Yankees at random. He picked that team because that team won 110 games and rolled over the Pirates in four games in the World Series. He picked that team because that team is often identified as the greatest team ever. That’s an indefensible ranking because — very much to my point here — baseball was so much different before that era and has become so much different since.

But certainly the 1927 Yankees were one of the greatest teams ever, and that was due in large part to the presence of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Earl Combs, and Tony Lazzeri. The major league season in 1927 was 154 games. Because of a game that ended in a tie, the Yankees that year played 155 games, and those four players each appeared in more than 150. Gehrig played in 155. So there was a significant element of stability built into the roster. I don’t know if this has been analyzed scientifically, but I often hear it said that players then were less injury prone and less likely to sit down because of an injury. Gehrig carried this last propensity to extremes, which helped to account for his appearing in every Yankee lineup for fourteen years.

The Yankees that year also had five starting pitchers who among them won 82 games. The ace, Waite Hoyt, who won 27 games, threw a total of 256 innings. And in those days before specialization, Wilcy Moore, a reliever, pitched a total of 213 innings and won 19 games. So the rest of the pitching staff had to account for only nine wins. Moore threw 213 innings in 1927. What with the modern system of middle relievers, set-up men, and closers, the most innings a Yankee reliever threw last season was 77.