Books: “Color Blind”

March 27, 2014

One aspect of my father’s life that I don’t know nearly enough about is the time he spent managing a semi-pro baseball team. He mentioned it now and then, but the only detail I have retained is that his team played a couple of games against a team managed by Johnny Vander Meer. Vander Meer is the only pitcher in the history of major league baseball to pitch no-hitters in two consecutive games. That was in 1938. He also pitched a no-hitter in the Texas League 14 years later.

At the time that my father told me about opposing Vander Meer, I didn’t understand the importance of semi-pro baseball. In fact, I probably didn’t know what the expression meant. In broad terms, there have historically been three categories of baseball leagues: professional, semi-professional, and amateur.The professional leagues are what we know as the major and minor leagues, including the minor leagues whose teams are not affiliated with major league teams. Among the rest, a team is considered semi-pro if even one of its players is paid.

How many were paid and how they were paid varied a lot from time to time and place to place. There were teams sponsored by companies, by local businesses, by civic and social organizations, by towns, and by private individuals. On some teams, every player was paid. On some only a handful. And in circumstances in which the competition was intense, one or more of the players on a team who were paid were ringers recruited from the minor leagues or the Negro Leagues with offers of bigger salaries than the pros were paying.

There were semi-pro teams all over the United States and Canada, and many of them could draw crowds in those days when the big leagues were concentrated in the eastern part of the country where they were out of reach for most Americans. Semi-pro ball could provide an especially welcome diversion during the epoch in which the plains were beset by both economic depression and drought. One team in particular is the subject of Tom Dunkel’s book, “Color Blind.” The team Dunkel writes about was based in Bismark, North Dakota in the 1930s; it was not a member of a league, but played against teams in nearby and far-off towns and against barnstorming teams that wandered the landscape trying to make a buck. The Bismark team, so far as we know, didn’t have an official nickname although they are often referred to as the Churchills. That’s a nod to Neil Churchill, a partner in a Bismark auto dealership, an habitual if not addicted gambler, and the owner and frequently the manager of the local nine.

Churchill was devoted to the game and he was competitive. He was constantly striking deals with pro players to give the Bismarks an edge over their opponents. Winning was such a priority with him that he didn’t care what color the players were. In fact, because the pro leagues were more than a decade away from coming to their senses, Churchill was able to attract some talented black players, including Satchel Paige. Paige should have spent his career in the majors, but because of the color line and because of his wanderlust, he’d take the field wherever he got the best offer. In 1933 and in 1935, that offer — a $400 a month and a late-model car—came from Churchill , and Paige bolted from the Negro League team in Pittsburgh and made for Bismark. That was no small achievement for Churchill. Although there is no way to establish the widely held belief that Paige was the greatest pitcher of his time, and perhaps of any time, we know enough about him to know that he was extraordinary. In ’35 he started and won four games and relieved in another when Bismark took seven straight to win the inaugural National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita.

Among the other outstanding black players Churchill recruited were pitcher-catcher Ted “Double Duty” Radcliff, and catcher Quincy Thomas Trouppe (nee Troupe) who, by the way, was the father of prominent poet-journalist-academic Quincy Thomas Troupe Jr.

Churchill led the only integrated organized team in that rough-and-tumble era in baseball, and he got some pushback for his trouble. And Bismark’s black players, of course, had to endure the insults and isolation that the land of “all men are created equal” imposed on many of its citizens then and for more than 30 years after. In his book, Dunkel brings to light a fragment of American history in which the relationship between the people and their national game was much more intimate than it was to become, and by evoking the names of men like Paige and Radcliffe and Trouppe, he reminds us of the crime that was committed for more than six decades against many of its finest practitioners.

Don’t let the bedbugs bite

December 19, 2013

Every year at this time, and during the run-up to Valentine’s Day, the public-radio station I listen to runs sponsorship announcements from an outfit known as Pajamagram. Their deal is that you can contact them and have pajamas delivered to someone in the same manner in which you might send flowers if flowers didn’t require a second mortgage. I’ve being hearing these seasonal announcements for years, but today for the first time the information that Pajamagram can provide footie pjs reminded me of a name I haven’t thought of in decades: Dr. Denton. When I was a kid, “Dr. Denton” was a euphemism for pajamas with feet. My brother and I wore them, and that’s what we called them. These “blanket sleepers,” as they were more formally known, were manufactured by the Dr. Denton Sleeping Garment Mills of Centreville, Michigan. The company was founded in 1865 as the Michigan Central Woolen Company and operated through the first half of the twentieth century.

