Amazon Update No. 10: “Rally ‘Round the Flag, Boys”

June 3, 2015

It may not have been the worst movie we ever saw, but Rally ‘Round the Flag Boys was no bargain at the three dollars and change we paid to watch it on Amazon.

In retrospect, I might have known better from the plot summary and from the presence in the cast of Tuesday Weld, Dwayne “Dobie Gillis” Hickman, Gale Gordon, and Jack Carson. But the top of the bill consisted of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, the director was Leo McCarey, and the film was based on a novel by the same title written by Max Shulman.

Newman plays Harry Bannerman, the owner of a Manhattan PR firm. He commutes by train from an upstate suburb. He and his wife, Grace (Woodward) have two little boys. Harry feels neglected, because Grace is over-committed to civic life in the town. The Bannermans’ glamorous neighbor, Angela Hoffa (Joan Collins) also feels neglected by her husband, who is a network television executive, and she thinks Harry might be the remedy for her loneliness. Harry is close to convincing Grace to leave her committees behind long enough for the two of them to spend a romantic night or two at the St. Regis.

This plan is disrupted by the revelation that the U.S. Army has bought property just outside the town and plans to put a top-secret installation there. Grace is chosen to lead the public opposition to this plan, and she volunteers Harry to handle the public-relations aspects. Meanwhile, Angela makes a play for Harry and, although Harry has no intention of having an affair with her, she manipulates him into a compromising situation that leads to a breakup of the Bannerman household. At the same time, Harry is co-opted by the Army general (Gale Gordon) in charge of the secret project, and forced into taking the government’s side of the argument.

McCarey, a writer-director whose projects included An Affair to Remember, The Bells of St. Mary’s, Going My Way, and the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, was at the end of his career when he made this film in 1958. He made only one more movie—Satan Never Sleeps in 1962.

The movie begins on a crowded northbound commuter train, and there is a fleeting hint that this is going to be a satire on suburban life. In fact, however, it is one, long, heavy-handed slapstick gag. Virtually none of it is funny, and much of it is painful. A drunk scene in which Newman and Collins pretend to laugh uncontrollably goes on much too long to be effective. The nuance of Newman swinging from a chandelier adds nothing. Weld is simply annoying as a girl who has just discovered that she has hormones, and Hickman is ludicrous—not amusing, ludicrous—as a crude leather-jacketed greaser who has his sights on her. Gordon is remarkably restrained, for him, in the role of the general, but Carson, as a boorish and inept Army captain is repulsive.

Farce works only when the audience can accept the premises on which it is built, and that isn’t possible with this film. For example, we are expected to believe that the Army could construct a missile-launching site—complete with a missile and a chimpanzee passenger—without the knowledge of the people who live nearby.

I don’t know what else three dollars and change will buy, but spend it almost anything but this movie and you’re bound to come out ahead.

Amazon Update No. 9: “The Best of Men”

April 21, 2015

I am not oblivious to the expressions of disdain that come over my friends’ faces when I mention that I like to watch Dancing with the Stars. But I am undeterred, because I am still fascinated watching men and women with little or no dance experience take on the rigors of learning and performing demanding routines. Even those who last only a few weeks before being eliminated usually remark that they have achieved things they never would have thought possible. And as interesting as this is with respect to able-bodied people, it rises to the level of inspiring when the dancer has a physical disability. There is no better example of that than Noah Galloway, a contestant in the current season, who lost his left arm and leg while serving in Iraq with the U.S. Army. Sgt. Galloway, who is still in the mix as the season heads into its final weeks, has turned in some thrilling performances with his partner, professional choreographer Sharna Burgess.

