Books: “Worst Seat in the House”

February 13, 2016

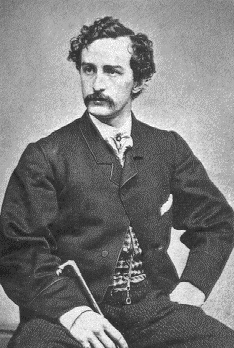

Last summer, I wrote a post here about Scott Martelle’s book, “The Madman and the Assassin,” which was a biography of Thomas “Boston” Corbett, the eccentric soldier who shot John Wilkes Booth. What was interesting about that book, besides the fact that Martelle executed it so well, was the fact that in the 150 years that elapsed since Booth died, no one else had written a book-length account of Corbett’s life. Now, hard on Martelle’s heels, comes Caleb Jenner Stephens, with a rare and perhaps unique book-length account of the life of Henry Rathbone, one of only four people present when Booth murdered Abraham Lincoln. Rathbone, an army major at the time, and his fiancé, Clara Harris, joined Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln at Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865 for a performance of the comedy Our American Cousin.

The only reason the couple accompanied the Lincolns that night was that everyone else who had been invited—notably including General Ulysses S. Grant and his wife, Julia—had declined. The advance chatter that the Grants and the Lincolns might attend together just days after Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia had caused some excitement in Washington, but Julia Grant was one of many people in the capital who could not abide Mary Lincoln, so the Grants avoided the appointment by repairing to New Jersey to visit their children. Rathbone, who was sitting in the rear of the presidential box when Booth entered, confronted the assassin after the murder had been committed and sustained a serious knife wound in his left arm.

Despite the injury, he tried unsuccessfully to prevent Booth from leaping from the box to the stage from whence he made his escape. Rathbone, who came from a wealthy Albany family, later married Clara Harris, who was also his stepsister, and the couple had three children, including U.S. Representative Henry Riggs Rathbone of Illinois. Rathbone recovered from the wound to his arm, but his mental health seems to have been permanently impaired by his experience at the theater and especially by the fact that he had been unable to either prevent Lincoln’s death or keep Booth from escaping. It was unreasonable for Rathbone to assume guilt for this, but the event was so sudden and shocking that reason didn’t play a part in his reaction to it. Stephens makes that argument, in some detail, that Rathbone suffered from what is now known as post traumatic stress syndrome. The author also explores an account of the murder—raised in a contemporary publication—which holds that Rathbone saw Booth enter the presidential box before the murder and rose to ask Booth what business he had there, but was brushed aside as Booth approached the president from behind and fired the fatal shot.

I am not aware that this version appears in any public record. Stephens attributes it to The Public Ledger, a daily newspaper then being published in Philadelphia. According to The Public Ledger, Clara Harris gave this alternative version during an interview with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Stephens gives weight to this account and repeatedly—and, I think, unfairly—refers to Rathbone’s “failure to protect the president.” In one instance, in fact—in a stunning exercise of hyperbole—the author accuses Rathbone of “failing the whole world.”

Rathbone remained in the army until 1879 and retired with the rank of brevet colonel. He and his family were living in Germany on December 23, 1883, when, after many years of psychic and emotional instability, he murdered Clara and tried to commit suicide. He was consigned to a reasonably comfortable asylum in Germany for the remaining twenty-seven years of his life. This book suffers from bad grammar and syntax to a degree that is very distracting. However, Stephens has made a contribution to the literature surrounding the murder of Abraham Lincoln by compiling a chronicle that has been neglected.

Books: “Son of Harpo Speaks”

August 1, 2015

There is a double meaning to the title of this book, which was published in 2010. This is the memoir of Bill Marx, oldest of the four children of Harpo Marx, so the book is, in a sense, Harpo’s son speaking. The title also is an allusion to Harpo Speaks, the 1961 autobiography of the silent comedian, written “with Rowland Barber.”