It wasn’t just in our household that footed pajamas were called Dr. Dentons. In fact, the usage was so common that the brand name became the generic term for the garment, what is technically known as a “genericized trade mark.” The design was patented by Whitley Denton, an employee of Michigan Central. His patent application emphasized that the garment, including the feet but sans the soles and arms, would be made in one piece with a minimum of cutting and stitching and seams, rendering the sleepers more economical to manufacture and more comfortable for wearers. Like the classic “union suit” the sleeper had a “trap door” in back so the user could go to the bathroom without having to disrobe.

You can see Denton’s patent application, including the drawings of the original design, by clicking HERE. Denton took on the honorary doctorate, at least for purposes of the brand name, to create the impression that there was some medical wisdom behind the pajamas. Although the original manufacturer is gone, other companies have used the trade mark, including Simplicity, which for a while was selling Dr. Denton patterns to what I imagine was a limited market.

“. . . or the highway.”

October 9, 2013

The standoff between President Obama and the Republican majority in the House calls to my mind the struggle between President Andrew Johnson and the Republican majority after the Civil War and the murder of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a fine man in many respects, but if ever there was a wrong man at the wrong time in the presidency it was he. Johnson, who was from Tennessee, was the only U.S. senator who remained in his seat when his state seceded from the Union. He was elected vice president in 1864 on a fusion ticket with Lincoln and was vaulted into the presidency by Lincoln’s death. The Republicans were the progressive party at the time and the Democrats were not only conservative but identified with the slave-holding South. Johnson himself owned a few household slaves, although one of his daughters remarked that it was difficult sometimes to tell who was slave and who was master. Millions of words have been written about this, but suffice it to say that Johnson and the Republicans disagreed about how the former Confederates states and the former slaves should be treated by the federal government. As that dispute was boiling over, Congress passed a routine bill to fund the Army but attached an unrelated rider — which came to be known as the Tenure of Office Act — which provided that once the president had appointed a federal official with the consent of the Senate, he could not remove the official from office without the consent of the Senate.

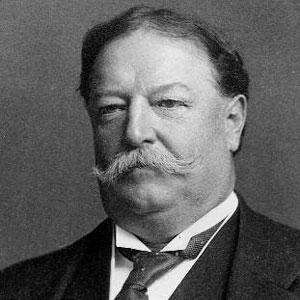

Johnson believed that the Tenure of Office Act was an unconstitutional incursion on the powers of the president, but he wasn’t prepared to squelch it by vetoing the army appropriations bill. So he signed it, but afterward he deliberately violated it by removing from office Edwin M. Stanton, the secretary of war, who had served in the Lincoln administration in that role and as attorney-general. Because of vague wording in the law, it’s an open question whether Johnson had violated it at all. However, Stanton refused to leave, which led to a chain of events, including Stanton barricading himself in his office, that descended to the level of comic opera. Johnson’s presumed violation of the Tenure of Office Act was the centerpiece of the impeachment proceedings the Republicans brought against him. Johnson was acquitted and completed his term, but the balance of power between the executive and Congress had been disrupted. Congress repealed the Tenure of Office Act in 1887, and the U.S. Supreme Court, ruling on a similar law in 1926, said in an opinion written by Chief Justice and former President William Howard Taft, that the Tenure of Office act had been invalid.

Netflix Update No. 81: “Sally of the Sawdust”

October 1, 2013

Watching silent movies always gives me a melancholy feeling. I think the sensation comes from a wistful and naive attraction to the era in which those films were made — an era that was gone long before I was born. The mood comes over me almost regardless of the film I’m watching, whether it is drama or comedy.

Watching silent movies always gives me a melancholy feeling. I think the sensation comes from a wistful and naive attraction to the era in which those films were made — an era that was gone long before I was born. The mood comes over me almost regardless of the film I’m watching, whether it is drama or comedy.

And so it was with a mixed response that I watched D.W. Griffith’s 1925 comedy Sally of the Sawdust, in which the leading players were W.C. Fields, Carol Dempster, and Alfred Lunt. This film, which is based on Poppy, a 1923 stage musical, is lighter fare than usually comes to mind when Griffith’s name is mentioned, but it has dark undertones as well.

Fields plays “Professor” Eustace McGargle, a circus juggler and con man who befriends a single mother and her daughter, Sally (Dempster). After the mother dies, McGargle briefly considers returning Sally to her grandparents in the fictional New York suburb of Green Meadows, but he has a genuine affection for the child and decides to keep her with him.