This potential we human beings have for resiliency despite even catastrophic illness and injury was the theme of The Best of Men, a 2012 BBC television movie about Dr. Ludwig Guttmann who fled the Nazi persecution of Jews in Germany and settled in England where he was given charge of servicemen who were hospitalized with spinal injuries. Dr. Guttmann found that care of these men consisted of making them as comfortable as possible until they died. This approach exacerbated the pessimism, depression, and anger that naturally accompanied such injuries. Dr. Guttmann proposed that physical activity, not maintenance care, was what these men needed, and that it would help them to take their places in the mainstream of society. Over the objections of some of his colleagues and staff, he got the men involved in vigorous activity such as basketball and javelin throwing and even took them on jaunts to a local pub. When World War II was over, Dr. Guttmann organized national wheelchair sports competitions which eventually evolved into the Paralympic Games. The closing credits note that Dr. Guttmann, who became a British citizen, was knighted for his achievements.

This film has an excellent cast, led by the veteran actor Eddie Marsan as Dr. Guttman; Rob Brydon as Corporal Wynne Bowen, whose dark humor masks his insecurity about his ability to relate sexually to his wife; and David Proud as Jeremy, whose circumstances are complicated by a disappointed father who would consign him to a nursing home.

Amazon Update No. 8: “Iris”

January 18, 2015

Having seen the ravages of Alzheimer’s Disease up close — having lived with them actually, we don’t go out of our way to see the subject dramatized. The other night, however, we were glad we stumbled on Iris, a 2001 movie starring Judi Dench, Jim Broadbent, Kate Winslet, and Hugh Bonneville. This film is based on the life of Iris Murdoch, a prominent British novelist and philosopher in the second half of the twentieth century. While she was a young woman teaching at Oxford, Murdoch fell in love with another Oxford academic, John Bayley, and eventually married him. It was what Puccini’s librettists might have called “a strange harmony of contrasts. Winslet was confident, high-spirited, articulate, and promiscuous, and Bayley was awkward, stuttering, shy, and virgin.

Their story, based on Bayley’s written accounts, is told in turns by flashbacks to the tumult of their early life together and a portrayal of the gradual deterioration of the elderly Iris’s mind. At the center of the story is John Bayley’s enduring love for this woman, even when her dementia frightens him and strains his patience. Dench and Winslet play the elder and younger Iris, and Broadbent and Bonneville play the elder and younger Bayley. This casting was inspired, because in both cases the premise that we are watching the same people at different stages of their lives is convincing. The quality of the performances is reflected by the fact that, among many accolades, Jim Broadbent won an Oscar and Judi Dench and Kate Winslet were nominated. Why Hugh Bonneville wasn’t nominated I can’t imagine. Those who are familiar with him in vehicles such as Belle and Downton Abbey will learn something about his range by watching him in this film. Incidentally, fans of Downton Abbey and The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel might be pleased to see Penelope Wilton’s performance in a significant supporting role in Iris.

Amazon Update No. 7: “Big Trouble”

January 4, 2015

I told one of my daughters the other day that she should see The In-Laws, the 1979 film starring Peter Falk and Alan Arkin. It has to be one of the funniest movies of its kind. Coincidentally, as Pat and I were surfing for a movie to watch on the following night, we came across Big Trouble, a 1986 film also starring Falk and Arkin and including Charles Durning, Robert Stack, Beverly D’Angelo, and Valerie Curtin. We watched it. We were disappointed. I have read that this movie, the last directed by John Cassavetes, is a spoof of Double Indemnity and that it contains multiple references to other classic movies. In fact, the commentator on the IMDb website recommends that a viewer see some of these films—and others directed by Cassavetes—before viewing this one. That’s too much work, but I can verify the commentator’s prediction that a viewer who doesn’t undertake the prerequisites is unlikely to understand or appreciate Big Trouble.

Arkin plays Leonard Hoffman, an agent for a large insurance company, whose wife, Arlene (Valerie Curtin), is hell-bent on sending their musically talented triplet sons to Yale. But an expected scholarship did not materialize, and Leonard is becoming unstrung under the pressure of his wife’s ambition for the boys. While this crisis is simmering, Hoffman is asked by a blonde beauty named Blanche Rickey (Beverly D’Angelo) to make a house call to write a homeowner’s policy on the mansion she occupies with her adventurer-husband, Steve (Peter Falk). She tells Leonard that Steve’s health is very fragile; in fact, he isn’t likely to live much longer. Leonard, in turn, marvels at the fact that there is no life insurance policy on Steve. From this conversation there flows a complicated and wacky chain of events through which we learn—as though life hadn’t told us so often enough—that things aren’t always what they seem.