Harpo Speaks may be the best of the many books about this family, due in part to the detailed memories of Harpo Marx and the writing skills of Rowland Barber, who also wrote The Night they Raided Minsky’s and co-wrote Somebody Up There Likes Me with boxer Rocky Graziano. Son of Harpo Speaks is not in the same class. It’s not that Bill Marx didn’t have a story to tell, or even that he didn’t tell it. It’s that he told it without focus or precision. The grammatical and spelling errors, while trivial as individual faux pas, are distracting in the aggregate. The absence of a professional co-author and a rigorous editor is evident on every page.

Nevertheless, I’m grateful that Bill Marx wrote this book, because it preserves facts and insights about his parents and the rest of the Marx family that might otherwise have been lost. That’s important to me, because I have been a student of the Marx clan since I was about 13 years old and someone gave me a copy of The Marx Brothers by Kyle Crichton, which was published in 1950. I use the word “student” rather than “fan” because I have always been less interested in the Marx Brothers as entertainers than in the Marx family as a phenomenon of the American experience in the twentieth century. I have read most of the other books about them and I have interviewed Miriam Marx, the eldest child of Groucho Marx; Maxine Marx, the daughter of Chico Marx; and Gregg Marx, the grandson of Gummo Marx.

Bill Marx was the first of four children adopted by Harpo and Susan Fleming Marx, and he made his career as a Julliard-trained pianist, composer, and arranger. His account of his relationship with his adoptive parents confirms what one reads in every account of their lives, namely that they were genuinely nice people. Bill Marx unabashedly admired both of them, and he revels in the fact that for many years he served as Harpo’s props manager: “I had to see that the coat he wore was properly prepared for all of his sight gags; the carrot goes into the upper right inside pocket, the telescope must be in the lower left inside pocket, the scissors for immediate availability in the small middle right inside pocket, the rubber chicken accessible in the large left inside pocket, and on and on.”

Once Bill Marx got his sea legs as a musician, he collaborated with his father on several projects, including two albums of Harpo’s performances on the complicated instrument he mastered without a lesson and without the ability to read music. He also wrote arrangements for Harpo’s live performances and TV guest spots.

Bill Marx also devotes considerable space in this meandering book to his personal emotional and psychic history, including his struggle to find and understand his own identity, and the personalities that influenced him, including such icons as Buddy Rich and Margaret Hamilton. He also includes a fascinating account of how he learned the names and sad histories of his birth parents through a chance acquaintance he made at Dino’s, a club in Los Angeles where he was playing piano.

I’m glad to have read this book; my only regret is that I wasn’t the editor.

(Bill Marx presides over an informative and entertaining web site, The Official Arthur Harpo Marx Family Online Collection.)

Books: “The Madman and the Assassin”

June 4, 2015

I don’t know how John Wilkes Booth thought his journey was going to end, but I’m sure Boston Corbett didn’t figure in his plans.

Booth made a sincere effort to get away with murdering Abraham Lincoln. With one of his accomplices, David Herold, he was heading south, hoping to get deep into the former Confederacy where folks might see what he did–sneaking up on a man and shooting him in the back of the head–as something more than an act of cowardice. Like many criminals, however, Booth left a trail, and federal detectives and troops tracked him down to a Virginia farm, cornered him and Herold in a barn, and set fire to the structure. Herold gave up and eventually hanged, but Booth, who was armed, stayed in the burning building. Corbett, an army sergeant, watched the assassin through an opening in the wall of the barn and–as he later said–thinking that Booth was about to fire on the soldiers outside, shot him in almost the same place that Booth’s bullet had struck Lincoln. Booth fell, paralyzed, and died after being removed to the farmhouse porch.

Thomas “Boston” Corbett, the man who killed Booth, is the subject of this engrossing book by Scott Martelle. It’s an important contribution to the history of the epoch surrounding the end of the Civil War and the murder of Lincoln; relatively little has been written about Corbett and some of what has been written has been incorrect. By Martelle’s account, Corbett was a complicated and eccentric character. He frequently worked as a hatter — specifically as a finisher — and that meant that he was exposed to a great deal of mercury. That has led to speculation that mercury poisoning led to Corbett’s peculiarities as it led to the odd behavior of many others. His lifelong vocation, however, was not as a hatter but as a Christian preacher. He was deeply religious in his own way, so much so that Martelle reports that Corbett castrated himself while still a young man in order to spare himself the inclination to sexual sin. His overriding goal was to live as a Christian — as he understood that term — every hour of every day. Whatever his foibles, he performed many acts of kindness in his pursuit of that ideal.

