Books: “Helga’s Diary”

April 1, 2013

The dimensions of the Holocaust are brought home by the fact that the stories of individual victims are still emerging 67 years after the end of World War II. One example is Helga’s Diary: A Young Girl’s Account of Life in a Concentration Camp. The author is Helga Weiss, whose family were prisoners at Terezin, a concentration camp in what was then Czechoslovakia. Helga never heard of her father, Otto, or a boyfriend she met in camp, after they were dispatched from Terezin on one of the Nazi “transport” trains, but she and her mother, Irena, survived, despite being sent to the Auschwitz death camp at one point shortly before Germany was defeated.

Helga kept the diary during the years at Terezin (1941-1944), beginning when she was 11 years old. When she knew that she and her mother had been selected for one of the dreaded transports, she gave the diary and drawings and paintings she had done to her uncle, who was assigned to work in the finance office at Terezin. He hid the materials by bricking them up in a wall, and he recovered them after the war. When Helga and Irena had returned to their native Prague, Helga recorded, writing in the present tense, her recollections of their experiences after they left Terezin.

Some of the illustrations Helga did during her ordeal are included in this book. She became a professional artist after the war.

Terezin was a unique enterprise for the Nazis. It was not a camp as such but a Czech town purloined for use as a ghetto. The Nazis incarcerated a lot of writers and musicians there because Terezin was used as a showplace to hoodwink international authorities such as the Red Cross into thinking that Jewish culture was thriving in the Third Reich. My longtime colleague in newspaper journalism, Mirko Tuma, was one of the young Czech intellectuals who were sent to Terezin.

An orchestra of prisoners gives one of the concerts that on the one hand were encouraged by the Nazis and on the other hand helped the victims maintain their sanity.

Mirko told me that reciting poetry, writing and performing plays, and performing musical works helped the prisoners at Terezin maintain their sanity.

But although the Nazis went to a lot of trouble to create a faux town with shops and other amenities — including a school with neither teachers nor students — as a veneer for outside visitors, Helga vividly describes the hunger, thirst, illness, cold, heat, vermin, and human brutality that characterized life in the camp and at the other stops on her odyssey.

She also describes the fear, the uncertainty, the desperation that daily beset the prisoners. They worried constantly about being included in the frequent transports that carried people to God knows what fate.

And Helga, of course writes about the longing for the life that was abruptly taken away from her, of the simple comforts of her home and of Prague itself.

We learn in this diary, which has been translated from the original Czech text, that a young girl had to learn not only to survive but to connive and barter in the camp. She became adept at grabbing scraps of food, even though she knew the possible consequences. Indeed, she saw a boy beaten for taking a single cucumber peel.

We also learn that although she despaired at times, Helga had a strong spirit that wouldn’t let her capitulate to the Nazis.

“(T)here’s no reason for crying,” she writes. “Maybe because we’re imprisoned, because we can’t go to the cinema, the theater, or even on walks like other children? Quite the opposite. That’s exactly why we have to be cheerful. No one ever died for lack of a cinema or theater. You can live in overcrowded hostels . . . on bunks with fleas and bedbugs. It’s rather worse without food, but even a bit of hunger can be tolerated. … only you mustn’t take everything so seriously and start sobbing. They want to destroy us, that’s obvious, but we won’t give in. . . .”

Books: “Explosion at Morgan”

March 28, 2013

Residents of South Amboy leave the city on foot as fires and explosions rock the Gillespie shell-loading plant.

During the four decades I spent covering the news of Central New Jersey, there were sporadic stories about artillery shells being unearthed up and down the coast in Middlesex and Monmouth counties. These were the lingering legacy of a catastrophe that occurred in 1918, an event described in Explosion at Morgan: The World War I Middlesex Munitions Disaster by Randall Gabrielan. The title refers to a series of fires and explosions at the T.A. Gillespie Loading Co., a shell-loading operation, on October 4 and 5, 1918 — just a few weeks before the end of World War I.