As Sally grows, McGargle also uses her as a dancing warm-up to his own act. When their fortunes are at a low ebb, the pair wind up in Green Meadow where they work at a charity carnival while McGargle prepares to finally restore the girl to her family, who have have benefitted financially from a real estate boom in the area. Although the handsome son (Lunt) of a local tycoon falls in love with Sally, his father is repelled by the idea of such a match and does what he can to prevent it by having McGargle and Sally arrested on the basis of the professor’s three-card monte operation. There are parallel frenetic scenes as Sally attempts to escape from custody and McGargle purloins a tin lizzy and leads a gang of bootleggers on a wild chase as he attempts to reach town and his distressed ward. To make a long story short, they all live happily ever after.

One impression I couldn’t shake is that this film, which appeared toward the end of Griffith’s career, was longer than it had to be. The story is thin and obvious, and the twin sequences of Sally’s escape and McGargle’s chase, go on too long by about a third.

Still, it was interesting to watch Fields, who in his later career made so much of verbal comedy, perform for an hour and a half in silence. Also, McGargle foreshadows other roles Fields would play but, except for Wilkins Macawber in David Copperfield, his characters didn’t face situations quite as grave as the one McGargle wrestled with. Fields would get to reprise this role in Poppy, a 1936 sound version of the same story.

I found Carol Dempster to be very appealing as Sally. She was one of Griffith’s discoveries and appeared in many of his films, and she was also for a time his lover. While I was watching Sally in the Sawdust, my wife came into the room and remarked that Dempster was kind of forlorn-looking. That struck me, too, and I read that Dempster attracted critical remarks on that account at the time she was making these movies. But I found that slightly hangdog quality both suitable and, in its own way, attractive. Evidently, at least some film critics now feel the same way.

A significant factor in my enjoyment of this film was the score that was written and performed, on a digital piano, by Donald Sosin.

I’m going to watch this film again and use the pause button several times. As with most silent films that were shot on locations, I often found myself transfixed by the background, by the storefronts and the signs and the cars and the structures that were serving their purpose on a long-ago day when Griffith’s camera happened to capture them.

Daddy’s little girl

September 4, 2013

My wife, Pat, who is reading Adriana Trigiani’s novel The Shoemaker’s Wife, has mentioned two characters in the story who are familiar to me: Enrico Caruso and Geraldine Farrar. We like to say, even though it can’t be demonstrated, that Caruso was the nonpareil of tenors, and Farrar, his contemporary, was a popular soprano and film actress. She was a member of the Metropolitan Opera Company for 17 years, singing 29 roles in some 500 performances, frequently appearing with Caruso. She had a particular following among young women, and they were known at the time as “Gerryflappers.” I was young when I became a fan of hers, too, but that was nearly 30 years after she had retired as a singer. A kid of eclectic tastes, when I came home from the record store on most Friday nights, I could be carrying doo-wop, country-and-western, American standards, or opera. I bought many discs with cuts by Caruso, Farrar, or the two of them together.

A biographical detail about Farrar that particularly appeals to me is the fact that her father, Sidney, was a major league baseball player from 1883 to 1890. A first baseman, he played most of his career for the Philadelphia National League franchise. In his last season, he bolted to the maverick Players League, still playing in Philadelphia. He appeared in 943 games and, in the dead-ball era, had 905 hits and a .253 batting average.

When Sid Farrar was through playing baseball, he opened a men’s clothing shop in Melrose, Massachusetts, in partnership with Frank G. Selee, a Hall of Fame major league manager. Farrar and his wife, Etta, were singers in their own right. Farrar was a baritone, and it was said of him that if he was speaking in what, for him, was a conversational tone of voice on one side of a street, he could be clearly heard from the other side.

When Geraldine went to Europe to study voice, her parents went with her and remained on the Other Side until Geraldine had made a name for herself in Berlin, Munich, Salsburg, Paris, and Stockholm and returned to the United States in 1906.

In later life, when he had been widowed, Sid Farrar was a familiar figure at Geraldine’s concerts, and she said that he was often surrounded by other old ballplayers who may have looked a little out of place in the classical concert hall. It dawned on her, she said, that those old guys weren’t there to see her; they were there to see her dad.

One of my favorite Caruso-Farrar recordings is their 1912 rendition of “O Soave Fanciulla” from La Boheme. Click HERE to hear it.

