The bigger they are . . . .

March 16, 2010

Once again the other morning, instead of getting up I clicked on the TV and turned to Turner Classic Movies. Never a good idea. We ended up watching “The Harder They Fall,” a 1956 movie starring Humphrey Bogart, Rod Steiger, and Virginia Mayo. It was Bogart’s last film; he died the following year.

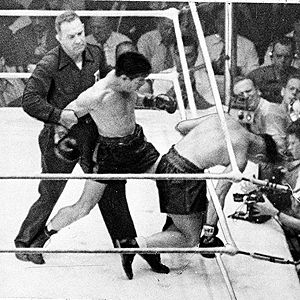

“The Harder They Fall” was ostensibly based on the life of Primo Carnera, and if it was, it wasn’t meant as a compliment to the Italian boxer. The film concerns an Argentine giant who is brought to the United States by an unscrupulous promoter (Steiger) whose angle is to build up the unwitting and incapable kid through a series of fixed bouts and then bet against him when he fights for the heavyweight title. As far as I know there is no proof, but there is a persistent story Carnera was used in just that way.

The cast of “The Harder They Fall” included Jersey Joe Walcott, who won the world heavyweight title in 1951, when he was 37 years old. Walcott — who served as sheriff of Camden County and chairman of the N.J. State Athletic Commission — played a trainer in “The Harder They Fall,” and seemed comfortable in the part.

Also in this cast was Max Baer, who played the heavyweight champion who beat the Argentine kid and put an end to his career. This appears to have been a none-to-subtle reference to the fact that Baer took the title from the 275-pound Carnera in 1934. There is also an episode in this film in which the boxer played by Baer gives his opponent such a beating that the man suffers brain damage and dies. That, too, happened in Baer’s career: In 1930, a fighter named Frankie Campbell — brother of Dodger star Dolph Camilli — died after a bout with Max Baer in San Francisco.

Max Baer — father and namesake of the actor-director-producer who played Jethro in “The Beverly Hillbillies” — appeared in a couple of dozen movies and television productions. His brother, Buddy Baer — who was just as hard a puncher — had a record of 52 wins and 7 losses with 46 knockouts. He never won a title, but he had the distinction of once knocking Joe Louis out of the ring — in a fight that Louis ended up winning on a disqualification call. Baer claimed Louis had hit him and knocked him down after the bell ended the seventh round, and he refused to answer the bell for the eighth. Buddy Baer, too, appeared in numerous movies and television shows after he gave up boxing.

There were other personable guys who dabbled in entertainment after they were through in the ring, including Rocky Graziano and “Slapsie” Maxie Rosenbloom.

Graziano was a New York street brawler and thief who did time on Riker’s Island and spent lots of time in other sorts of incarceration and under the protection of the Catholic Church. He went AWOL from the Army after punching an officer, and he was suspended from boxing for failing to report an attempted bribe and again for running out on a bout. He was a very good boxer and immortalized himself in the annals of the sport for his three bloody fights with Tony Zale in 1946, 1947, and 1948. The second of those fights made Graziano middleweight champion of the world.

After his fighting career, Graziano — who, like a lot of guys with his background, was a charismatic figure — became a popular entertainer, especially on television comedies and variety shows.

Rosenbloom won the world light heavyweight title in 1932 and held it until 1934. On the one hand, his method of moving around the ring made it hard for opponents to land decisive blows, but that quality also meant that his fights often went the distance, and he took a lot of shots to the head. This eventually affected his physical health. Still, he capitalized on the image of a goofy pug and became a familiar figure on television. Although he wasn’t a serious actor, he played a significant role in Rod Serling’s “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” the iconic boxing story that starred Jack Palance and Ed and Keenan Wynn and included in its cast Max Baer.

In an interesting parallel, Primo Carnera, who was even more unlikely an actor than Rosenbloom, also hit one high note in a limited screen career. Carnera was a giant. When he defended his heavyweight title against Paolino Uzcudun, the two fighters weighed a total of 488 3/4 pounds — the most weight ever in a title match. And when he defended the title against Tommy Laughran, the average weight of the two fighters was 227 pounds, but Laughran weighed only 184. It was the biggest disparity ever in a title bout.

Carnera used his size and generally menacing appearance to his advantage in the 1955 film “A Kid for Two Farthings,” and he won critical approval for his portrayal of villainous wrestler Python Macklin.