The plant, which was located in the Morgan section of Sayreville, was one of four identical facilities hastily built in New Jersey to supply the firepower needed by the allied armies in Europe. Operations at the plant were overseen by U.S. government inspectors

The loading of shells required the handling and processing of huge amounts of TNT and ammonium nitrate, which were combined and heated to produce amatol, a highly explosive material. There is no certainty as to what sparked the calamity, but Gabrielan writes that the first explosion probably occurred in a kettle in which 2,600 pounds of amatol was being brewed.

Once the trouble started, it spread into chaos, with fires raging and shells flying in all directions. The concussions caused property damage over a wide area surrounding the plant, but particularly in the City of South Amboy, where virtually every window was broken. People started fleeing the city simply out of fright, but eventually authorities ordered an evacuation. There were at least 100 people killed in the plant, although the actual total is not known because some of the victims were vaporized in the explosions. Gabrielan also reports that there were about 150 injuries.

This book is carefully researched and precisely written, and its value is not only in its reconstruction of the Gillespie disaster, but in putting both the Gillespie plant itself and the explosions in the wider context of the history of that time. Gabrielan points out that, despite the occasional recovery of a shell, the dramatic and destructive incident has largely faded from the collective memory of the community that was affected by it.

Books: “Words from the White House”

March 20, 2013

When we were watching episodes of Downton Abbey on a DVD, we turned on the English subtitles, because we had trouble understanding a couple of the actors — particularly Rob James-Collier as Thomas Barrow and Sophie McShera as Daisy Mason.

It turned out that while some of our difficulty with the dialogue had to do with the one actor’s mumbling and the other one’s accent, some of it also had to do with the vocabulary itself — British terms that we did not know.

Most of us are familiar with terms like “lorry,” “loo,” and “lift,” but we saw others in the captions that we had never heard before.

It was to be expected that the English used in Britain and the English used in the United States would evolve differently, but I learned recently that that didn’t happen only over time but was done deliberately, on our side of the ocean, soon after the American Revolution.

That’s what Paul Dickson reports in his book Words from the White House, which is a compilation of words and phrases that either were either coined or made popular by presidents and other prominent Americans.

According to Dickson, an 18th century sentiment shared by Thomas Jefferson and Noah Webster, was that Americans had to craft for themselves a language that was distinct from the “king’s English.”

Webster was so confident that this goal could be achieved that he wrote in 1806 that “In fifty years from this time, the American-English will be spoken by more people than all the other dialects of the language.”

Part of the process by which language evolves is “neologizing” — that is, inventing words or phrases from whole cloth.

Dickson writes that the word “neologize” was itself neologized by Jefferson in 1813 in a letter to John Adams.

So Theodore Roosevelt, who — for my money — is disproportionately represented in this book, was neologizing when he invented the term “pussyfooter,” and his distant cousin FDR was doing the same when he created the useful word “iffy.”

Some presidents have been accused of using non-standard terms, not because they were being inventive but because they didn’t know any better.

In this regard, for instance, Dickson mentions Warren G. Harding and George W. Bush.

Harding has often been ridiculed for his 1920 campaign promise of a “return to normalcy,” but Dickson points out that the word “normalcy” had been already in use in several fields, including mathematics.

Harding’s innovation was to give the term a political meaning — and, the author reminds us, it worked.

The second Bush — who could be hard on English — was kidded mercilessly for his used of the term “decider” which he applied to himself when the press asked him about calls for the resignation of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld (“I’m the decider, and I decide what’s best.”) Dickson gives Bush credit for coining this word, but apparently the author didn’t check a dictionary: that word was around before George Bush was president, meaning exactly what he used it to mean.

Books: “Emancipation Proclamation”

March 12, 2013

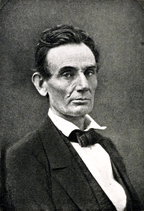

The recent movie Lincoln is serving an important function if it adds some balance to the public perception of the 16th president. No film that I have seen has presented Abraham Lincoln in such realistic terms, and the decision to focus on his campaign to get the 13th Amendment enacted was inspired, because that aspect of Lincoln’s presidency is not well known.

