Books: “Explosion at Morgan”

March 28, 2013

Residents of South Amboy leave the city on foot as fires and explosions rock the Gillespie shell-loading plant.

During the four decades I spent covering the news of Central New Jersey, there were sporadic stories about artillery shells being unearthed up and down the coast in Middlesex and Monmouth counties. These were the lingering legacy of a catastrophe that occurred in 1918, an event described in Explosion at Morgan: The World War I Middlesex Munitions Disaster by Randall Gabrielan. The title refers to a series of fires and explosions at the T.A. Gillespie Loading Co., a shell-loading operation, on October 4 and 5, 1918 — just a few weeks before the end of World War I.

The plant, which was located in the Morgan section of Sayreville, was one of four identical facilities hastily built in New Jersey to supply the firepower needed by the allied armies in Europe. Operations at the plant were overseen by U.S. government inspectors

The loading of shells required the handling and processing of huge amounts of TNT and ammonium nitrate, which were combined and heated to produce amatol, a highly explosive material. There is no certainty as to what sparked the calamity, but Gabrielan writes that the first explosion probably occurred in a kettle in which 2,600 pounds of amatol was being brewed.

Once the trouble started, it spread into chaos, with fires raging and shells flying in all directions. The concussions caused property damage over a wide area surrounding the plant, but particularly in the City of South Amboy, where virtually every window was broken. People started fleeing the city simply out of fright, but eventually authorities ordered an evacuation. There were at least 100 people killed in the plant, although the actual total is not known because some of the victims were vaporized in the explosions. Gabrielan also reports that there were about 150 injuries.

This book is carefully researched and precisely written, and its value is not only in its reconstruction of the Gillespie disaster, but in putting both the Gillespie plant itself and the explosions in the wider context of the history of that time. Gabrielan points out that, despite the occasional recovery of a shell, the dramatic and destructive incident has largely faded from the collective memory of the community that was affected by it.

Books: “Words from the White House”

March 20, 2013

When we were watching episodes of Downton Abbey on a DVD, we turned on the English subtitles, because we had trouble understanding a couple of the actors — particularly Rob James-Collier as Thomas Barrow and Sophie McShera as Daisy Mason.

It turned out that while some of our difficulty with the dialogue had to do with the one actor’s mumbling and the other one’s accent, some of it also had to do with the vocabulary itself — British terms that we did not know.

Most of us are familiar with terms like “lorry,” “loo,” and “lift,” but we saw others in the captions that we had never heard before.

It was to be expected that the English used in Britain and the English used in the United States would evolve differently, but I learned recently that that didn’t happen only over time but was done deliberately, on our side of the ocean, soon after the American Revolution.

That’s what Paul Dickson reports in his book Words from the White House, which is a compilation of words and phrases that either were either coined or made popular by presidents and other prominent Americans.

According to Dickson, an 18th century sentiment shared by Thomas Jefferson and Noah Webster, was that Americans had to craft for themselves a language that was distinct from the “king’s English.”

Webster was so confident that this goal could be achieved that he wrote in 1806 that “In fifty years from this time, the American-English will be spoken by more people than all the other dialects of the language.”

Part of the process by which language evolves is “neologizing” — that is, inventing words or phrases from whole cloth.

Dickson writes that the word “neologize” was itself neologized by Jefferson in 1813 in a letter to John Adams.

So Theodore Roosevelt, who — for my money — is disproportionately represented in this book, was neologizing when he invented the term “pussyfooter,” and his distant cousin FDR was doing the same when he created the useful word “iffy.”

Some presidents have been accused of using non-standard terms, not because they were being inventive but because they didn’t know any better.

In this regard, for instance, Dickson mentions Warren G. Harding and George W. Bush.

Harding has often been ridiculed for his 1920 campaign promise of a “return to normalcy,” but Dickson points out that the word “normalcy” had been already in use in several fields, including mathematics.

Harding’s innovation was to give the term a political meaning — and, the author reminds us, it worked.

The second Bush — who could be hard on English — was kidded mercilessly for his used of the term “decider” which he applied to himself when the press asked him about calls for the resignation of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld (“I’m the decider, and I decide what’s best.”) Dickson gives Bush credit for coining this word, but apparently the author didn’t check a dictionary: that word was around before George Bush was president, meaning exactly what he used it to mean.