There are some laughs in this movie—many of them emanating from the combined personalities of Falk and Arkin—including a scene in which Steve offers and Leonard reluctantly accepts a glass of “sardine liqueur,” something that Steve assures Leonard is almost impossible to find. But the movie overall is bizarre and unsatisfying—unless, of course, you’ve done your research.

See The In-Laws.

Amazon Update No. 6: “The Other Sister”

November 20, 2014

Movies that accurately portray the lives of people who have mental disabilities are important. Such movies, by helping the general population better understand the exceptional people in their midst, can create a healthier and more constructive environment for everyone. The Other Sister,’ a 1999 film starring Diane Keaton and directed by Gary Marshall, tried to do that but fell on its face. In fact, it was embarrassing for me to watch, and it should have been embarrassing for the actors to perform.

The “other” sister of the title is Carla Tate, played by Juliette Lewis, who is mentally challenged in some way but who is bright and personable and eager to live independently. Carla is the youngest of three daughters of well-off parents, Elizabeth and Radley, played by Diane Keaton and Tom Skerritt.

At the beginning of the film, Carla has successfully completed the course of study at a private boarding school and is returning to her family’s home. She wants to get on with her life (and by that she means get training at a public polytech school, get a job, and get an apartment), but Elizabeth has no confidence in her daughter’s ability to do anything but live under the protection of her parents. Radley — who seems to have licked a drinking problem — is a little more willing to let Carla stretch. Carla does go to a tech school, and there she meets Danny McMann (Giovanni Ribisi) who, of course, is also mentally challenged and, it seems, less bright and emotionally stable than Carla. The two strike up a friendship and then fall in love and then become sexually active — an aspect of their story that the filmmakers handled with exquisite clumsiness. Carla wears Elizabeth down enough to get an apartment, but Danny isn’t doing as well in school, and his absentee father cuts off funding for any further education. There is a painful scene in which Danny attends a country club Christmas party with Carla and her parents, is intimidated by the surroundings, gets hopelessly drunk, grabs the bandstand microphone and blurts out his feelings for Carla and the fact that the two have been having sex. She is furious at the crowd for laughing at her, as she interprets their reaction, and at Danny for embarrassing her. The next we see of Danny, he is on a train heading home, wherever that is.

Cut to the wedding ceremony of the second of the three daughters. Marshall, perhaps to demonstrate that the spirit of Laverne and Shirley is never quite exorcized from his soul, brings Danny back, in the balcony of the church, of course, from whence he interrupts the nuptials with a parody of The Graduate. The young couple, now reunited, want to wed, but Elizabeth won’t consent. Carla and Danny are determined to marry with or without Elizabeth’s blessing or presence, but the worth reader can no doubt anticipate how that turns out. As if to test how much an audience can tolerate in a 139-minute movie, Marshall and the other writers arrange for Danny, who was a kind of gofer for the polytech’s marching band, surprise Carla outside the church with the band in full regalia marching by and playing “Seventy-six Trombones.”

I guess the filmmakers were concerned that this movie would not seem socially relevant, and so they included a subplot in which Elizabeth is estranged from her third daughter, who lives in a gay relationship. Guess what happens at the end.

The most annoying thing about this movie is that it treats a serious subject like a sit-com. The annoyance is aggravated by the patronizing portrayals of both of the young people—although Juliette Lewis does her best with what she was given to work with—and by the improbable and even slapstick scenes. Marshall doesn’t seem to know what he wants to do with those characters, or maybe he’s simply not competent to deal with such personalities. How else to explain that on one hand Carla is presented to us as mature, confident, and determined, while on the other hand she accompanies her mother to a benefit event at an animal shelter and starts barking at the dogs being housed there and ultimately turns them loose. The sequence in which a bartender at a high-end country club serves an obviously troubled young man one powerful drink after another stretches credibility to the breaking point. A scene in which Elizabeth comandeers a golf cart to chase a distraught Carla across the country club lawns is hopelessly absurd. And Keaton’s portrayal of the inconsistently up-tight Elizabeth can set one’s teeth on edge.