He served four separate hitches in the Union Army during the Civil War, and a colleague later wrote of him, “He was a very religious man, faithful at his post of duty, a good speaker, and a skillful and helpful nurse to those who were ill or in distress, and [he] knew no fear.” Still, he was once court-martialed for walking off his post, and he threatened to kill a fellow soldier in order to dissuade him from picking blackberries on the Sabbath. Corbett thought the war was justified and reportedly had no qualms about killing enemy soldiers, although he prayed for them before pulling the trigger.

At one point, Corbett was an inmate at the notorious prison camp in Andersonville, Georgia. The conditions there were so heinous that they permanently damaged Corbett’s health. He did survive, however, and returned to service, and so was available when a cavalry detachment was sent to hunt down Booth and Herold.

In the wake of Booth’s death, some people regarded Corbett as a hero, and some condemned him. Although there were claims to that effect at the time, Martelle determined that there was no order to take Booth alive. Corbett was in demand as a speaker and, one imagines, as a curiosity, but in the long run he had a difficult time sustaining himself. In desperation, he moved to Kansas and tried his hand at raising livestock and selling the wool from his sheep.

Eventually, he became unglued, was confined to a asylum, escaped, and vanished from history.

If Corbett hadn’t shot Booth, Booth would have hanged anyway. Whether he would have revealed anything to assuage the doubts, which still linger, about the culpability of Mary Surratt and Dr. Samuel Mudd, we can only conjecture. As it is, Mrs. Surratt hanged and Dr. Mudd was sent to the federal prison in the Dry Tortugas Islands off Key West but pardoned after he helped stem a yellow-fever epidemic among the inmates.

But Corbett did shoot Booth, and, like Jack Ruby after him, became a key if shadowy player in a great drama. Martelle, a diligent reporter and a skillful writer, has done us a service by recreating the life of this strange man.

Book: “The Bully Pulpit”

May 31, 2015

Justin S. Vaughn, a political science professor at Boise State University, writing recently in The Times, raised the question of which of Barack Obama’s predecessors have been the best and the worst former presidents. It’s an uncommon way to look at the presidency, and it adds a useful context. Those of us who are only casual observers of history tend to think of the presidents strictly in terms of their time in office and evaluate them accordingly. But, as Vaughn points out, “Our greatest ex-presidents have engaged in important work, sometimes at a level that rivaled their accomplishments in the White House. Our worst ex-presidents, on the other hand, have been noteworthy for taking strong positions against the national interest and consistently undermining their successors for personal and political reasons.”

Vaughn’s choices as the best former presidents included John Quincy Adams, Jimmy Carter, William Howard Taft, and Herbert Hoover. When the Washington Post, in 2014, asked 162 members of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents & Executive Politics section to rank the presidents, Taft was 20th and Quincy Adams 22nd. Carter and Hoover did not place in the top 24. That implies, if one were to take these things literally, that the four best former presidents by Vaughn’s estimation were only middling or worse as presidents.

But Adams, one of only two presidents to be elected to public office after leaving the White House, was a leading member of the House of Representatives for almost 20 years; Carter has devoted himself to promoting human and political rights all over the world. Hoover headed the program to stave off starvation in Germany after World War II and he was appointed by Presidents Truman and Eisenhower to lead commissions that successfully recommended reforms in the operations of the federal government.

Vaughn’s nominees for the worst former presidents include John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and Theodore Roosevelt. The first three did not distinguish themselves as president, but Roosevelt is regularly ranked among the best. He finished fourth in the 2014 survey, following Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Franklin Roosevelt.