The recent movie Lincoln is serving an important function if it adds some balance to the public perception of the 16th president. No film that I have seen has presented Abraham Lincoln in such realistic terms, and the decision to focus on his campaign to get the 13th Amendment enacted was inspired, because that aspect of Lincoln’s presidency is not well known.

In a way, Lincoln is a victim of his own success. Under his watch, the Union was preserved and human slavery was outlawed in the United States. As a result, Lincoln is enshrined in the national memory as a miracle worker, a savior, almost super human. The apotheosis began almost the moment the public learned of his death.

Among the titles applied to Lincoln is “great emancipator,” but the sobriquet doesn’t reflect Lincoln’s internal struggle and his political struggle over the notion that the federal government should free the millions of people who were being held in bondage in the South when the Civil War erupted.

In Emancipation Proclamation: Lincoln and the Dawn of Liberty, Tonya Bolden spells out the hazardous route Lincoln traveled to his decision to issue the document that fixed his image in history.

In Emancipation Proclamation: Lincoln and the Dawn of Liberty, Tonya Bolden spells out the hazardous route Lincoln traveled to his decision to issue the document that fixed his image in history.

The book is marketed by the publisher, Abrams, as being for young readers but the clear and concise treatment would be serviceable for any adult who wants to catch up on this topic.

Lincoln was progressive for his time. He hated human slavery and would have abolished it if he thought he could. But the relationship between the states and the federal government was still evolving in the mid 19th century, and Lincoln didn’t think Constitution gave the federal government the power to interfere with slavery where it already existed.

Inasmuch as the Civil War erupted shortly after and largely because of Lincoln’s first inauguration,he was preoccupied with one thing, and that was saving the Union. He said in so many words that whatever he did about slavery — abolish it, modify it, leave it alone — he would do only because it would save the Union. In the end, he was true to his word, because the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared free only those people who were being held as slaves in states or parts of states in rebellion against the federal government, was a war measure. Lincoln reasoned that he could take that action as commander in chief even if he couldn’t have taken it as a peacetime president. Even then, he hesitated.

Inasmuch as the Civil War erupted shortly after and largely because of Lincoln’s first inauguration,he was preoccupied with one thing, and that was saving the Union. He said in so many words that whatever he did about slavery — abolish it, modify it, leave it alone — he would do only because it would save the Union. In the end, he was true to his word, because the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared free only those people who were being held as slaves in states or parts of states in rebellion against the federal government, was a war measure. Lincoln reasoned that he could take that action as commander in chief even if he couldn’t have taken it as a peacetime president. Even then, he hesitated.

While Lincoln was considering the advisability of freeing slaves as a way of weakening the southern economy, he had to take into account the potential reaction of the border states — slave states that hadn’t left the Union — as well as the reactions of white Union soldiers who were willing to fight to save the Union but not to free black slaves. Meanwhile, he was under pressure from the swelling abolitionist movement to simply put an end to slavery in one sweeping gesture.

Lincoln also gave a lot of thought to what would become of the slaves once they were emancipated, and his thoughts were shaped by the fact that he didn’t believe in the equality of the black and white races and didn’t think black and white people could live together in peace. Accordingly, his solution was to colonize the freed slaves, preferably in South America or West Africa, even though most slaves at that time had been born in the United States. But by February 1865, Lincoln was publicly endorsing voting rights for at last some educated black men.

This is an attractive book — an art book, really — richly illustrated with images from the period and embellished with break-out quotes from prominent men and women with an interest in the subject of emancipation.

Books: “The Pope’s Jews”

February 12, 2013

I don’t know if this is still true, but when I was at the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri, visitors were invited to write in a large book their opinions of President Harry S Truman’s decision to deploy the atom bomb against Japan in 1945. My opinion is that it’s easy to make Harry Truman’s decisions if you’re not Harry Truman. The same thing can be said for all such figures, including Pope Pius XII.