Books: “The Art of Controversy”

June 18, 2013

It’s one of the ironies of 19th century history that the same man who gave us the roly-poly image of Santa Claus that warms our hearts every year was also one of the most damaging political cartoonists of his era. But that’s the way it was with Thomas Nast, one of the artists Victor N. Navasky discusses in The Art of Controversy, a meditation on the art and implications of the caricature.

Nast famously set his sights on Tammany Hall, as the Democratic Party machine in New York City was known, and particularly on William M. “Boss” Tweed, a businessman and politician who dominated the affairs of the city largely through his control of patronage in the form of both contracts and jobs.

As Navasky relates, Nast’s work in Harper’s Weekly during the 1871 election campaign is credited with purging city government of the Tammany gang. Tweed and others in his circle were subsequently charged with enormous thefts of public funds and sentenced to prison. Tweed tried to flee, but a Spanish customs official arrested him after recognizing him from Nast’s caricatures.

Tweed was no stranger to criticism, but he famously remarked about Nast’s assaults on him: “Stop them damn pictures! I don’t care a straw for your newspaper articles. My constituents can’t read. But they can’t help seeing them damn pictures!”

The story of Nast and Tweed illustrates many of the points made by Navasky, who is the former editor and publisher of The Nation and a former editor at The New York Times Magazine. One of those points is the power of caricature, which is a form of cartooning that emphasizes or exaggerates distinctive physical characteristics of the subject: Richard Nixon’s ski nose and widow’s peak, for example, or Lyndon Johnson’s ears.

This is neither a technical analysis nor a history, although Navasky reaches back a few centuries in discussing the origins of caricature, noting that Leonardo da Vinci may have originated the form in the 16th century and William Hogarth was one of those who had perfected it in the 18th. This book is more a matter of Navasky thinking through the subject of political cartoons and not necessarily answering all of his own questions about the topic.

The author writes a lot about what makes caricature so effective. How effective? He points out one case in which an artist’s work landed him on Adolf Hitler’s “death list” and another case in which a cartoonist for Arab daily newspapers in Europe and the Near East was assassinated. In a far different vein, he devotes a chapter to the Nazi periodical Die Stürmer, which conducted a relentless campaign to ridicule and demean Jews, with caricature as a principal method. The editor, Julius Streicher, was hanged after the Nuremberg trials, and the cover cartoonist, Philipp Rupprecht, was sentenced to six years in prison, a sentence Navasky thinks was too light.

This potency raises in Navasky’s mind the question of whether political cartooning should enjoy exactly the free-speech protection that the written word has in the United States. He isn’t arguing that it shouldn’t, but he explores significant ways in which the two forms of expression are not identical — including the lasting (and frequently negative) impression a caricature makes and the fact that one can answer words with words (as in a letter to the editor), but can hardly make an effective response to a cartoon.

Navasky writes about editorial decisions (to publish or not to publish) such as the “Danish Muhammads” and a case of his own in which practically his whole staff opposed his choice to print a cartoon that portrayed Henry Kissinger “screwing the world.” This is a provocative book from Alfred A. Knopf about the use of caricature at various times in history and in various parts of the world. I screened editorial cartoons for my newspapers for the better part of four decades, but Navasky’s musings have given me new insights and raised questions that I had never considered.

Books: “The Girls of Atomic City”

May 30, 2013

Franklin Roosevelt was good at many things. For one, he could keep a secret. Of course, he was in on the Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb, but he kept what he knew sub sigillo. The urgency of the project was based on the concern that Nazi Germany would build such a weapon first and was known to be trying very hard to find out what kind of research and development was going on in the United States.

Franklin Roosevelt was good at many things. For one, he could keep a secret. Of course, he was in on the Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb, but he kept what he knew sub sigillo. The urgency of the project was based on the concern that Nazi Germany would build such a weapon first and was known to be trying very hard to find out what kind of research and development was going on in the United States.

So Roosevelt kept his counsel — in fact, he kept it to a fault. Although he was aware of his own fragile health, he never said a word to Harry S Truman, his vice president. Truman found out about the project only after Roosevelt’s sudden death in 1945.

If nothing else, Roosevelt’s secrecy set an example for the subjects of Denise Kiernan’s enlightening and witty book, The Girls of Atomic City. These were the young women who were among tens of thousands of Americans recruited to work at the Clinton Engineering Works outside of Knoxville, Tennessee, one of several sites that housed the operations that led to the bomb that would be deployed against Japan.

