Touch ’em all, Mr. Freese!

October 28, 2011

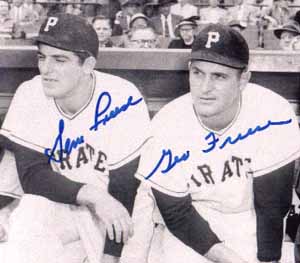

All the excitement about David Freese and his World Series heroics has got me thinking about George and Gene Freese, who were also major league baseball players, though no relatives of David, as far as I can tell. Gene and George were brothers, but they were not the Deans, the DiMaggios, or the Alous. I remember them because they played in the 1950s and 1960s, when I was still reasonably alert, and because I have the kind of mind that retains things such as the names of obscure baseball players.

George Freese appeared in only 61 major league games — “only” being a relative term inasmuch as most of us don’t appear in any — but he hung around the game longer than that as a coach, minor league manager, and scout. I might have remembered him anyway just because he was Gene Freese’s brother, but George has a distinction of his own: he is one of I guess a couple of hundred players who have hit inside-the-park grand slam home runs. I have never seen one, but I recall reading about George Freese’s 1955 homer in Baseball Digest. The writer described an inside-the-park grand slam as the most exciting play in baseball, and while I don’t go in much for hyperbole, I can understand why he would say that. It must seem to the fans as if the earth has stopped turning its axis while they hold their collective breath and watch that ball and the batter racing for the plate.

For many years after George Freese ran his home run home, I thought of his feat as unusual. Certainly, in decades of watching baseball, I had never seen anything like it. But I have learned since that there have been far more such homers than I would have imagined. Even Yankee pitcher Mel Stottlemyre hit one — in 1965. Some players have hit more than one, and some players have hit more than one in one season — for example, third baseman Joe Judge, who did it twice in 1925.

For many years after George Freese ran his home run home, I thought of his feat as unusual. Certainly, in decades of watching baseball, I had never seen anything like it. But I have learned since that there have been far more such homers than I would have imagined. Even Yankee pitcher Mel Stottlemyre hit one — in 1965. Some players have hit more than one, and some players have hit more than one in one season — for example, third baseman Joe Judge, who did it twice in 1925.

Many of the inside-the-park grand slams were hit during the dead-ball era, and the first one was hit by Harry Stovey of the Worcester Ruby Legs in 1881. Stovey did it again in 1886. It was appropriate in a way that he was the first to turn this trick, because he was the pre-eminent home run hitter of his day and the first player to hit 100 home runs in his career.

Netflix Update No. 54: “Sunflower”

October 22, 2011

Having dabbled with Marcello Mastroianni in Macaroni and Marriage Italian Style, we went to the well once more in the form Sunflower, a film we had never heard of. The results were mixed.

Having dabbled with Marcello Mastroianni in Macaroni and Marriage Italian Style, we went to the well once more in the form Sunflower, a film we had never heard of. The results were mixed.

This film, made in 1970, was the last directed by Vittorio De Sica, and —significantly — it was the first western film shot, in part, in the Soviet Union. Mastroianni, who was 46 when this movie was made, plays Antonio, a happy-go-lucky Neapolitan who is drafted into the Italian army during World War II. He is not a willing conscript, and his valor isn’t helped by the fact that he is in the middle of passionate fling with Giovanna, played by 36-year-old Sophia Loren. His attempt, with Giovanna’s connivance, to avoid military service results in a court-martial and his deployment to the Russian front — which was a brutal fate thanks to both the Red Army and the merciless winters.

When the war ends, Antonio doesn’t return, but Giovanna is convinced that he is still alive. After failing to get any satisfaction from public authorities, she travels to Russia to look for him. It’s not a spoiler to say she finds him, inasmuch as Mastroianni is the co-star. Some may find the circumstances and outcome predictable; some may not.

Watching this film, which has Italian dialogue and English subtitles, is an uneven experience. Mastroianni and Loren are an irresistible combination, and they play their parts well, but the story itself is at times melodramatic and implausible. In what seems to have been an overreaching attempt to project the character’s moods, Loren is made to look at times as if she’s 30 and at other times as if she’s 50.

Watching this film, which has Italian dialogue and English subtitles, is an uneven experience. Mastroianni and Loren are an irresistible combination, and they play their parts well, but the story itself is at times melodramatic and implausible. In what seems to have been an overreaching attempt to project the character’s moods, Loren is made to look at times as if she’s 30 and at other times as if she’s 50.

The photography in both Italy and Russia is eye-catching, and there is a very effective scene in which Giovanna visits a Russian hillside that is dotted with hundreds of wooden crosses marking the graves of Italian soldiers. The film also has a wonderful score by Henry Mancini that was nominated for an Oscar.

Netflix Update No. 53: “Marriage Italian Style”

October 10, 2011

When we recommended to a neighbor that she watch the Marcello Mastroianni-Jack Lemmon film “Macaroni,” she countered by referring us to the 1964 movie “Marriage Italian Style,” in which Mastroianni stars with Sophia Loren. I had seen it about 40 years ago, but didn’t remember anything about it.

When we recommended to a neighbor that she watch the Marcello Mastroianni-Jack Lemmon film “Macaroni,” she countered by referring us to the 1964 movie “Marriage Italian Style,” in which Mastroianni stars with Sophia Loren. I had seen it about 40 years ago, but didn’t remember anything about it.

Filmed in Italian in Naples, this is the story of an amoral businessman who meets a teen-aged prostitute in a brothel during an Allied bombing raid, and then makes her his mistress when they meet again several years later. Domenico Soriano (Mastroianni) is in the baking business, and he puts Filumina Maturano (Loren) in charge of one of his stores while he keeps her — outside his home — in a very comfortable style. Filumena is not satisfied with this arrangement and she pressures “Dummi,” as she calls him, both to publicly acknowledge her and to make her a part of his household. Step-by-step she gains concessions that include a room in his house and recognition as the “lady” of the premises, but she does not get the final prize, marriage, until she employs a subterfuge that blows up in her face.

Domenico’s passion for Filumena degrades into disgust, and he takes up a relationship with a young cashier at one of his shops.

Domenico’s passion for Filumena degrades into disgust, and he takes up a relationship with a young cashier at one of his shops.

Meanwhile, Filumena has a secret of her own — actually, three — namely a trio of sons she has borne as a result of her career, one of them by the unwitting Domenico.

This film, directed by Vittorio De Sica and filmed in the earthy Neapolitan environment, is a combination of farce, tawdry melodrama, and implausible plot, that can’t be taken seriously. Considering the lengths De Sica went to in order to exploit Loren’s legendary physique – as opposed to the weight of her acting – the Oscar she won as “best actress in a foreign film” seems farcical in itself.

This film, directed by Vittorio De Sica and filmed in the earthy Neapolitan environment, is a combination of farce, tawdry melodrama, and implausible plot, that can’t be taken seriously. Considering the lengths De Sica went to in order to exploit Loren’s legendary physique – as opposed to the weight of her acting – the Oscar she won as “best actress in a foreign film” seems farcical in itself.

Having said that, I can report that the movie, taken for what it is, is funny and entertaining. The surroundings, whether indoor or out, are engaging, and Mastroianni himself is hard to completely dislike in any role. In this case, except for the ludicrous conclusion, he is worth watching as the rake trying to avoid the consequences of a misspent adulthood.