A great deal has been written about what the pope did or did not do with respect to the Jewish people who were being systematically exterminated by the Nazis during World War II. The latest contribution, if it can be called that, is Gordon Thomas’s book, The Pope’s Jews, which is designed to show that Pope Pius was clear in his condemnation of the Nazi regime and that he was directly involved in a variety of schemes to either help Jewish people escape from Italy or hide them in church properties, including the Vatican itself, during the German invasion.

The best that can be said for this book is that it is superfluous and that it is so badly executed as to be an embarrassment to the publisher and an insult to the reader.

Most if not all of what the author reports here has been published before. It has been well recorded that Pius, a former papal nuncio to Bavaria, was confronted with the murderous Nazis, on the one hand, who had a track record for wreaking indiscriminate vengeance whenever they met opposition or resistance, and the godless Soviets, on the other hand, who were eager to extend their dominance over as much of Europe as possible. The pope was also the head of a neutral state, and the safety of untold human beings depended on the guarantees that accompanied that neutrality.

There also has been a great deal written about the various bishops, priests, and nuns who either helped Jewish people get out of harm’s way or hid them in church properties, including the Vatican itself. Among those complicit in this was Sister Pascalina Lenhert, who was both housekeeper and confidant to Pius XII. Many sources have reported that the pope himself was not only aware of these activities but was directly involved in some of them.

Thomas writes about all this, and he also writes in some detail about the Jewish people living in the Jewish ghetto in Rome (most of whom died in a Nazi concentration camp), the Jewish resistance movement in Rome, and those working — and, in many cases, hiding — in a Jewish hospital on an island in the Tiber.

Thomas includes a lot of information about the work of Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty, who had charge of a network of church operatives who hid Jewish people in multiple safe houses.

Most of this, as I say, comes from secondary sources, and that’s what the bibliography in this book consists of. In the several instances in which the writer does refer to primary sources, he provides no footnotes and no reference to those documents in the bibliography.

Moreover, this book is so carelessly written and edited that the quality of such scholarship as there was must be questioned. The author has a maddening fascination with the past perfect tense of the verb and uses it liberally, especially when it’s not appropriate. That plus awkward or downright improper sentence structure makes reading the text a chore.

And then there are the factual errors. St. Paul was crucified (we don’t know how he died, but the tradition is that he was beheaded); St. Paul had a vision of the risen Jesus in Rome (that happened on the road from Jerusalem to Damascus); Pius XII canonized St. Catherine of Siena (that was Pius II in 1461); Pius XII silenced the anti-Semitic radio priest Charles Coughlin (the Vatican didn’t approve of Coughlin, but didn’t take any action against him; he was forced off the air via regulation by the National Association of Broadcasters after he opposed U.S. involvement in what became World War II).

In his apparent zeal to cast the Catholic Church as a friend of the Jewish people, Thomas writes that Pope Pius IV in the 16th century relaxed a variety of restrictions on Jewish life that had been imposed by his predecessor, Paul IV, but the author does not point out that the restrictions were restored by Pius V.

Immediately after a reference to Pius IV, who assumed the papacy in 1562, Thomas writes this: “The Nicene Creed, the core of the church for centuries, would teach that Pontius Pilate was ultimately responsible for Christ’s death sentence, and that it was the gentiles (sic) who had mocked, scourged, and crucified Jesus.” The Nicene Creed dates from the fourth century, not the 16th, and it doesn’t say anything at all about Gentiles as such: it mentions only Pilate. The Apostle’s Creed, which dates from much earlier than the one adopted by the Council of Nicaea, says exactly the same thing about Pilate. Considering the crimes committed against the Jews over the past 20 centuries, those creeds can hardly be used to make the Church look benign. It was the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s that specifically repudiated the idea that the Jewish people had some corporate responsibility for the death of Jesus; that council also forbid the Church to teach that the Jewish people had somehow been rejected by God (see the council’s document Nostra aetate).