The news that Chan Ho Park has signed to pitch for the Yankees got me to thinking about men from other countries who have played in the Bigs. Players from the Spanish-speaking Americas and from the Caribbean have been around the majors for a long time, but the signing of Park shows that there are still frontiers to be crossed: He is the first big-league player to have been born in South Korea — or in any Korea, for that matter.

The first player from outside the United States was probably Andy Leonard, who was a native of County Cavin, Ireland. Leonard broke in in 1876 as a second baseman and left fielder with the Boston Red Caps and appeared with that team until 1878. In 1880 he played shortstop and third base with the original Cincinnati Red Stockings.

Although Leonard was born on the Auld Sod, he was raised in Newark, N.J., and got some of his early playing experience with a club in Irvington. In ’76, when he broke into the majors, five other players from Ireland appeared with major league teams, along with five from England and one from Germany, which means that England and Ireland had more representatives in the big leagues than all but four states of the Union — New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New Jersey.

Other than the United States, the Dominican Republic has contributed the most players to the Major Leagues — 494 through the 2009 season. Venezuela is second with 246 and Canada is third with 225. Puerto Rico, which is part of the United States, has chipped in with 228.

Considering all the Italian-Americans who have played Major League baseball — not the least of whom were the three DiMaggio brothers — it’s curious to find that there have been only six players who were born in Italy. The first of these was Lou Polli, who was born in Baveno, which is up there in the Piedmont region. Polli pitched a few innings of relief for the St. Louis Browns in 1932 and didn’t appear again until 1944 — a war year in which a lot of guys who otherwise wouldn’t have been in baseball got a crack at it while the regulars were Over There. In ’44, Polli pitched almost 36 innings for the Giants.

The most successful Italian-born player was Reno Bertoia, who might as well have been a Canadian inasmuch as his family moved there when Reno was a year old. He was born in St. Vito al Tagliamento in the comune of Udine, which is near the border of Slovenia. He played in the big leagues from 1953 to 1962, the first six and last two of those years with the Tigers. He was an infielder — a second and third baseman — and he had a lifetime batting average of .244 over 612 games. After he retired from baseball, he was a Catholic-school teacher for 30 years in Windsor.

The Baseball Almanac has a lot of stats about foreign-born baseball players at THIS LINK.

“Half the lies they tell about me ain’t true” — Yogi Berra

February 21, 2010

I’m ready to talk baseball, not that I ever stop. The camps are up and running, Johnny Damon has signed with the Tigers, George Steinbrenner was out watching his grandson play in a high school game, and the Yankees are starting to say “Chamberlain” and “bullpen” in the same sentence with more and more consistency.

The more things stay the same, they more they stay the same, and Yogi Berra turned out for yet another spring training. It seems to me that there is a doctoral dissertation in Yogi Berra, maybe in American Studies. Some scholar should examine the history of Berra’s public image, which is more like Babe Ruth’s image than is immediately apparent. The man hasn’t been a day-to-day part of baseball for decades, and his name is still known to people who know nothing about the game, who weren’t yet born when Berra played his last game or, for that matter, managed his last game. He has ears like flapjacks and a hound-dog mug that now looks like a relief map of northern Greece. And we love him.

It is a little early for serious talk about the 2010 season, what with Joe Girardi saying things like this: “I think our No. 1 concern is ironing out our lineup. When I say it’s a concern, I’m not concerned that we don’t have the players to do it, I’m concerned with where you place them.” Uh, did he read that in one of Casey Stengel’s old notebooks?

In my search for some baseball intelligence, the most interesting thing I found today was about a game played in 1953. Several sites have picked up on this story, originally published in the New York Times. This is a hilarious account of Whitey Ford and Mickey Mantle arguing about how the Yankees aborted an 18-game winning streak by losing a game to the St. Looie Browns. As the writer demonstrated, both players were sure of themselves and both had it very very wrong. It’s an object lesson for the rest of us when we’re cock sure of our memories. You can read it by clicking HERE.

It’s been a good reading season squeezed in between semesters. The pace will slow down when classes resume next week, though I just started a fascinating book about Isaac Newton’s little-known career as the scourge of counterfeiters. Of that, more later.

I just finished “The Girls of Room 28” by Hannelore Brenner, which describes the lives of children who were incarcerated at the Jewish ghetto in Theresienstadt, Czechoslovakia, between 1941 and 1944. An estimated 13,000 children passed through there; 25 survived. Some died of disease or other consequences of neglect. Most died in the concentration camps further east. Brenner presents first-hand accounts from some of the survivors as well as material from diaries and other such documents. She also records how the Nazis bamboozled the International Red Cross into thinking that Theresienstadt was a model community for Jews, founded on the benevolent nature of Adolf Hitler. There is a lot of information and photographs about the ghetto on the YAD VASHEM web site.