Roger Ebert, of happy memory, commenting about this film, cited Jean-Luc Godard’s observation that the best response to a bad film is to make a good film. In this case, Ebert wrote and I agree, that film is Dominick and Eugene. Don’t see this one; see that one.

Amazon Update No. 5: “The Holiday”

November 12, 2014

I met Shelley Berman in 1972. He was staying in Bernardsville, New Jersey — I think it was Mike Ellis’s house — and appearing in a production of Neil Simon’s Last of the Red Hot Lovers at the Paper Mill Playhouse in Millburn. Berman had become widely known because of his television appearances. His signature routine was sitting on a stool and talking on an imaginary telephone — a bit he put his stamp on before Bob Newhart used it in his own act. I had always thought of Berman as a kind of reiteration of Oscar Levant. I never met Levant, but Berman’s often dour persona reminded me of what I had read about the pianist-composer. I also think that certain points in their lives, they resembled each other physically. I found Berman to be articulate. I remember quite well the case he made about the damage critics can do to performers’ careers. It was something he had experienced himself and had thought a lot about; he could have made that argument before a jury.

I bring up Shelley Berman because we saw him the other night in a 2006 movie, The Holiday. I watch movie credits right to the end, and that’s how I discovered that Berman was in the movie. He had a small role, and I hadn’t recognized him. He was 82 years old when he made that film. But when I saw his name in the credits, I went back into the movie to have a look. I wouldn’t have known him, but the point is that he was a perfect choice for the part he played. And that — the casting — is what makes this movie worthwhile.

The Holiday, which was produced and directed by Nancy Meyers, is about two women who are unhappy in love. Iris Simpkins (Kate Winslet), who writes a society column for The Daily Telegraph of London, has been in love with a colleague for years. He is an affectionate and manipulative friend; he’s also engaged, and there is no prospect for him to return her passion. Meanwhile, frenetic Amanda Woods (Cameron Diaz), who owns and operates a lucrative Los Angeles company that makes movie trailers, finds out that her live-in lover has been having an affair with his secretary. Both women abruptly decide to take a holiday to assuage their anguish and, under the only-in-the-movies rule, they end up swapping houses. The outcome is exactly what you’d expect — in a movie.

But although the plot is obvious and implausible, the casting decisions were impeccable and the result is a very entertaining movie. Winslet and Diaz are perfect as the ingenuous Iris and the frantic Amanda. Jude Law is disarming in an unusual role for him; he plays Iris’s brother, Graham,who makes Amanda’s visit to England worthwhile. Eli Wallach, who was 90 years old when this film was shot, has a tour de force as Arthur Abbott, a retired screen writer with whom Iris develops a warm relationship that revs up the lives of both parties. Shelley Berman plays a buddy of Abbott. The most ingenious stroke of all was the choice of Jack Black as Miles, a sympathetic Hollywood composer who shares with Iris a weakness for the wrong lovers. The script was written with Winslet, Diaz, Law, and Black in mind. Any one of us could had written it, as far as the story line goes, and the reviewers had a few things to say about that, but the movie with its stable of charming characters still made money.

Dustin Hoffman has a brief uncredited cameo in this film. It occurs when Miles and Iris go to a video store and are discussing The Graduate. Hoffman appears as a customer who overhears their conversation and reacts with a whimsical smile. Hoffman has said that he noticed all the cameras and lights at a Blockbuster store and stopped to find out what was going on. He ran into Meyers, whom he knew, and she wrote him into the scene.

Shelley Berman performed one of his telephone routines on Judy Garland’s television show. It is introduced by Garland and a short musical number. To see it, click HERE.