In the decades since the Second Vatican Council, the Church has made a serious effort to improve its relationship with the Jewish people and to condemn any form of anti-Semitism. The present pope, who is about to abdicate, has been very active in that area. Although it does seem that Pius XII gets a bad rap from people who didn’t have to deal with the complex situation he faced, there’s no denying the trouble history between the Church and the Jews. It’s good to think that it might all be behind us.

Books: “Hallucinations”

December 30, 2012

I have often had the experience, as I am about to fall asleep, of seeing for a fleeting moment the image of a familiar person and hearing that person speak directly to me. Although I am always aware that the image and the voice are not real, they always seem to be real.

Phenomena of that kind are the subject of a chapter — “On the Threshold of Sleep” — in Hallucinations by Dr. Oliver Sacks, the neurologist and author. In this latest of his many books, Dr. Sacks discusses the wide range of circumstances under which some folks (many folks, as it turns out) see things, hear things, even smell things that do not exist in objective reality. These are not sights, sounds, or aromas that the hallucinator voluntarily conjures up in his or her own mind, but rather the products of extraordinary activity in various parts of the brain.

The hallucinations Dr. Sacks writes about may be associated with medical conditions that include epilepsy, narcolepsy, and partial or total blindness, and they may be associated with the use of certain drugs. What they usually are not associated with, Dr. Sacks writes, is mental illness. In fact, many people who experience hallucinations are aware that what appears real to them is, in fact, not real.

The condition Sacks explores first, setting a context for the rest of the book, is Charles Bonnet Syndrome, or CBS, which was first identified by an 18th century Swiss naturalist. Persons with CBS have deteriorating or deteriorated eyesight, and they have hallucinations that in a sense fill in the gap of visual sensory input. These hallucinations may be superimposed on the impaired visual field or they may fill in the blind spot of people who have lost sight in half the visual field. Sacks provides this contrast between hallucinations of this kind and dreams:

“Dreamers are wholly enveloped in their dreams, and usually active participants in them, whereas people with CBS retain their normal, critical waking consciousness. CBS hallucinations, even though they are projected into external space, are marked by a lack of interaction; they are always silent and neutral—they rarely convey or evoke any emotion. They are confined to the visual, without sound, smell, or tactile sensation. They are remote, like images on a cinema screen in a theater one has chanced to walk into. The theater is in one’s own mind, and yet the hallucinations seem to have little to do with one in any deeply personal sense.”

Dr.Sacks has spent his professional lifetime collecting case histories from his own interactions with patients, from his reading, and from correspondents who have shared their experiences with them. In this book as in most of his previous ones, he uses that knowledge to illuminate the growing understanding of the human brain.

Meanwhile, the subject matter of this book reminded me of the poem by Hughes Mearns:

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

I wish, I wish he’d go away…

When I came home last night at three

The man was waiting there for me

But when I looked around the hall

I couldn’t see him there at all!

Go away, go away, don’t you come back any more!

Go away, go away, and please don’t slam the door… (slam!)

Last night I saw upon the stair

A little man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

Oh, how I wish he’d go away

That poem is called Antigonish because it was inspired by a ghost story in the Nova Scotia city of that name. Mearns, an educator who believed deeply in cultivating the creativity of children, wrote the lines for a play called Psyco-ed while he was a student at Harvard. It was published as a poem in 1922.

Books: “Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man”

December 18, 2012

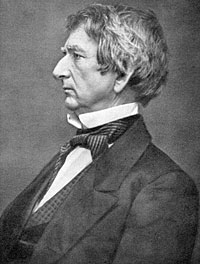

If the Chicago Tribune had it right, William H. Seward was the prince of darkness.

In 1862, when Seward was Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state and the Civil War seemed as likely as not to permanently destroy the federal union, the “world’s greatest newspaper” knew whom to blame. Seward, the Tribune said, was “Lincoln’s evil genius. He has been president de facto, and has kept a sponge saturated with chloroform to Uncle Abe’s nose all the while, except one or two brief spells.” The Boston Commonwealth was about as delicate in its assessment of Seward: “he has a right to be idiotic, undoubtedly, but he has no right to carry his idiocy into the conduct of affairs, and mislead men and nations about ‘ending the war in sixty days.’ ”

This demonic imbecile, as some editors would have it, is the subject of Walter Stahr’s comprehensive and engaging biography, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man. Stahr has a somewhat different take than the Tribune’s Joseph Medill. While Stahr acknowledges that Seward was overly optimistic about prospects for the federal government to prevail over the seceding states, and while he acknowledges that Seward sometimes turned to political chicanery and downright dishonesty, he also regards Seward as second in importance during the Civil War era only to Lincoln himself.