I can’t read too many books about Abraham Lincoln, and I was delighted with “Lincoln, Life-Size,” a volume that includes digitized reproductions of all 114 known photographs of Lincoln, most of them portraits. The book was assembled by three descendants of Frederick Meserve, one of the best-known collectors of Lincoln images. The authors used high technology to calculate the size of Lincoln’s head. The head was cropped from each of several dozen photographs and reproduced on the facing page in life size. The result is fascinating and, at times, unsettling. The authors also accompany each photograph with texts drawn from a variety of sources, some putting the photo in context, others illuminating some aspect of Lincoln’s public or private life.

“America’s Girl” is a biography of Gertrude Ederle, a young woman from New York City who, in 1926, not only became the first woman to swim the English Channel, but far surpassed the previous record — set, obviously, by a man. Ederle did not lead an exciting life in the long term, but in the weeks and months after her achievement, she was a celebrity of proportions that have only rarely been exceeded — even in our own age of instant notoriety. More important, really, is that her accomplishment had a significance that transcended her personal fortunes. Ederle confounded the widely accepted assumption that women were not capable of feats like the one she performed. Her crossing helped to accelerate brewing changes in how women were regarded and what they were permitted to do in a society in which only men were allowed to vote until only five years before. The book was written by Tim Dahlberg with Mary Ederle Ward – the swimmer’s niece – and Brenda Green.

“Perfect” by Lew Paper, is based on Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series between the New York Yankees and the Brooklyn Dodgers. Paper examines the well-worn but still fascinating fact that this feat – achieved only once since the World Series was inaugurated in 1903 – was carried out by a mediocre pitcher whose name would long have been forgotten if it hadn’t been for that day. But Paper makes his book good winter reading for baseball fanatics by devoting each of his 18 chapters to one the half-innings in that game, and focusing each chapter on one of the players who participated. In one instance only, he profiles two players – Jackie Robinson and Gil McDouglald – in a single chapter. In each case, Paper recounts the personal history that brought the player – Mickey Mantle, Enos Slaughter, Gil Hodges, Pee Wee Reese – to that historic moment in sports. Not the least of these figures is Dale Mitchell of the Dodgers who was pinch hitting for starting pitcher Sal Maglie in the top of the ninth when he took the called strike that sealed Larsen’s place in history. Mitchell, who had one of the best batting eyes of his era, thought the pitch was high. So, according to Paper, did most of the Yankees on the field. But, as one baseball wag observed, when the umpire calls strike three on you, even God can’t get you off.

Which president was the best football player?

January 8, 2010

The relationship between baseball and presidents of the United States has been well documented; in fact, there is a room devoted to the subject at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY. The earliest association seems to be with Abraham Lincoln and it is most graphically represented by this Currier & Ives political cartoon, published in 1860, after Lincoln had outlasted three opponents to win the presidency. Lincoln is saying, “Gentleman, if ever you should take a hand in another match at this game, remember that you must have a good bat to strike a fair ball and make a clean score and a home run.”

The relationship between baseball and presidents of the United States has been well documented; in fact, there is a room devoted to the subject at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY. The earliest association seems to be with Abraham Lincoln and it is most graphically represented by this Currier & Ives political cartoon, published in 1860, after Lincoln had outlasted three opponents to win the presidency. Lincoln is saying, “Gentleman, if ever you should take a hand in another match at this game, remember that you must have a good bat to strike a fair ball and make a clean score and a home run.”

How close Lincoln was to the game seems to be a matter of debate, but it is documented that his successor, Andrew Johnson, was the first president to witness an intra-city game and the first president to invite a baseball team into the White House. Among his papers are several honorary membership cards in baseball organizations.

Another president who had a particular connection to baseball was Dwight Eisenhower, who loved the game and said more than once that he would have liked to have played professionally. There is a lingering discussion about whether he did, in fact, once play semi-pro ball under an assumed name — something that would have fouled the amateur status under which he played football at West Point. A number of prominent witnesses said that Eisenhower had admitted to this in later life, but Eisenhower never publicly owned up to it.

Meanwhile, the Christian Science Monitor has looked into the subject of presidents and football — specifically, which president was the best player. The candidates are Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Ronald Reagan.