Books: “Emancipation Proclamation”

March 12, 2013

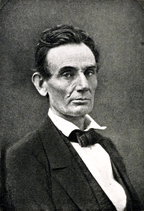

The recent movie Lincoln is serving an important function if it adds some balance to the public perception of the 16th president. No film that I have seen has presented Abraham Lincoln in such realistic terms, and the decision to focus on his campaign to get the 13th Amendment enacted was inspired, because that aspect of Lincoln’s presidency is not well known.

The recent movie Lincoln is serving an important function if it adds some balance to the public perception of the 16th president. No film that I have seen has presented Abraham Lincoln in such realistic terms, and the decision to focus on his campaign to get the 13th Amendment enacted was inspired, because that aspect of Lincoln’s presidency is not well known.

In a way, Lincoln is a victim of his own success. Under his watch, the Union was preserved and human slavery was outlawed in the United States. As a result, Lincoln is enshrined in the national memory as a miracle worker, a savior, almost super human. The apotheosis began almost the moment the public learned of his death.

Among the titles applied to Lincoln is “great emancipator,” but the sobriquet doesn’t reflect Lincoln’s internal struggle and his political struggle over the notion that the federal government should free the millions of people who were being held in bondage in the South when the Civil War erupted.

In Emancipation Proclamation: Lincoln and the Dawn of Liberty, Tonya Bolden spells out the hazardous route Lincoln traveled to his decision to issue the document that fixed his image in history.

In Emancipation Proclamation: Lincoln and the Dawn of Liberty, Tonya Bolden spells out the hazardous route Lincoln traveled to his decision to issue the document that fixed his image in history.

The book is marketed by the publisher, Abrams, as being for young readers but the clear and concise treatment would be serviceable for any adult who wants to catch up on this topic.

Lincoln was progressive for his time. He hated human slavery and would have abolished it if he thought he could. But the relationship between the states and the federal government was still evolving in the mid 19th century, and Lincoln didn’t think Constitution gave the federal government the power to interfere with slavery where it already existed.

Inasmuch as the Civil War erupted shortly after and largely because of Lincoln’s first inauguration,he was preoccupied with one thing, and that was saving the Union. He said in so many words that whatever he did about slavery — abolish it, modify it, leave it alone — he would do only because it would save the Union. In the end, he was true to his word, because the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared free only those people who were being held as slaves in states or parts of states in rebellion against the federal government, was a war measure. Lincoln reasoned that he could take that action as commander in chief even if he couldn’t have taken it as a peacetime president. Even then, he hesitated.

Inasmuch as the Civil War erupted shortly after and largely because of Lincoln’s first inauguration,he was preoccupied with one thing, and that was saving the Union. He said in so many words that whatever he did about slavery — abolish it, modify it, leave it alone — he would do only because it would save the Union. In the end, he was true to his word, because the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared free only those people who were being held as slaves in states or parts of states in rebellion against the federal government, was a war measure. Lincoln reasoned that he could take that action as commander in chief even if he couldn’t have taken it as a peacetime president. Even then, he hesitated.

While Lincoln was considering the advisability of freeing slaves as a way of weakening the southern economy, he had to take into account the potential reaction of the border states — slave states that hadn’t left the Union — as well as the reactions of white Union soldiers who were willing to fight to save the Union but not to free black slaves. Meanwhile, he was under pressure from the swelling abolitionist movement to simply put an end to slavery in one sweeping gesture.

Lincoln also gave a lot of thought to what would become of the slaves once they were emancipated, and his thoughts were shaped by the fact that he didn’t believe in the equality of the black and white races and didn’t think black and white people could live together in peace. Accordingly, his solution was to colonize the freed slaves, preferably in South America or West Africa, even though most slaves at that time had been born in the United States. But by February 1865, Lincoln was publicly endorsing voting rights for at last some educated black men.

This is an attractive book — an art book, really — richly illustrated with images from the period and embellished with break-out quotes from prominent men and women with an interest in the subject of emancipation.