I recently got a belated education regarding Taft and Theodore Roosevelt by reading Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book The Bully Pulpit, which is sort of a double biography. The careers of these two men — their whole careers, not only their presidencies — occurred during a critical era in American history in which the nation grappled with the tension between free enterprise and the government’s attempts to prevent large business interests from unfairly controlling whole sectors of the economy. Goodwin paints impressive portraits that convey the personal and political integrity and the spirit of public service that characterized both Taft and Roosevelt. Both men were highly distinguished before they were elected to the presidency. Taft, as Goodwin relates, was mostly interested in the law and hoped to some day serve on the United States Supreme Court. He did not aspire to be president, but accepted the role under the heavy influence of his wife and of Roosevelt, who had promised after he was elected to his second term that he would not seek a third — a promise he lived to regret.

One of the reasons Roosevelt lands in Vaughn’s list of worst former presidents is that he disapproved of Taft’s administration and, forsaking his “two and through” pledge, challenged him for the 1912 Republican nomination and, failing at that, ran for president on a third-party ticket, guaranteeing the election of the Democrat, Woodrow Wilson. Taft, on the other hand, realized his ambition when President Warren Harding appointed him chief justice of the United States, a position in which he served with distinction for a decade.

Although Roosevelt was an egocentric and therefore sometimes childish character, his life and that of Taft, on the whole, were among the most exemplary among American public figures. Goodwin’s account of their careers, by bringing them to life, also brings to life an often neglected epoch in American history.

Books: “The Romanov Sisters”

September 14, 2014

It’s a shame that William Shakespeare didn’t live long enough to know the Romanovs. They would have made a great subject for one of his tragedies. I think of that every time I read about them, and the idea was reinforced by Helen Rappaport’s recent book, The Romanov Sisters. The title refers to the daughters of Nicholas II and Alexandra, the last emperor and empress of Russia. The girls — Olga, Maria, Tatiana, and Alexandra — their brother Alexei, their parents, and several retainers, were murdered by Bolshevik thugs in Siberia in 1918. Rappaport has written about that, but in this absorbing book she focuses on the years from the births of the five children to their deaths. Although the sisters are supposed to be the principal subjects of this book, Rappaport really provides a portrait of the whole family. And her portrait gives the impression, which I have drawn from other books on this subject, that these Romanovs were nice people who were unsuited for their position in life. One example of the character of these people is that Nicholas and Alexandra, unlike most royal couples in that era, married for love and remained deeply in love for the rest of their lives.

NICHOLAS and his children, OLGA, TATIANA, MARIA, ANASTASIA, and ALEXEI in a photograph taken by the empress Alexandra.

One of their overriding obligations was to produce a male heir for Nicholas, but the first four children were girls. One after another, these births sent reverberations throughout Russia where the question of an heir became a preoccupation the moment Nicholas succeeded to the throne. Although they were aware of the implications, Nicholas and Alexandra reveled in the arrival of each of their daughters. When the heir, Alexei, finally did arrive, the euphoria within the family was muted when he was diagnosed with hemophilia — the royal disease. Helping her son became an obsession for Alexandra. In itself that was natural and maybe even commendable, but it exacerbated existing problems with Alexandra’s public image. Among the Russians, she was suspect from the start, because her background was not Russian but English and German. She was a favored granddaughter of Victoria. She frustrated both common and privileged Russians, too, by living an insular life, preferring to hunker down with her immediate family rather than appear in public, even at state occasions where her presence would have been expected.

The Russian gossip circuits, and diplomatic circles, buzzed over the plain, almost homespun manner in which the four grand duchesses dressed, their casual demeanor among the few outsiders they spent time with — notably the sailors and officers on the royal yacht — and the infrequency of the girls’ public appearances. Alexandra’s isolation was a result both of her choice of a lifestyle and of her multitude of real and imagined illnesses, and it was aggravated by her exhausting focus on Alexei’s condition. Her tendency to keep her children close by deprived them of a full social life to the extent that the ostensibly future emperor of all the Russias would frequently shrink from strangers who visited the family’s home. Alexandra’s standing among the Russians, including the royal family, wasn’t improved any by her association with Grigori Rasputin, the enigmatic, unkempt “holy man” who, it seemed to the empress, was the only person capable of easing her son’s suffering. Rappaport is not judgmental in writing about Rasputin, and she provides what for me was new context by including input from Rasputin’s daughter. I also learned from Rappaport that it was not only Alexandra but also her daughters who felt a strong emotional and spiritual attachment to the strange man.