Amazon Update No. 4: “A Walk in the Spring Rain”

October 15, 2014

Ingrid Bergman and Anthony Quinn should have quit while they were behind. These two giants of the screen appeared together in the 1964 film The Visit, and it was a disaster. We didn’t know that before we watched their next joint venture, A Walk in the Spring Rain, released in 1970. This film, based on a novel by the same name by Rachel Maddux, has the disadvantage of never making sense.

Bergman plays Libby Meredith, a New York City woman whose husband, Roger (Fritz Weaver) is a college professor. Roger is under pressure to publish an academic work, so he takes a sabbatical, and the couple repair to a rented house in rural Tennessee where Roger plans to hold forth on some aspect of the Constitution of the United States. This move occurs while the Merediths are in the midst of a disagreement with their married daughter, Ellen (Katharine Crawford), who wants to attend law school but isn’t getting either encouragement or any offer of material assistance from her parents. The film doesn’t help us understand the couple’s chilly response to their daughter’s ambition. The rental house is overseen by a local man, Will Cade (Quinn), who immediately takes a shine to Libby and makes no attempt to hide it. He pursues her right under Roger’s nose until she succumbs. The problem is that it is not clear why she succumbs. We had the feeling that we were supposed to think she was bored with a husband who was absorbed in his academic career, but Roger is portrayed in the film as being attentive and even playful with her.

It also strains belief that Libby and Will carry on this affair while Roger is not only unaware of it but happily lets his wife go off on jaunts with this earthy guy who is always leering at her and making suggestive remarks. Not everyone is as blind as Roger, though, and the relationship between Libby and Will eventually explodes in lethal violence. Even after that, the pair are able to keep their liaison a secret from Roger. In movies and plays about infidelity, I like to have some sympathy for the transgressors, and that’s usually because I have no sympathy for the offended partner. But this story gives me no reason to dislike Roger or even Will’s eccentric spouse, Ann, played by Virginia Gregg. On the other hand, Quinn doesn’t come across as attractive or endearing — although I think director Guy Green was going for that — but rather as a predator who has no regard for anything but his own desires.

This movie was filmed in Tennessee and it’s premiere was held in Knoxville. Ingrid Bergman sat next to Rachel Maddux during the screening. The TCM web site quotes from Bergman’s autobiography her account of this event: “(A)ll through the film she was saying to me, ‘What is this?…What happened to the scene when she?…This isn’t meant to be here…this is later…Haven’t they understood that?’ …I didn’t know what I could do to help her. The book had been so well written, full of the country and the true feelings of a woman in this situation…and now poor Rachel Maddux had seen her book go down the drain. So she went to the ladies’ room and cried. I went after her and tried to comfort her…The film had been a good try. We’d started off with such high hopes. I thought maybe we could do a film with that elusive feeling which Brief Encounter [1945] had. We’d worked hard. We’d done our best and at the end of it we’d made Rachel Maddux cry.”

“Surrounded by assassins!”

August 28, 2014

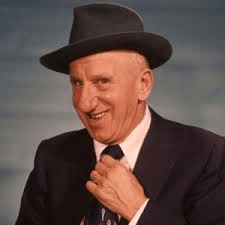

Two crossword puzzles that I recently completed had clues that referred to Jimmy Durante. In one, the solution was Durante’s surname; in the other, the solution was his nickname, “Schnozzola.” Designers of crossword puzzles seem to assume — accurately, for all I know — that theirs is an aged audience. But for the annual rebroadcast of Frosty the Snowman, few people today would ever hear Durante’s voice. My guess is that few people under forty years of age know who he was. This is a natural consequence of the passage of time and of changing tastes in entertainment. Durante was a talented jazz pianist, comedian, and all-around showman. He also set a standard for humility, decency, and generosity. He probably was one of the most recognizable stars of his time, and his “time” lasted for fifty years.