Seward, a former governor of New York and United States Senator, was by Stahr’s account, very close to Lincoln personally, which probably contributed to the rancor directed at Seward from others in the government who wanted the president’s attention. Their relationship was interesting in a way that is analogous to the relationship between Barak Obama and Hillary Clinton in the sense that Seward was Lincoln’s chief rival for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. Seward’s presidential ambitions, which were advanced by fits and starts by the political instigator Thurlow Weed of New York, are well documented in this book. But, as Stahr makes clear, Seward’s disappointment at losing the nomination to Lincoln did not prevent him from agreeing to serve with Lincoln at one of the most difficult periods in the nation’s history nor from serving him loyally.

As important an office as secretary of state is now, it was even more so in the 19th century, because its reach wasn’t confined to foreign affairs. It wasn’t uncommon for the secretary of state to be referred to as “the premier.” At first, Seward’s view of the office might have exceeded even the reality; he seems to have thought at first that he would make and execute policy and Lincoln provide the face of the administration. Lincoln soon made it clear who was in charge, and he and Seward worked well together from then on.

Seward’s service in Lincoln’s administration nearly cost him his life on the night that Lincoln himself was murdered by John Wilkes Booth. One of Booth’s accomplices, Lewis Payne, forced his way into the house where Seward was lying in bed, recovering from injuries he had sustained in a serious carriage accident. Payne, who was a wild man, tore through the place, cutting anyone who tried to stop him, and he attacked Seward, slashing his face. Payne fled the house — he eventually hanged for his crime — and Seward survived.

After the double trauma of Lincoln’s death and Seward’s own ordeal, it would have been understandable if Seward had withdrawn from public life. Seward wasn’t cut of ordinary cloth, however, and he agreed to remain at his post in the administration of Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson. Johnson was an outstanding American in many respects—he was the only southern member to remain in his U.S. Senate seat after secession, and he gave up the relative safety of the capital and took his life in his hands when Lincoln asked him to serve as military governor of Tennessee — but he was not suited for the role that was thrust on him by Booth.

Stahr explores the question of why Seward stayed on during the troubled years of Johnson’s tenure. He infers, for one thing, that Seward agreed with Johnson’s idea that the southern states should be quickly restored to their place in the Union without the tests that the Republican majority in Congress, and especially the “radical” wing of the party, wanted to impose. Stahr also writes that Seward believed that if Congress succeeded in removing Johnson on impeachment charges that were politically motivated it would upset the balance of power in the federal government for decades to come.

I mentioned Seward to a co-worker today, and she said, “of the folly?” She was referring to the purchase of Alaska, which Seward completed during Johnson’s administration. Stahr writes that much of the press supported the purchase of “Russian American” at first, and although the term “folly” was tossed about later, prompted in part by Seward’s further ambitions for expansion, the epithet was never widely used.

Alaska was only one of Seward’s achievements. He was a skillful diplomat who was equipped to play the dangerous game that kept Britain and France from recognizing the Confederate States of America. Although he may have underestimated the threat of secession and the prospects for a protracted war, he was at Lincoln’s side every step of the way—playing a direct role, for instance, in the suspension of habeas corpus and the incarceration of suspected spies without trial. He was not an abolitionist—and in that respect he disagreed with his outspoken wife, Frances— but Seward was passionate about preventing the spread of slavery into the western territories. He believed that black Americans should be educated. He did not support fugitive slave laws and even illegally sheltered runaway slaves in his home in Auburn, N.Y.