Even after one gets over the image of Nixon playing football, the answer isn’t as obvious as it may seem.

If you can’t guess, you can read about it at THIS LINK.

“OK, partner. Draw!”

December 17, 2009

Something that always interests me when I attend a live television or radio broadcast is that the people who work in that environment have frame of reference for the passage of time that is very different from mine. I recall, for instance, a stage manager during a break in a broadcast of “The View” telling two stage hands, “I want a potted plant there, and there …. You have twenty seconds.” And the two men calmly fetched the plants, put them in place, and stepped out of camera range just before the show resumed. If anyone told me to do that or pretty much anything else and added, “You have twenty seconds,” I’d be frozen to the spot. I just don’t think or function in those terms.

Well, it turns out that’s nothing compared to Nicole Franks, who thinks in terms of getting a job done in two tenths of a second. Nicole is a fast-draw champion, and judging from a video produced by the Globe & Mail in Toronto, Quick Draw McGraw would have been up against it with Nicole around. It’s literally true that if you blink, you won’t see her move. You can barely see her with your eyes open. You can watch the British Columbian shoot and hear her explain how she does it by clicking on THIS LINK.

You can also read about Bob Munden, who is not only a fast-draw artist but can shoot an aspirin off the head of a nail without hitting the nail. His web site is HERE.

“Hard to get happy after that one.” — Andy Kaufman (“Taxi”)

December 5, 2009

Some baseball players lose their edge over time, but Jim Bunning ain’t one of ’em. He can still put them over the plate, as he demonstrated last week in his verbal assault on Ben Bernanke, who was appearing before a U.S. Senate committee that was considering Bernanke’s nomination to continue as head of the Federal Reserve.

Bunning, a Republican senator from Kentucky and one of the most conservative members of Congress, made a statement at the hearing in which he explained not only why Bernanke shouldn’t be reappointed but why — as my brother might put it — he has no reason to exist. Amid a detailed dissection of what Bunning considers Bernanke’s contributions to the nation’s financial crisis, the senator said: “You are the definition of a moral hazard … Your time as Fed Chairman has been a failure.” The complete statement was published by the Huffington Post at THIS link.

Bunning holds a degree in economics, so for all I know he could be right about Bernanke and about Bernanke’s predecessor, Alan Greenspan, for whom the senator has at least as much affection. On the other hand, his political career has been peppered with bizarre incidents and statements, including his prediction of the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Ginsburg and his public pronouncement that he doesn’t read newspapers and gets all his information from Fox News. His approval ratings, for what they’re worth, are at present in the sewer. He has been unable to raise campaign funds — which he blames on a conspiracy against him within his own party — and he will not run for reelection.

Well, if his political career hasn’t been exemplary, that fact will never outweigh his baseball career. He was one of the very best pitchers of his time and is a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He could throw strikes — oh, could he ever! He struck out 2,855 batters while walking only 1,000. Bunning was one of only 40 pitchers in the history of baseball to strike out the side by throwing nine pitches — all strikes. Try that sometime.

Of men and music

December 2, 2009

So Pau Gasol likes opera, and he doesn’t care who knows it. The Lakers star was invited the first time by his boss — and what can you say? But Gasol was hooked, as a lot of people are, and his acquaintance with fellow Spaniard Placido Domingo has added a personal dimension. The LA Times story about Gasol and Domingo is at THIS link.

I was telling someone the other night about Eleanor Gehrig’s account of how her husband — Lou Gehrig — became an opera buff. She wrote in one of her biographies of Gehrig that she convinced him to go with her on condition that it be kept a secret. In the 1930s, Gehrig had good reason to fear that he would be heckled mercilessly if the other players found out that he had been to the Met.

Eleanor picked the tragic Tristan und Isolde and gave Lou a thorough prepping beforehand. During the performance, she glanced over at him and found him totally absorbed, then with tears in his eyes, and finally “an emotional wreck.”

What Eleanor hadn’t anticipated was that her husband, who had spoken German before he spoke English, was listening to the opera in the original language — not filtered by a half-baked translation such as we are usually subjected to.

Gehrig didn’t only became a frequent visitor at the Met, Eleanor wrote, but she would often come home and find him lying on the floor of their apartment listening to an opera on the radio while he followed along in the libretto.

“I discovered that this was no automaton, no unfeeling giant,” Eleanor wrote. “A sensitive and even soft man who wept while I read him Anna Karenina ….”

I’m guessing the Babe never knew.