Neflix Update No. 76: “The Long Walk Home”

February 22, 2013

I am in the process of reviewing a new book about the Emacipation Proclamation.

I am in the process of reviewing a new book about the Emacipation Proclamation.

The book is heavily illustrated, and some of the pictures are photographs of people who were held in slavery in this country. I often pause over pictures like that, studying the faces. The faces remind me of the painful fact that epochs such as American slavery, Jim Crow, and the Holocaust were about the injustice and pain inflicted on individual men, women, and children.

The 1990 film The Long Walk Home makes that point with a sharp impact. The story, originally written by John Cork when he was a student at the University of Southern California, is set in Montgomery, Alabama, during the bus boycott of 1955-1956. That was the seminal protest against racial discrimination on the city’s transit system, sparked by the arrest of Rosa Parks for refusing to surrender her seat to a white man. The stand taken by Rosa Parks inspired a boycott of the bus system by black citizens of Montgomery and eventually led to a ruling by the U.S. Supreme court that the racially discriminatory laws in Montgomery were unconstitutional and must be vacated.

The cast of The Long Walk Home includes Whoopie Goldberg as Odessa Carter, a maid employed by Miriam Thompson, played by Sissy Spacek.

Miriam Thompson is affected by the boycott, because Odessa won’t ride the bus, and the long walk, besides being grueling, makes her late for work each morning. Miriam’s partial solution to that is to pick up Odessa two mornings a week, a decision that Miriam’s husband, Norman (Dwight Schultz), goaded by his redneck brother, Tunker (Dylan Baker), vehemently objects to. The growing tension in the Thompson family over this issue, and her observation of Odessa’s ordeal, lead Miriam to re-examine her own values and her place in the roiling civil rights issue in the city.

This is a good movie in many respects, including Whoopi Goldberg’s understated performance as a woman who solemnly decides that she has had enough of being patronized, de-humanized, and humiliated. It’s important that she is portrayed in the midst of her own family, her husband and children. Shifting the point of view to this setting reminds us that racial discrimination didn’t do violence to some abstract principle; it did violence to regular people who were trying to live as human beings and citizens.

Books: “Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man”

December 18, 2012

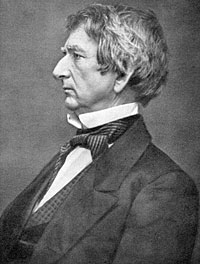

If the Chicago Tribune had it right, William H. Seward was the prince of darkness.

In 1862, when Seward was Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state and the Civil War seemed as likely as not to permanently destroy the federal union, the “world’s greatest newspaper” knew whom to blame. Seward, the Tribune said, was “Lincoln’s evil genius. He has been president de facto, and has kept a sponge saturated with chloroform to Uncle Abe’s nose all the while, except one or two brief spells.” The Boston Commonwealth was about as delicate in its assessment of Seward: “he has a right to be idiotic, undoubtedly, but he has no right to carry his idiocy into the conduct of affairs, and mislead men and nations about ‘ending the war in sixty days.’ ”

This demonic imbecile, as some editors would have it, is the subject of Walter Stahr’s comprehensive and engaging biography, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man. Stahr has a somewhat different take than the Tribune’s Joseph Medill. While Stahr acknowledges that Seward was overly optimistic about prospects for the federal government to prevail over the seceding states, and while he acknowledges that Seward sometimes turned to political chicanery and downright dishonesty, he also regards Seward as second in importance during the Civil War era only to Lincoln himself.

Seward, a former governor of New York and United States Senator, was by Stahr’s account, very close to Lincoln personally, which probably contributed to the rancor directed at Seward from others in the government who wanted the president’s attention. Their relationship was interesting in a way that is analogous to the relationship between Barak Obama and Hillary Clinton in the sense that Seward was Lincoln’s chief rival for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. Seward’s presidential ambitions, which were advanced by fits and starts by the political instigator Thurlow Weed of New York, are well documented in this book. But, as Stahr makes clear, Seward’s disappointment at losing the nomination to Lincoln did not prevent him from agreeing to serve with Lincoln at one of the most difficult periods in the nation’s history nor from serving him loyally.