Russians suspected Alexandra’s loyalty because of her apparent aloofness and her British and German origins. And yet one of the most dramatic aspects of her life occurred during World War I when she and her two older daughters took formal training as nurses and worked in hospitals, some of which they themselves established. By Rappaport’s account, this was no publicity stunt, but a serious undertaking, often in gruesome circumstances, including the many amputations performed on soldiers carried back from the front.

Nicholas and Alexandra were complicit in their own undoing because of their firm belief in a divinely sanctioned monarchy, their stubborn adherence to a lifestyle that did not meet the expectations of either their subjects or the international community, and their failure in general to read the signs of the times. Still, it’s difficult to come away from their story without a deep sense of sadness over the waste of what might have been beautiful lives.

Books: “Color Blind”

March 27, 2014

One aspect of my father’s life that I don’t know nearly enough about is the time he spent managing a semi-pro baseball team. He mentioned it now and then, but the only detail I have retained is that his team played a couple of games against a team managed by Johnny Vander Meer. Vander Meer is the only pitcher in the history of major league baseball to pitch no-hitters in two consecutive games. That was in 1938. He also pitched a no-hitter in the Texas League 14 years later.

At the time that my father told me about opposing Vander Meer, I didn’t understand the importance of semi-pro baseball. In fact, I probably didn’t know what the expression meant. In broad terms, there have historically been three categories of baseball leagues: professional, semi-professional, and amateur.The professional leagues are what we know as the major and minor leagues, including the minor leagues whose teams are not affiliated with major league teams. Among the rest, a team is considered semi-pro if even one of its players is paid.

How many were paid and how they were paid varied a lot from time to time and place to place. There were teams sponsored by companies, by local businesses, by civic and social organizations, by towns, and by private individuals. On some teams, every player was paid. On some only a handful. And in circumstances in which the competition was intense, one or more of the players on a team who were paid were ringers recruited from the minor leagues or the Negro Leagues with offers of bigger salaries than the pros were paying.

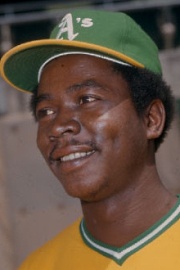

There were semi-pro teams all over the United States and Canada, and many of them could draw crowds in those days when the big leagues were concentrated in the eastern part of the country where they were out of reach for most Americans. Semi-pro ball could provide an especially welcome diversion during the epoch in which the plains were beset by both economic depression and drought. One team in particular is the subject of Tom Dunkel’s book, “Color Blind.” The team Dunkel writes about was based in Bismark, North Dakota in the 1930s; it was not a member of a league, but played against teams in nearby and far-off towns and against barnstorming teams that wandered the landscape trying to make a buck. The Bismark team, so far as we know, didn’t have an official nickname although they are often referred to as the Churchills. That’s a nod to Neil Churchill, a partner in a Bismark auto dealership, an habitual if not addicted gambler, and the owner and frequently the manager of the local nine.

Churchill was devoted to the game and he was competitive. He was constantly striking deals with pro players to give the Bismarks an edge over their opponents. Winning was such a priority with him that he didn’t care what color the players were. In fact, because the pro leagues were more than a decade away from coming to their senses, Churchill was able to attract some talented black players, including Satchel Paige. Paige should have spent his career in the majors, but because of the color line and because of his wanderlust, he’d take the field wherever he got the best offer. In 1933 and in 1935, that offer — a $400 a month and a late-model car—came from Churchill , and Paige bolted from the Negro League team in Pittsburgh and made for Bismark. That was no small achievement for Churchill. Although there is no way to establish the widely held belief that Paige was the greatest pitcher of his time, and perhaps of any time, we know enough about him to know that he was extraordinary. In ’35 he started and won four games and relieved in another when Bismark took seven straight to win the inaugural National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita.