CEW consisted of four plants — one of which was the largest building in the world — that were built on a massive tract of land the government more or less appropriated, muscling out the farmers and others for whom the area had been both home and livelihood. Along with the plants, the government and its contractors built a sort of town, Oak Ridge, to serve as the residential community for CEW workers, both civilian and military. Some of the employees also lived outside the plant and commuted.

CEW consisted of four plants — one of which was the largest building in the world — that were built on a massive tract of land the government more or less appropriated, muscling out the farmers and others for whom the area had been both home and livelihood. Along with the plants, the government and its contractors built a sort of town, Oak Ridge, to serve as the residential community for CEW workers, both civilian and military. Some of the employees also lived outside the plant and commuted.

CEW had one goal: to enrich uranium to the point that it could be used as the fuel for the atomic bomb being developed by scientists at other sites in the country, most notably Los Alamos, New Mexico. None of the tens of thousands of men and women who worked at the plant knew what was taking place there, except that it was a project designed to win the war. They didn’t know they were refining uranium; they never heard uranium mentioned. Each person was directed to perform the task to which he or she was best suited, but was not told the purpose of the task. Some folks spent their days or nights monitoring gauges and recording the readings; some folks inspected pipes for leaks; some did mathematical calculations; some repeated chemical experiments — the same ones over and over again. Some worked at jobs not directly related to the core purpose of CEW — secretaries, nurses, shopkeepers, custodians.

Everyone was told, repeatedly and forcefully, not to ask questions about what took place at CEW and not to discuss with each other or anyone else any aspect of work at the plant. Employees knew that they were being watched all the time by official personnel and by fellow workers who had been recruited as internal spies. And employees who noticed that someone suddenly vanished from a work site knew that person had probably been overheard speaking out of line and had been jettisoned from the complex with a stern warning to keep quiet.

It was only after the bomb had been deployed against Hiroshima in August 1945, causing unprecedented casualties and property damage, that the workers learned the truth about CEW and about what they had unwittingly made possible. As Denise Kiernan skillfully reports, there was a mixed reaction, a combination of relief, elation, remorse, and foreboding. People were glad that the war would finally end, but many were deeply shaken by the carnage in Japan and worried about what new force had been unleashed in the world.

As the title suggests, Kiernan is especially interested in the young women, including several specific ones, who left home, in some cases along with their families, to work at CEW. Some sought better pay, some sought any kind of work, some were motivated by a yen for adventure. At Oak Ridge, they found what in many ways was a spartan existence, a town without sidewalks but with plenty of ankle-deep mud. Many also found friendship and even romance and, if they were black, the same Jim Crow restrictions on their lives that they had experienced back home. While she tells the story of Oak Ridge and CEW, Kiernan simultaneously traces the development from theory to experiment to technology of nuclear fission, the principal that led to the bomb, and she calls particular attention to female scientists who played significant if under-appreciated roles in that process.

As the title suggests, Kiernan is especially interested in the young women, including several specific ones, who left home, in some cases along with their families, to work at CEW. Some sought better pay, some sought any kind of work, some were motivated by a yen for adventure. At Oak Ridge, they found what in many ways was a spartan existence, a town without sidewalks but with plenty of ankle-deep mud. Many also found friendship and even romance and, if they were black, the same Jim Crow restrictions on their lives that they had experienced back home. While she tells the story of Oak Ridge and CEW, Kiernan simultaneously traces the development from theory to experiment to technology of nuclear fission, the principal that led to the bomb, and she calls particular attention to female scientists who played significant if under-appreciated roles in that process.

Books: “The Slaves’ Gamble”

May 9, 2013

Perhaps I just wasn’t paying attention, but my impression is that the War of 1812 didn’t get much air time when I was in elementary and high school. Where American history was concerned, as I recall, it was all about the Revolution and the Civil War. It took me a while to catch up; it was relatively recently that I caught on that the War of 1812 was, in effect, a continuation of the Revolution.

Among the things I didn’t know about the war was that black men, free and slave, fought on both the American and British sides and also on behalf of the Spanish authorities who were futilely trying to hang onto the Florida territories. Gene Allen Smith, a history professor at Texas Christian University, covers that in detail in his book The Slaves’ Gamble: Choosing Sides in the War of 1812.

An important aspect of this story is that the British, strapped for resources because their government was fighting what turned out to be the decisive war with Napoleon Bonaparte in Europe, encouraged American slaves to bolt from their masters and either emigrate to a British possession — notably Nova Scotia — or enlist in military service. Either way, the British promised the slaves their freedom.