As important an office as secretary of state is now, it was even more so in the 19th century, because its reach wasn’t confined to foreign affairs. It wasn’t uncommon for the secretary of state to be referred to as “the premier.” At first, Seward’s view of the office might have exceeded even the reality; he seems to have thought at first that he would make and execute policy and Lincoln provide the face of the administration. Lincoln soon made it clear who was in charge, and he and Seward worked well together from then on.

Seward’s service in Lincoln’s administration nearly cost him his life on the night that Lincoln himself was murdered by John Wilkes Booth. One of Booth’s accomplices, Lewis Payne, forced his way into the house where Seward was lying in bed, recovering from injuries he had sustained in a serious carriage accident. Payne, who was a wild man, tore through the place, cutting anyone who tried to stop him, and he attacked Seward, slashing his face. Payne fled the house — he eventually hanged for his crime — and Seward survived.

After the double trauma of Lincoln’s death and Seward’s own ordeal, it would have been understandable if Seward had withdrawn from public life. Seward wasn’t cut of ordinary cloth, however, and he agreed to remain at his post in the administration of Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson. Johnson was an outstanding American in many respects—he was the only southern member to remain in his U.S. Senate seat after secession, and he gave up the relative safety of the capital and took his life in his hands when Lincoln asked him to serve as military governor of Tennessee — but he was not suited for the role that was thrust on him by Booth.

Stahr explores the question of why Seward stayed on during the troubled years of Johnson’s tenure. He infers, for one thing, that Seward agreed with Johnson’s idea that the southern states should be quickly restored to their place in the Union without the tests that the Republican majority in Congress, and especially the “radical” wing of the party, wanted to impose. Stahr also writes that Seward believed that if Congress succeeded in removing Johnson on impeachment charges that were politically motivated it would upset the balance of power in the federal government for decades to come.

I mentioned Seward to a co-worker today, and she said, “of the folly?” She was referring to the purchase of Alaska, which Seward completed during Johnson’s administration. Stahr writes that much of the press supported the purchase of “Russian American” at first, and although the term “folly” was tossed about later, prompted in part by Seward’s further ambitions for expansion, the epithet was never widely used.

Alaska was only one of Seward’s achievements. He was a skillful diplomat who was equipped to play the dangerous game that kept Britain and France from recognizing the Confederate States of America. Although he may have underestimated the threat of secession and the prospects for a protracted war, he was at Lincoln’s side every step of the way—playing a direct role, for instance, in the suspension of habeas corpus and the incarceration of suspected spies without trial. He was not an abolitionist—and in that respect he disagreed with his outspoken wife, Frances— but Seward was passionate about preventing the spread of slavery into the western territories. He believed that black Americans should be educated. He did not support fugitive slave laws and even illegally sheltered runaway slaves in his home in Auburn, N.Y.

Seward was a complicated character who stuck to high moral and ethical standards much of the time, but was capable of chicanery, deceit, and maybe even bribery if it would advance what he thought was a worthy purpose.

A world traveler, he was one of Washington’s leading hosts, known for his engaging manner, and yet with his omnipresent cigar and well-worn clothes he appeared to all the world as something akin to an unmade bed. Henry Adams, who admired Seward, described him as “the old fellow with his big nose and his wire hair and grizzled eyebrows and miserable dress” who nevertheless was “rolling out his grand, broad ideas that would inspire a cow with statesmanship if she understood our language.”

“The Best of Enemies”

December 2, 2012

During a group discussion in our parish last month, we touched on the question of whether anyone is beyond redemption. We had in mind folks like the terrorists who carry out mass murders and suicide missions for what they perceive to be good or necessary causes. The question might have answered itself if any of us that night had thought of C.P. Ellis. I, for one, had never heard of him.

More recently, I learned about Ellis while I was writing about a play by Mark St. Germain entitled “The Best of Enemies.” The play, in turn, is based on a book by that title, written by Osha Gray Davidson. The enemies were Ellis, who in 1971 was the grand cyclops of a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan in Durham, North Carolina, and Ann Atwater, who was a black civil rights activist in the same city.