Among the other outstanding black players Churchill recruited were pitcher-catcher Ted “Double Duty” Radcliff, and catcher Quincy Thomas Trouppe (nee Troupe) who, by the way, was the father of prominent poet-journalist-academic Quincy Thomas Troupe Jr.

Churchill led the only integrated organized team in that rough-and-tumble era in baseball, and he got some pushback for his trouble. And Bismark’s black players, of course, had to endure the insults and isolation that the land of “all men are created equal” imposed on many of its citizens then and for more than 30 years after. In his book, Dunkel brings to light a fragment of American history in which the relationship between the people and their national game was much more intimate than it was to become, and by evoking the names of men like Paige and Radcliffe and Trouppe, he reminds us of the crime that was committed for more than six decades against many of its finest practitioners.

Books: “The Art of Controversy”

June 18, 2013

It’s one of the ironies of 19th century history that the same man who gave us the roly-poly image of Santa Claus that warms our hearts every year was also one of the most damaging political cartoonists of his era. But that’s the way it was with Thomas Nast, one of the artists Victor N. Navasky discusses in The Art of Controversy, a meditation on the art and implications of the caricature.

Nast famously set his sights on Tammany Hall, as the Democratic Party machine in New York City was known, and particularly on William M. “Boss” Tweed, a businessman and politician who dominated the affairs of the city largely through his control of patronage in the form of both contracts and jobs.

As Navasky relates, Nast’s work in Harper’s Weekly during the 1871 election campaign is credited with purging city government of the Tammany gang. Tweed and others in his circle were subsequently charged with enormous thefts of public funds and sentenced to prison. Tweed tried to flee, but a Spanish customs official arrested him after recognizing him from Nast’s caricatures.

Tweed was no stranger to criticism, but he famously remarked about Nast’s assaults on him: “Stop them damn pictures! I don’t care a straw for your newspaper articles. My constituents can’t read. But they can’t help seeing them damn pictures!”

The story of Nast and Tweed illustrates many of the points made by Navasky, who is the former editor and publisher of The Nation and a former editor at The New York Times Magazine. One of those points is the power of caricature, which is a form of cartooning that emphasizes or exaggerates distinctive physical characteristics of the subject: Richard Nixon’s ski nose and widow’s peak, for example, or Lyndon Johnson’s ears.

This is neither a technical analysis nor a history, although Navasky reaches back a few centuries in discussing the origins of caricature, noting that Leonardo da Vinci may have originated the form in the 16th century and William Hogarth was one of those who had perfected it in the 18th. This book is more a matter of Navasky thinking through the subject of political cartoons and not necessarily answering all of his own questions about the topic.

The author writes a lot about what makes caricature so effective. How effective? He points out one case in which an artist’s work landed him on Adolf Hitler’s “death list” and another case in which a cartoonist for Arab daily newspapers in Europe and the Near East was assassinated. In a far different vein, he devotes a chapter to the Nazi periodical Die Stürmer, which conducted a relentless campaign to ridicule and demean Jews, with caricature as a principal method. The editor, Julius Streicher, was hanged after the Nuremberg trials, and the cover cartoonist, Philipp Rupprecht, was sentenced to six years in prison, a sentence Navasky thinks was too light.

This potency raises in Navasky’s mind the question of whether political cartooning should enjoy exactly the free-speech protection that the written word has in the United States. He isn’t arguing that it shouldn’t, but he explores significant ways in which the two forms of expression are not identical — including the lasting (and frequently negative) impression a caricature makes and the fact that one can answer words with words (as in a letter to the editor), but can hardly make an effective response to a cartoon.

Navasky writes about editorial decisions (to publish or not to publish) such as the “Danish Muhammads” and a case of his own in which practically his whole staff opposed his choice to print a cartoon that portrayed Henry Kissinger “screwing the world.” This is a provocative book from Alfred A. Knopf about the use of caricature at various times in history and in various parts of the world. I screened editorial cartoons for my newspapers for the better part of four decades, but Navasky’s musings have given me new insights and raised questions that I had never considered.