Besides filling their ranks, the British saw this strategy as a means of undermining the Southern economy. The number of slaves who took advantage of the opportunity was slight compared to the million-plus who were in bondage at that time, but the fact that the British were welcoming slaves sent shock waves through the South, where white people always feared a slave rebellion.

Although this is a story about a war fought on many fronts over three years, Smith puts a human face on it by providing anecotes about particular black men who played a part in the epoch.

One example was George Roberts, a free Marylander who served during the war on numerous American privateers — private vessels that harassed and even seized British shipping on the U.S. government’s behalf. Another was Jordan B. Noble, who was born a mixed-race slave in 1800 and joined the 7th U.S. Regiment as a drummer in 1813. He served in the Battle of New Orleans and later took part in the Mexican, Seminole, and Civil wars.

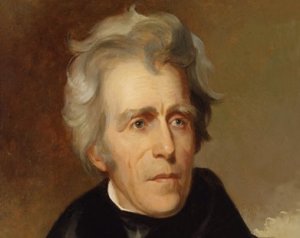

A sad if not surprising episode in this history concerned Andrew Jackson, who recruited slaves to help in protecting New Orleans from a British attack. Jackson promised to free the slaves in return for their service, but, Smith writes, never intended to do so. Jackson, according to the author, “committed them to his cause rather than permitting them to assist the British, and this tied them to the United States.”

Allen explains that, once the war was over, the impact of the British strategy had the unintended effect of strengthening the plantation system in the South and opening new territory — namely, what had been the Spanish Floridas—to slavery. In general, the competence and bravery black soldiers and sailors contributed to the American cause during the War of 1812 was not adequately rewarded. On the contrary, some of the worst experiences for black people in the United States were yet to come.

Book: “Grand Central”

April 19, 2013

Yes, I’ve been around long enough to remember when televisions were not yet a consumer item and radio was the principle source of home entertainment. One of the programs my mother listened to was Grand Central Station, a popular show that ran from 1937 to 1954. This wasn’t a soap opera like Our Gal Sunday, The Romance of Helen Trent, or The Edge of Night, which mom also listened to.

Yes, I’ve been around long enough to remember when televisions were not yet a consumer item and radio was the principle source of home entertainment. One of the programs my mother listened to was Grand Central Station, a popular show that ran from 1937 to 1954. This wasn’t a soap opera like Our Gal Sunday, The Romance of Helen Trent, or The Edge of Night, which mom also listened to.

Grand Central Station was a series of disconnected stories — drama, romance, comedy — all of which, of course, played out at least in part in the railroad station of the title. The announcer who introduced each show described Grand Central as “the crossroads of a million private lives, a gigantic stage on which are played a thousand dramas daily.”

But, as Sam Roberts points out in his book, Grand Central, there was no such thing as Grand Central Station when that show was on the air. By then, the original structure, which was called by that name for a time, had been displaced by Grand Central Terminal, the one that now stands at East 42nd Street and Park Avenue.

The difference is that trains originate and end at a terminal; they don’t pass through. When the first rail facility was built in that location in 1871, it was known as Grand Central Depot. That place wasn’t up to the job to begin with, and after a clumsy expansion project at the turn of the 20th century, it was known for a couple of years as Grand Central Station. But a fatal train accident in 1902 prompted railroad officials to tear down the station and start over again, and the result was the monumental terminal that is now the centerpiece of midtown Manhattan. The complex took ten years to build; it occupies 17 acres.

By the 1970s, both midtown and the terminal had substantially deteriorated, Grand Central reduced to a sanctuary for homeless New Yorkers and a pest hole for commuters to get in and out of as quickly as possible. The terminal wasn’t paying for itself, and there was talk of demolition. Enter some folks with a little more vision — including, not insignificantly, Jacqueline Onassis — and Grand Central was in for restoration instead.

This book, which was published to coincide with the 100th anniversary of Grand Central Terminal, is an elegant volume loaded with photographs to embellish Roberts’ witty and vivid writing. Through the story of Grand Central, we learn about the evolution of rail travel in and out of, and within, the New York metropolis, and about the development of midtown — development, and re-development, for which Roberts writes, Grand Central has been the principal catalyst. It’s also a story of people: robber barons, politicians, engineers, and presidents, but most importantly it’s about the millions and millions of people who have passed through the terminal in haste, in sorrow, in joy, in confusion, and in fear. New York likes to call Times Square “the crossroads of the world,” but in a more literal sense, that title might belong to Grand Central.

You can hear an episode of Grand Central Station at this link.