Two crossword puzzles that I recently completed had clues that referred to Jimmy Durante. In one, the solution was Durante’s surname; in the other, the solution was his nickname, “Schnozzola.” Designers of crossword puzzles seem to assume — accurately, for all I know — that theirs is an aged audience. But for the annual rebroadcast of Frosty the Snowman, few people today would ever hear Durante’s voice. My guess is that few people under forty years of age know who he was. This is a natural consequence of the passage of time and of changing tastes in entertainment. Durante was a talented jazz pianist, comedian, and all-around showman. He also set a standard for humility, decency, and generosity. He probably was one of the most recognizable stars of his time, and his “time” lasted for fifty years.

I wonder how many people who see the 1992 film Scent of a Woman catch the reference to Durante. In that film, retired and blind army Lt. Col. Frank Slade, who is bent on suicide, is forced off the ledge, as it were, in a violent struggle with a prep school student named Charles Sims. When the climactic scene winds down, the exhausted Slade, played by Al Pacino, mumbles in a hoarse voice, “Did you ever have the feeling that you wanted to go, but still have the feeling that you wanted to stay?” Even before that line was appropriated for Pacino’s Oscar-winning role, it had been appropriated to express profound ideas about life and death — and particularly about the transition from one to the other. But it didn’t start out that way. Far from originating in deep thought, the line was written and made famous by the antithesis of deep thought, Jimmy Durante. It’s on the order of Groucho Marx’s trademark tune, “Hello, I must be going.” Durante sang the lyric as early as 1931 in a long-forgotten movie, The New Adventures of Get Rich Quick Wallingford. He sang it to Monty Wooley in the 1942 film version of The Man Who Came to Dinner. And he sang it again in the 1944 film Two Girls and a Sailor. In that case, as on many other occasions in his long career, he used it as an introduction to another of his compositions, “Who will be with you when I’m far away?”

To see Pacino deliver the line and Durante sing it to Monte Wooley, click HERE.

To see Durante’s performance in Two Girls and a Sailor, click HERE.

Robin Williams

August 12, 2014

The genius of Robin Williams first sunk in for me when we saw him in the motion picture Awakenings in which he played a character based on the neurologist Oliver Sacks.

We didn’t see that film principally because Robin Williams starred in it but because we were interested in the topic. Sacks pioneered the use of the drug L-Dopa by treating a group of patients who had been in a catatonic state for decades as a result of an epidemic of encephalitis that lasted from 1917 to 1928. But we were impressed by Williams’ portrayal which was very understated. And it was only later, when we saw an earlier documentary with the same title, that we realized how well the often manic Williams had captured the shyness of Dr. Sacks.

The breadth of his range was one of the wonderful things about Robin Williams. Recently, we happened to watch again the hilarious but poignant movie Bird Cage in which he co-starred with Nathan Lane. In spite of the over-the-top humor laced through that movie, Williams’ character was restrained, and the contrast with Lane’s flamboyant character is an important reason why the film works so well.

Pat and I had a chance to chat with Robin Williams in 1998 at a party following the New York premiere of the movie Patch Adams, in which Williams played the unorthodox doctor who wanted to use humor in the treatment of patients. At the invitation of our friend Marvin Minoff, who co-produced that film, we attended the premiere at the Ziegfeld Theater and then the party at Four Seasons. We noticed Williams standing alone, so we approached him, intending only to compliment him on his performance, but he seemed willing to talk, so we willingly obliged. The conversation was so casual that I can’t recall details, except that he spoke of his mother, describing her as his first audience. He was subdued, but Pat and I agreed afterward that he was remarkably accessible for a person of his stature and that he seemed to be pleasant to the core, which, in its way, is as precious a quality as any other.

In one of those coincidences that one wouldn’t dare hope for, we finished our conversation with Robin Williams and spied Dr. Oliver Sacks, apparently trying to hide among the leaves of a rubber tree plant. I had read all of the books he had published up to that point, so we moved on to what turned out to be another conversation for another post.

One of Robin Williams’ foils in Patch Adams was played by Phillip Seymour Hoffman, who also struggled with internal demons and died tragically. You can view both actors in a scene from that film by clicking HERE.