Durham was late coming to the school desegregation party, and a community organizer named Bill Riddick arrived in town to get a public dialogue going. He proposed to conduct a series of town meetings, and he chose Atwater and Ellis — who couldn’t stand the sight of each other — as co-chairs. As the process unfolded, the unlikely pair gradually realized that as economically marginalized members of the community, and as parents who were concerned about the quality of their children’s education, they had more in common than they had thought. The experience also inspired Ellis to examine the reasons for his membership in the Klan. Ultimately, Ellis quit the Klan by tearing up his membership card at a public gathering; as a result, he was ostracized by his former friends and threatened with death.

Ellis became a union leader, representing constituencies of mostly black workers. He and Atwater were friends until his death in 2005.

Mark St. Germain’s play was introduced at the Barrington Stage Company in Massachusetts and is currently on stage at the George Street Playhouse in New Brunswick.

You can read Studs Terkel’s interview with Ellis, in which Ellis talks about the reasons for his membership in the Klan and describes his encounter with Ann Atwater, by clicking THIS LINK.

“You’ve got to be taught to hate and fear”

October 23, 2012

Nellie Forbush (Kelli O’Hara) and the navy nurses sing “I’m Gonna Wash that Man Right Outta My Hair” in the Lincoln Center revival of “South Pacific”

On one of our first dates, I took Pat, now my wife, to see a major production of South Pacific, the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. Betsy Palmer played Nellie Forbush and William Chapman played Emile de Becque. Neither of us had ever seen the show on stage, but both of us had seen the 1958 film with Mitzi Gaynor and Rossano Brazzi (with Giorgio Tozzi dubbing Brazzi’s songs), and both of us owned the cast albums from that film and from the original Broadway production with Mary Martin and Ezio Pinza.

The musical play, which first appeared in 1949, was based on James Minchener’s 1947 book, Tales of the South Pacific. This book, which won the Pulitzer Prize, is a collection of loosely connected stories based on Michener’s experiences as a Navy officer on the island of Espiritu Santo. I find it an absorbing book because of its ability to transport the reader into the unique environment of the Pacific Islands during that war.

Rodgers and Hammerstein combined three of Michener’s stories to create the musical play, and they determined to deal with two instances in which romantic liaisons were disrupted by racial prejudice. One of those situations arises when Navy nurse Nellie Forbush, whose previous life experience was confined to Little Rock, Arkansas, falls in love with French planter Emile de Becque but discovers that he had previously lived and had children with a Polynesian woman. For reasons that she herself cannot articulate, Nellie is repulsed by the idea, and she undergoes a wrenching internal struggle.

The other conflict involves a Marine lieutenant, Joe Cable, who falls in love with a Tonkinese girl who is not yet an adult, but refuses to marry the girl because of the color of her skin. In a scene in which De Becque and Cable discuss their contradictory crises, De Becque declares that he does not believe that racial prejudice is inborn, and Cable punctuates that idea with a lyric: “You have to be taught to hate and fear / You have to be taught from year to year / It has to be drummed in your dear little ear / You have to be carefully taught … to hate all the people your relatives hate.”

This lyric brought opprobrium down on Rodgers and Hammerstein from some quarters in the United States. Cable’s song was described as not only indecent, because by implication it encouraged interracial sex and — God forbid! — breeding, but that it was pro-communist because who but a communist would carry egalitarianism so far? Some Georgia politicians actually tried to stifle the song through legislation. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s position was that the song was about what the play was about and that, even if it sank the show, the song would stay.

We saw the recent revival of South Pacific at the Lincoln Center twice, and this past weekend, we had the opportunity to see it again in a production at the non-profit Ritz Theatre in Haddon Township, New Jersey. One of the impediments to mounting this show is that it requires an outstanding cast and company; it can’t be faked. The Ritz was up to that challenge in every respect. In fact, Pat and I agreed that Anabelle Garcia was the best Nellie Forbush we had ever seen.

South Pacific was written shortly after World War II. The original production won a Pulitzer Prize and ten Tony Awards. In fact, sixty-two years later, it is still the only musical to win all four Tony Awards for acting.

What is striking about South Pacific is that although it is necessarily performed entirely in the milieu of the 1940s, it does not get old. Racism is still a serious issue in the United States, and some of the criticism directed at this show for addressing that issue sounds disturbingly like rhetoric we can still hear today.