Last year I reviewed a book about Erik Jan Hanussen, a mentalist and con man who first flourished and then crashed and burned in Berlin during the Nazi era — an Austrian Jew posing as a Danish aristocrat. Hanussen struck me as one of the most bizarre characters in the drama of that time, but he has to make room in the pantheon for a puny Jewish teenager who is the subject of Jonathan Kirsch’s arresting book, The Short Strange Life of Herschel Grynszpan.

Herschel was living with his Polish parents in Hamburg, Germany, when the Nazis came to power. During the run-up to the Holocaust, when Adolf Hitler’s scheme was to make life so unbearable for Jews that they would leave the Third Reich by their own volition, Herschel’s parents became concerned about his wellbeing. Their solution was to send him west when he was 15 years old, and he wound up living with his uncle and aunt in Paris.

Herschel was living with his Polish parents in Hamburg, Germany, when the Nazis came to power. During the run-up to the Holocaust, when Adolf Hitler’s scheme was to make life so unbearable for Jews that they would leave the Third Reich by their own volition, Herschel’s parents became concerned about his wellbeing. Their solution was to send him west when he was 15 years old, and he wound up living with his uncle and aunt in Paris.

During his sojourn, Herschel’s parents and siblings were among about 12,000 Polish Jews who were abruptly taken from their homes by the Nazis and deposited on the Polish side of the border with Germany. From the refugee camp there, Herschel’s sister wrote to him, describing the harsh conditions.

After an argument with his uncle over the question of helping the Grynszpans financially, Herschel bolted from the apartment and, on the following day, bought a revolver, entered the German embassy on a pretext, and shot a young diplomatic aide, who died from the wounds.

When he was taken into custody by French authorities, Herschel, who saw himself as some kind of avenging angel, immediately and then repeatedly told them that he had shot the man, Ernst Vom Rath, in response to the treatment of Polish Jews and, in particular, of his own family.

When he was taken into custody by French authorities, Herschel, who saw himself as some kind of avenging angel, immediately and then repeatedly told them that he had shot the man, Ernst Vom Rath, in response to the treatment of Polish Jews and, in particular, of his own family.

The Nazis reacted to the murder with the carefully staged mob rampage that destroyed Jewish businesses and synagogues and terrorized Jewish people throughout Germany and Austria on the night of November 9 and 10, 1938 — the so-called Kristallnacht.

Meanwhile, Hitler and his partners in paranoia had a different take on the crime. They saw it as the work of the “international Jewish conspiracy” that actually existed only in their nightmares. Hitler sent representatives to both observe, manipulate, and exploit the proceedings against Herschel.

Before the case was played out, however, Germany invaded France, and after Herschel, with the connivance of the French, dodged the grasp of the Nazis in a chain of events that sounds like a Marx Brothers scene, he fell into German control.

Hitler, employing a brand of logic of which only he was capable, decided to stage a show trial so that the international community would conclude from this solitary crime that Jews everywhere were plotting to take control of Germany if not the whole world.

Hitler, employing a brand of logic of which only he was capable, decided to stage a show trial so that the international community would conclude from this solitary crime that Jews everywhere were plotting to take control of Germany if not the whole world.

Kirsch describes the elaborate investigations and other preparations the Nazis made for this spectacle, inquiring into the most remote details of Herschel’s background.

But Hitler didn’t know whom he was up against. The hundred-pound dropout pulled the rug out from under the Nazi propaganda machinery by telling interrogators that he and Vom Rath had actually been involved in a homosexual relationship that went sour. It was a idea that had been suggested to him by one of his lawyers while he was still in French custody. The Nazis were stymied. Given Hitler’s horror of homosexuality, they couldn’t let the show trial go ahead and take a chance that Herschel’s claim would become public. On the other hand, they also couldn’t simply do away with Herschel after making such a big deal about how the case would be tried in public. The trial was postponed — indefinitely, as it turned out.

In a way, that’s where this story ends. No one knows what became of Herschel Grynszpan, although the debate goes on about whether he was a megalomaniac lone ranger or an overlooked hero of the Jewish resistence.

It’s a wonderful yarn, and Kirsch tells it like a novelist, exploring the psyche of an oddball teenager who played a quirky role in the biggest historic epoch of the twentieth century.