Seward was a complicated character who stuck to high moral and ethical standards much of the time, but was capable of chicanery, deceit, and maybe even bribery if it would advance what he thought was a worthy purpose.

A world traveler, he was one of Washington’s leading hosts, known for his engaging manner, and yet with his omnipresent cigar and well-worn clothes he appeared to all the world as something akin to an unmade bed. Henry Adams, who admired Seward, described him as “the old fellow with his big nose and his wire hair and grizzled eyebrows and miserable dress” who nevertheless was “rolling out his grand, broad ideas that would inspire a cow with statesmanship if she understood our language.”

Books: “Isaac’s Army”

November 10, 2012

Warsaw came as a surprise to me. Because of my uneducated impressions of Eastern Europe, I expected the city to be grim, but it was not. Warsaw was lively, handsome, well-swept, festooned with parks, and imbued with the spirits of such as Paderewski, Chopin, and Wojtyla.

Warsaw came as a surprise to me. Because of my uneducated impressions of Eastern Europe, I expected the city to be grim, but it was not. Warsaw was lively, handsome, well-swept, festooned with parks, and imbued with the spirits of such as Paderewski, Chopin, and Wojtyla.

But as satisfying as it was to see the city thriving, it was impossible to escape reminders of its darkest days, when it was occupied and devastated by Nazi Germany — and its Jewish population virtually exterminated — a period that is described in vivid human detail in Matthew Brzezinski’s book, Isaac’s Army.

Brzezinski, who has been a reporter for the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, concentrates in this book on the walled ghetto in which the Nazis confined hundreds of thousands of Jews in subhuman conditions until most of the poor people were either worked to death, killed by hunger and disease, shot to death in summary executions, burned to death in their homes and hiding places, or shipped off to death camps.

I saw remnants of the ghetto in Warsaw, but it seemed almost like an abstract idea. In Brzezinski’s book, however, the depth of the depravity with which the Nazis and their collaborators treated Polish Jews comes through with shocking force.

Brzezinski is particularly interested in a relatively small group of Jewish men and women who recognized from the beginning that the Nazi presence was an imminent danger to their community and were not willing to stand by and let the Germans proceed unhindered. The writer relates the stories of about a dozen individuals who were in that category. They belonged to underground paramilitary organizations that struggled to maintain some semblance of resistance to their persecutors. These folks defied and undermined the Nazi attempt to isolate the Jews and ultimately, in 1943, participated in the uprising that stunned and momentarily humiliated the SS when the “supermen” entered the ghetto with the object of leveling it.

Brzezinski is particularly interested in a relatively small group of Jewish men and women who recognized from the beginning that the Nazi presence was an imminent danger to their community and were not willing to stand by and let the Germans proceed unhindered. The writer relates the stories of about a dozen individuals who were in that category. They belonged to underground paramilitary organizations that struggled to maintain some semblance of resistance to their persecutors. These folks defied and undermined the Nazi attempt to isolate the Jews and ultimately, in 1943, participated in the uprising that stunned and momentarily humiliated the SS when the “supermen” entered the ghetto with the object of leveling it.

Unfortunately, as Brzezinski relates, Polish Jews were not of a single mind about how they should respond to the Nazis or whether they should respond at all. They also were sharply divided over issues such as Marxism and Zionism.

They were frustrated by the fact that so many people and nations were indifferent to their plight, and they had to resort to bribery and subterfuge to accumulate even the poor excuse for an arsenal they had to defend themselves against the combination of Adolf Hitler’s insanity and his military machine. Their situation may have been hopeless to start out with, but Brzezinski shows that some of them would not give up hope or, at least, would persist in their struggle against the Nazis even when hope was gone. While this book, on the one hand, records one of the worst examples of human cruelty, it also records one of the best examples of human resilience. The account of a few score sick and starving Jews escaping the ghetto by stumbling for hours through a sewer laden with human excrement, corpses, and rats is disgusting to the imagination. At the same time, it is uplifting to know that people who would not concede their right to dignity and justice were willing to undergo even that in order to deny Hitler his dream of eradicating Judaism in Europe.